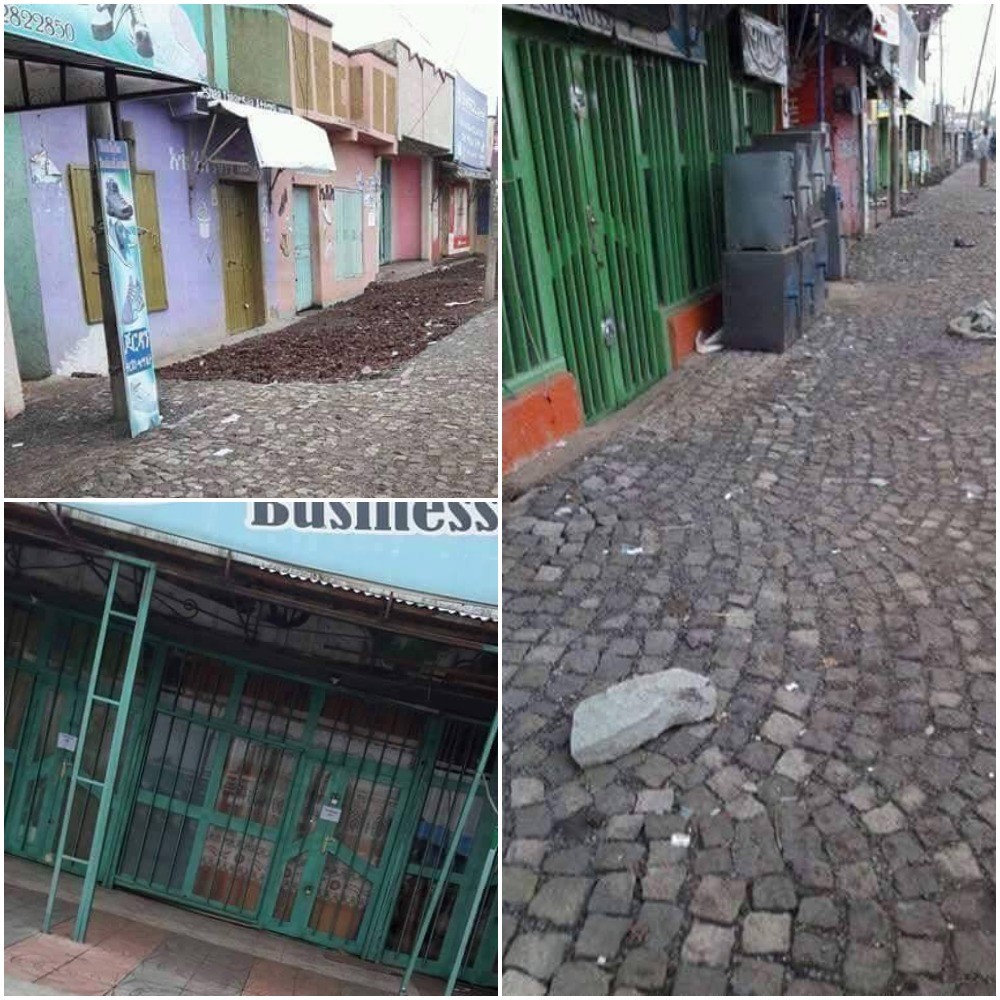

Closed shops and deserted streets in Bale Robe, a town in Eastern Ethiopia. Photo sourced from Jawar Mohammed's Facebook page and widely shared on social media.

The Oromos, Ethiopia’s single largest ethnic group, collectively rallied against Ethiopia's ruling regime on Wednesday, August 23, this time by staying at home, skipping work and refusing to open their businesses.

The towns and cities of Oromia, Ethiopia’s largest administrative region where the Oromo people are concentrated, are normally bustling. But photos shared on Facebook showed shopping centers and open markets were largely quiet on Wednesday and Thursday. Roads were nearly empty, and public transportation services providers such as buses stopped, forcing government workers who had no other way of reaching their post to take part in the protest.

