Mahsa Alimardani imagines playing Pokémon Go in Tehran, holding the game up to a picture of Azadi Tower.

Animated creatures known as Pokémon began to invade the imaginations and mobile phones of people around the world in July 2016, when augmented reality game Pokémon Go was released in select countries.

The record-breaking game requires players to walk around, using Google Maps data and their smartphone’s camera to superimpose characters into their everyday surroundings. Players can then try to capture any Pokémon they come across by swiping on their phone's screen.

After the game's release, crowds of people were suddenly crawling public places, phone in hand, in pursuit of Pokémon — to the amusement or annoyance of non-players.

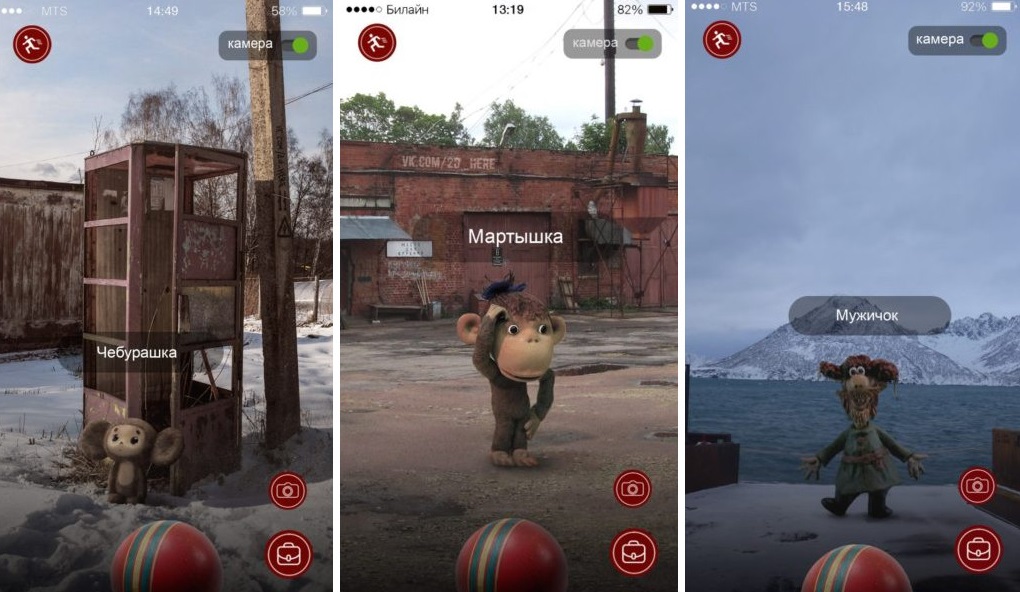

The lengths to which some players have gone, such as hiring motorcycle taxi drivers to cover more ground in Peru, have made for amusing media coverage of the Pokémon Go phenomenon. Other creative fans have given the game a unique twist, such as a group of Russian artists and designers who reimagined Pokémon Go with characters from old Soviet cartoons.

From left to right: Everyone's favorite big-eared wonder Cheburashka; the Monkey from 38 Parrots cartoon; and The Dude (Muzhychok), a character from the great plasticine cartoon “Last Year's Snow Was Falling.” Images from 2D Among Us.

But the game has also touched on some serious issues like politics, international relations, censorship and religion in countries like Iran, Japan, China and Russia.

Months after its release elsewhere in the world, Pokémon Go remained technically unavailable in China, which heavily censors mobile apps and games. Nevertheless, eager players found ways to climb the Great Firewall to access the game, such as spoofing their GPS locations in order to virtually show up in countries where the game was live.

The sudden appearance of Chinese players outside of China hasn't gone unnoticed. In Japan, a Pokémon “gym” located at Yasukuni Shrine, which is devoted in part to memorializing the country's World War II dead, was taken over at one point by a Pokémon named “Long Live China!” — a poke in the eye to Japan, which doesn't have the friendliest of relationships with China.

For Chinese players, there's also the risk of being labeled a traitor for playing the game. Nationalistic sentiment has grown in recent years in China, and as a consequence Japan and the US — and by extension any products or businesses associated with them — have often been singled out as enemies. For its part, Pokémon Go was developed by US-based Niantic Labs in partnership with Japan-based Nintendo, two possible strikes against it when considered through the lens of extreme Chinese patriotism.

A VPN (aka virtual private network) is a tool that lets you create a secure connection to another network in a different physical location. So someone in Iran, for example, might connect to a VPN located in Canada. This allows them to bypass Iranian censors and use the Internet as if they were in Canada. It's an important tool for people who live in countries whose governments restrict access to certain websites and services.

In Iran, authorities banned Pokémon Go, citing security concerns. Earlier, the head of the country's computer games authority said he had spoken with the game's developers, demanding that they host their data servers inside of Iran and they cooperate with the government to prohibit Pokémon Go from targeting sensitive locations. Like in China, people still found ways to get their hands on the game, such as using a VPN to download it. However, players reported not finding many Pokémon in major cities like Tehran.

Global Voices editors Oiwan Lam, Mahsa Alimardani and Nevin Thompson explored these instances of censorship and politics in-depth in an episode of The Week That Was at Global Voices podcast:

Government ministers in Egypt, Kuwait and United Arab Emirates issued stern warnings about gamers approaching or photographing buildings that are significant to state security. Kuwait interior ministry undersecretary Suleiman al-Fahd said in a statement that the ministry “informed security men to show zero tolerance to anyone approaching such prohibited sites, deliberately or not.”

And in Russia, a young video-blogger named Ruslan Sokolovsky was jailed after playing Pokémon Go inside a Russian Orthodox cathedral. Police are investigating him for committing extremism and offending religious people, and if convicted, he could go to prison for up to five years.

The video of him playing inside the Church of All Saints has nearly 1.2 million views on YouTube, and the case has drawn comparisons to Pussy Riot, a punk rock group that staged a performance in a Moscow cathedral in 2011 to protest against Orthodox Church leaders’ support for Russian President Vladimir Putin. Three Pussy Riot members were eventually tried and convicted of “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred,” and two served time in prison.

Want to read more of our Pokémon Go coverage?

Check out the full list of Global Voices’ stories on the subject below.

-

Russia's Pokemon-Go-Playing Atheist Outlaw Has Some Powerful Enemies (8 September 2016)

-

Russia's Pokemon Gulag (5 September 2016)

-

Peruvian Pokémon Go Players Eager to Cover More Ground Are Hiring Motorcycle Taxi Drivers (23 August 2016)

-

Netizen Report: In China and the Middle East, Pokémon GO is Not All Fun and Games (4 August 2016)

-

The Week That Was at Global Voices: Pokémon Go Gets Political (1 August 2016)

-

Playing Pokémon Go in China Is Not Easy, but Many Are Still Risking It (27 July 2016)

-

With Trepidation and Excitement, Pokémon Go Finally Launched in Japan (25 July 2016)

-

PokéStops or Stopping Poké? Iran Reacts to the Pokémon Go Phenomenon (20 July 2016)

-

Russian Artists Reimagine Pokémon Go With Soviet Cartoon Characters (18 July 2016)