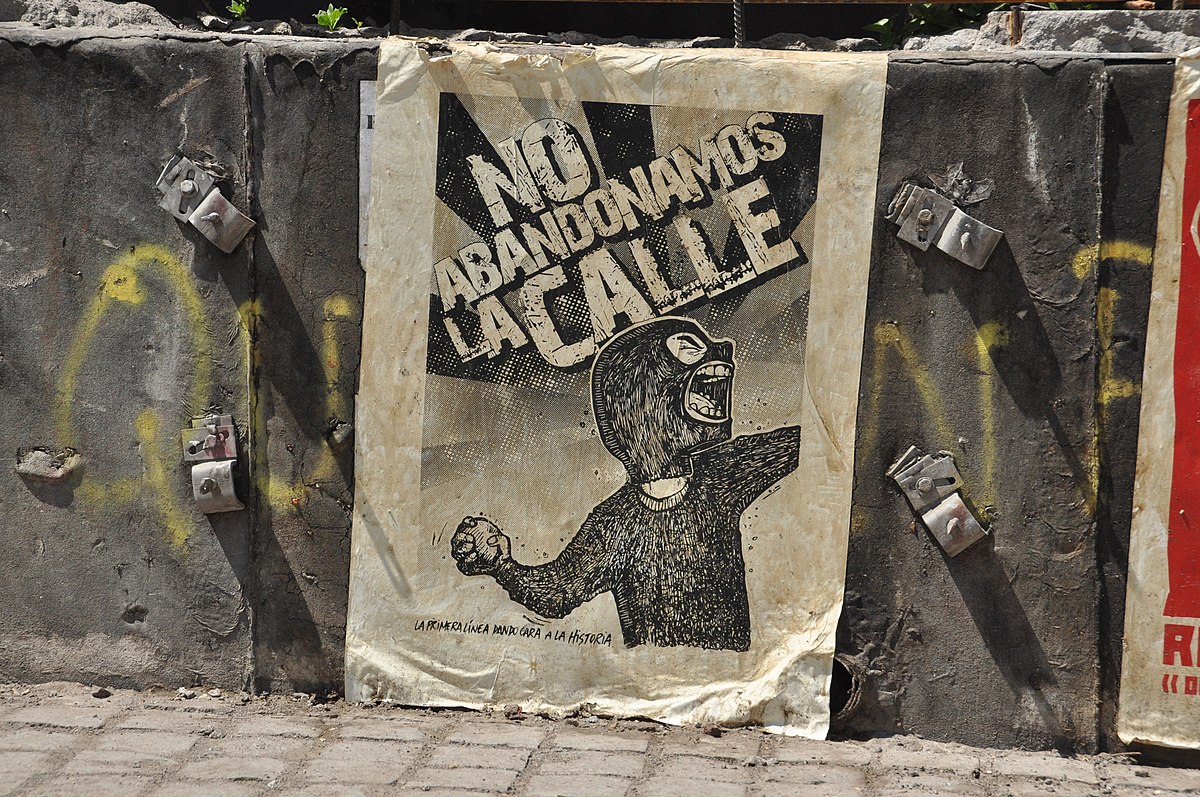

Street art in Santiago, Chile, created after the social uprising of October 2019. It reads “We will not give up on the streets (protests)”. Photo from Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED.

On September 11 this year, during the 50th anniversary of the coup d'état against socialist president Salvador Allende, thousands of Chileans marched to remember the more than 40,000 victims who were detained, disappeared, tortured, and executed during the 17 years of Augusto Pinochet's dictatorship. Pinochet implemented a repressive state policy, resorting to human rights violations through existing state bodies and others created solely for that purpose.

What started out as a peaceful protest culminated, however, in a series of clashes between demonstrators and the security forces in the capital Santiago. There, several individuals threw stones at the Palacio de la Moneda, the seat of the Chilean government, smashed the security barriers, and destroyed access to a cultural center located in the building. Tensions are evident in a country that many experts describe as fractured, divided, and polarized.

What happened during this commemoration inevitably mirrors another unfortunate episode in the country's history: the social uprising of 2019 that highlighted the deep socio-political problems that persist in Chile. On October 14, 2019, high school and university students gathered to dodge the Santiago subway fare as a protest against the increase in ticket prices in one of the countries with the highest cost of living in the region. But this was only the tip of the iceberg.

