From left to right: Kundera's work in Turkish, the first Kundera's biography in Czech by Jan Novák, and Kundera's work in Chinese. Photo by Filip Noubel, used with permission

At 91, Czech-French author Milan Kundera enjoys cult status among millions of readers around the globe. But in the Czech Republic, the author is mostly ignored, often accused of scorning his home country, and of having collaborated with the communist-era State Security. His first and non-authorized Czech biography was just released in Czech in late June, relaunching a national debate about his controversial persona.

The myth of Milan Kundera

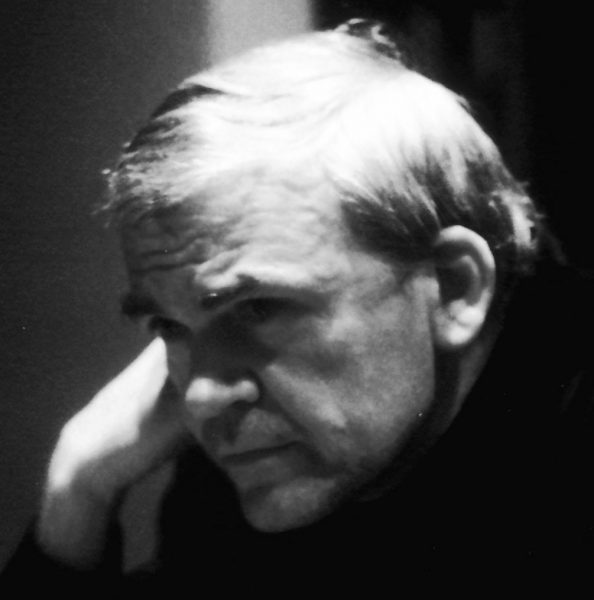

Portrait of Milan Kundera by Elisa Cabot is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Milan Kundera is often described as being the 20th century Central European writer par excellence: he grew up in Czechoslovakia, experienced WWII, joined the Communist Party, studied literature and cinema, endorsed communist ideology but later became disillusioned with it, and eventually fled to France — a country of which he became a citizen in 1981.

His works include 10 novels, a collection of short stories, four plays and many essays, as well as poetry. While he started writing in Czech, he gradually shifted to French in his exile, and considers himself a French author now.

Kundera's ascension in the West was stellar: in a Literary Review issue of 1985, novelist and literary critic Olga Carlisle didn't hesitate to write:

In the 1980s, Milan Kundera has done for his native Czechoslovakia what Gabriel Garcia Márquez did for Latin America in the 1960s and Solzhenitsyn did for Russia in the 1970s. He has brought Eastern Europe to the attention of the Western reading public, and he has done so with insights that are universal in their appeal.

One of his most famous novels “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” (Nesnesitelná lehkost bytí) talks about a womanizer and his many love-stories, and is a reflection on relationships and eroticism. It also mentions the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia by Soviet troops, after which Kundera left his country, and sought asylum in France in 1975.

The book was made into a film in 1988 by US director Philip Kaufman, further propeling Kundera towards global fame:

Kundera reached a global audience through countless translations in over 40 languages, and he is mentioned by many successful authors as an inspiration for their work. He has also been nominated for many years as a Nobel Prize candidate in literature.

But there is one country where Kundera is far from recognized as a key literary figure: the Czech Republic

No one is a prophet in his country

From the moment he started writing in French in 1975, Kundera distanced himself from Czechoslovakia. And while most Czech exile writers returned — at least to visit when Communism ended in 1989 — Kundera waited until 1996 to pay his visit.

Since then he has always visited the country incognito, and is known for refusing media interviews. He also blocked or delayed the publication of his books in Czech. His famous novel “Life is Elsewhere” was first published in Czech in 2016, 43 years after it was published in France.

Jean-Dominique Birerre, author of his first biography in French published in 2019, explains in an interview he gave to Czech Radio Prague International in May 2019 how most Czechs view Kundera:

J’ai l’impression qu’une partie des Tchèques, des intellectuels entre autres, lui reprochent premièrement son passé communiste et deuxièmement, le fait d’être complètement invisible même après la révolution de Velours : de ne participer à rien…alors qu’il aurait pu être un grand homme dans son pays.

I am under the impression that some Czech people, including intellectuals, blame him first for his communist past, and secondly for being completely invisible even after the Velvet Revolution: that he did not take part in anything…even though he could have been an important figure in his country.