#Breaking: Harar and its surroundings under strike; no trade and transport activities observed. Some damaged vehicles were also spotted. pic.twitter.com/YmyOSIt2Tk

— The Reporter (@TheReporterET) August 24, 2017

The strike, which is set to last for five days, was called by a mysterious Oromo youth movement calling themselves “Qeerroo,” referring to their youthfulness in the Oromo language.

The secretive activist group’s main demand is the release of political prisoners and jailed activists, in particular prominent opposition figures such as Merera Gudina and Bekele Gerba who were arrested over the last two years of protests and charged with crimes such as terrorism and promoting “regime change using illegal forceful means and threats”.

Two years ago, thousands across Ethiopia mainly in the Oromia and Amhara regions rose up, demanding more political freedoms and social equality and a stop to government land grabs. In terms of representation, Oromos make up 35 percent of the country’s 100 million people and Amharas account for about 30 percent of the population. The Tigrayans, on the other hand, represent only 6 percent of the population, yet Tigrayan elites are among the most high-ranking military officers who control the nation's security.

The government's response to that uprising was brutal; hundreds were killed and thousands arrested. In October 2016, authorities declared a nationwide, nine-month state of emergency that was lifted on August 4, 2017.

With this recent strike, the Qeerroo also want an end to what diaspora-based activists say an unjust tax hike. In July 2017, the government introduced a new tax scheme for small business operators across the country that prompted a similar protest both in the Oromia and Amhara regions. That protest in July quelled without any demonstrable political results, but the demand has resurfaced here.

Also, in the middle of all of this, the Oromos have a border dispute with the neighboring Ethiopian Somali. In April 2017, during the state of emergency, the Ethiopian government told the two regions to come to an agreement redistricting their boundaries per the outcome of a referendum that was conducted 10 years ago, in which Oromia lost some land. The government recruited “Liyou Police” or special police of the Somali region as an armed force to enforce the outcome.

The Oromos saw this as a plot of the Tigryan elite to weaken them, and they accuse Liyou Police of human rights violations. Ending the alleged human rights violations is contained within demands of the ongoing peaceful protest.

#Ethiopia – call for an end to “Liyu police anarchy” in #Oromia as stay-at-home strike spreads through the region https://t.co/GbY1YcRhz0 pic.twitter.com/BNnsZ0gnQA

— Addis Standard (@addisstandard) August 24, 2017

‘It should be waged at a national scale’

The Qeerroo reach to their audience entirely through Facebook, a website, and diaspora-based satellite television networks. Jawar Mohammed, executive director of Oromo Media Network, appears to be a major source of information. His Facebook page has more than one million followers, most of them gathered over the last three years.

The only apparent major information hub focusing on the current protest is the Facebook page of America based Oromo activist Jawar Mohammed.

— Zecharias Zelalem (@ZekuZelalem) August 23, 2017

The ongoing protest underscores the rise of a potentially treacherous challenge to the ruling Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) monopoly of power: widespread public outrage and a growing willingness of the public to participate in a strike when they are called.

But there are concerns about the absence of a single compelling protest message, coming even from supporters of the cause.

The protest message is fairly written in Oromo language, primarily focused on mobilizing people who dwell in the region. Urging his compatriots to expand the protest into other parts of the country, Abebe Gellaw wrote on Facebook:

We cannot wage effective and sustained civil resistance at a regional level as the cost would be too high on the people without the desired outcome. The cost should rather be unbearable to the regime, not the people. It should be waged at a national scale in a manner that can overwhelm and stress out the controlling power of the regime.

Furthermore, on August 22, as the protest was set to begin, activists put out communications directed at a range of demographic groups in Oromia who are not willing to participate that came off as a threat of violence, particularly against the Guraghe ethnic minority who live intermingled in towns and cities across Oromia.

Though activists insist that their message is nonviolent and that they harbor no hatred for other peoples, this may prove a test for the Qeerroo to figure out how to address their anger against the ruling EPRDF without inciting violence.

Diaspora-based activists have declared the action so far a success and urged participants to continue. It remains to be seen what political impact the protest has.