As Chilean journalist Nicolás Lazo Jerez points out:

Con el curso de las horas, quedó claro que el movimiento respondía a otros factores además de esta medida puntual porque aparecieron otra serie de demandas que reflejaban un sentimiento de descontento más profundo frente a las políticas de gobierno de los últimos treinta años. Parte de lo que motivó las protestas tiene que ver con la contradicción de hecha por los gobiernos de centro izquierda en 1990 de resolver deudas históricas respecto a la desigualdad con lo que efectivamente sucedió a lo largo de los años. Aunque algunas promesas fueron cumplidas, principalmente en materia de cobertura, los altos índices de desigualdad no solo no fueron resueltos, sino que se han profundizado.

As time passed, it became evident that the protest movement was driven by more than just this particular measure, as a new set of demands emerged, reflecting a deeper discontent with government policies over the past thirty years. Protests were partly motivated by the inconsistency of center-left governments in the 1990s in addressing historical inequality issues compared to the actual developments over the years. Although some promises were fulfilled, mainly in terms of social coverage, the high rates of inequality have not only not been solved, but have deepened.

All this then triggered a series of mass protests, which provoked a wave of public disorder and violence throughout the country, forcing then President Sebastián Piñera to declare a State of Emergency and a curfew.

The 2019 social uprising was also marked by serious human rights violations against protesters, including authorities’ abuses against protesters, arbitrary arrests, and various cases of police violence including eye trauma and mutilations. As documented by Amnesty International, an estimated 8,000 people were victims of excessive use of state force.

One of the most emblematic cases is that of the now-senator Fabiola Campillai, a symbolic figure of the protests, who lost her eyesight and sense of smell due to the use of pellets by the carabineros. Although the perpetrator was convicted, as Lazo Jerez points out, “there are many other cases that remain unpunished.”

Currently, 46 percent of these cases have been archived due to lack of evidence. The situation has not improved in the following years, despite the commitments made by President Gabriel Boric's government to solve the structural problems of the Chilean socioeconomic system and move towards social equality, as well as the urgent calls to carry out a police reform.

For example, a National Public Opinion Survey conducted in November 2022 indicated that 64 percent of those surveyed perceive the political situation as bad or very bad and 55 percent indicate that Chile is ”stagnant.” Similarly, another series of protests have taken place in different cities of the country, such as the ”mochilazo estudiantil” (student protests) in March 2023 to demand better educational conditions.

All in all, past and current events in Chile seem to have something in common: the impunity that permeates the systematic human rights violations and the lack of guarantees to the victims. This is especially true in terms of transitional justice, such as the clarification of the abuses committed during the dictatorship and the social uprising and reparation measures for these serious atrocities. The search for justice and truth continues to be a very sensitive issue for the country, where some sectors have begun to justify the repression that occurred during the military regime.

A comprehensive Agenda for Truth, Justice, and Reparations for victims who suffered human rights violations was created to make progress in the reparation of victims after the 2019 protests. There is also a plan to determine the whereabouts of many people who disappeared during the military coup, which has made significant progress, but which, according to several human rights organizations representing victims, has not been effective enough in achieving its mandate.

Chile still has important debts to settle with the past, and it must also focus on resolving growing social demands. At this point, it is necessary to ask, if the past of the dictatorship has not been resolved, how can we be sure that the victims of the social uprising will not suffer the same fate? Although the answers are not simple, for some Chileans the chances to reflect on lessons learned and proposals for the future seem distant.

Lazo Jerez concludes:

Los esfuerzos para ejecutar un plan de rendición de cuentas por lo ocurrido durante el estallido social son bastante recientes; si aún no se pueden poner de acuerdo sobre algunas verdades sobre la dictadura que fue hace 50 años, qué puede esperarse del estallido. No existe demasiada voluntad política, entre otras razones porque un panorama con un fuerte reflujo conservador. Todas estas causas están muy postergadas, y ello también permea en el asunto relativo a la dictadura.

The efforts to carry out a plan of accountability for what happened during the social uprising are quite recent; if they still cannot agree on some truths about the dictatorship that was 50 years ago, what can be expected for the uprising. There is not much political will, among other reasons because of a panorama with a strong conservative backlash. All these matters are long overdue, and this also affects the question of the dictatorship.