Kundera's statements and attitude have reinforced the stereotype shared by many in the Czech Republic that exiles “had it easy” as they did not have to endure the years of censorship, lack of basic goods, travel bans under communism.

But the major blow to Kundera's image in the Czech Republic came in November 2008 when the most influential weekly Respekt came up with a rather sensational but well researched article saying it had proof that Kundera cooperated with the Czechoslovak State Security, reporting on critics of the regime.

The news created an international scandal, with several Nobel Prize-winners denouncing the article as a hate campaign against Kundera, who denied the accusations but refused to provide explanations, and elected not to sue the media outlet.

Witch-hunt phase two?

The past two years have reignited the debate around Kundera. In late 2019, Kundera invited to his Paris flat the Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, who is widely regarded as a corrupt figure under investigation for years by the European Union on accusations of conflict of interest and embezzlement of European funds.

Soon after this visit, Kundera was given Czech citizenship, having lost his former Czechoslovak citizenship in 1979 by orders of communist authorities in Prague.

While most people would agree Kundera deserves to obtain a Czech passport, the conditions under which it was achieved struck another blow to his public image in the country, since Babiš is believed to have been an agent of Czechoslovak State Security.

Jsem rád, že jsem to před rokem inicioval a vážím si toho, že jsem mohl ??https://t.co/RthCcUVUnX

— Andrej Babiš (@AndrejBabis) December 3, 2019

I am glad that I initiated this [giving Czech citizenship to Kundera] a year ago, and I value the fact that I was able to do it.

The publication in June 26 of his first biography in Czech, written by by Jan Novák and called “Kundera Český život a doba” (Kundera: A Czech Life During that Period) covers the writer's life up to 1975 when he was still living in Czechoslovakia. Understandably, the book is a sensation. Book reviewers, literary critics and the media have already weighed in on its controversies.

Novák, who himself lived in exile in Chicago for many years, and spent four years researching his book, gave a 25 minute long video interview to the Internet TV channel DVTV on June 26, in which he accuses Kundera of “lying about his biography” and making himself a “victim” when he was actually a beneficiary of the Communist system. Novák never met with Kundera during his work on the book.

Kundera never denied he believed in Communism: in 1954, he wrote a long poem, “Poslední Máj” (The Last May) praising Communist hero Julius Fučík. In 1963, he was also awarded the Klement Gottwald State Award for his play “The Owner of the Keys” (Majitelé klíčů). Back then, only the most loyal artists were selected for this supreme prize. But Kundera has since distanced himself from those works, and does not mention them in his list of published books.

Pavel Kosatík, a major essayist and expert on Czech identity, reacted to Novák's book on June 17 on Facebook:

Z víceméně stejných zdrojů jsem vyčetl něco úplně jiného než Novák, což je normální, ale proč musí mít černobílý hnojomet 900 stran, jsem nepochopil. Ta kniha je tou monotónností až komická: kdykoli se má nějak vysvětlit nějaký další Kunderův čin, Novák vybere vysvětlení padoušské. Když mě někdo štve (protože tohle je téma Novákovy knihy), proč to nestačí říct jednou větou?.Proč hned tzv. literatura.

I read pretty much the same sources but my conclusion is very different from the one reached by Novák, which is normal, but I don't understand why this thrashing needs to be 900-pages long. This book is so monotonous it becomes comical: whenever he needs to explain an act by Kundera, Novák chooses to paint him as a villain. When I am angry at someone (because this is the topic of Novák's book), isn't one sentence enough to say it? Why write a so-called book.

In the Týdeník Echo Ondřej Štindl wrote a long article “Další kolo bitvy o Kunderu” (Next round in the Battle of Kundera):

Optimista může chovat naději, že jednou zdejší debata o Milanu Kunderovi překoná tu mnoho let trvající neurotickou fázi. Také je možné, že čas střetů a slovních válek vystřídá doba zapomnění a lhostejnosti. Bylo by to hořké a groteskní, svým způsobem i docela kunderovské.

An optimist can still hope that there will be a time when the debate around Milan Kundera will overcome its long-lasting neurotic phase. It is also possible, that the time of clashes and wars of words will be followed by a time of forgetting and indifference. This would be bitter and grotesque, thus in its own way, very Kundera-like.