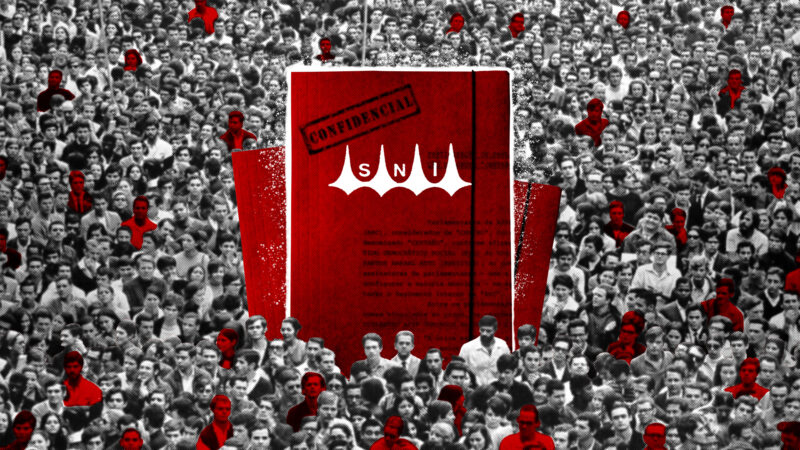

Image by Matheus Pigozzi/Agência Pública, used with permission.

This text, written by Lucas Pedretti and edited by Thiago Domenici, was originally published on Agência Pública's website on March 27, 2024. An edited version is republished on Global Voices under a partnership agreement.

In the early days of March 1985, shortly before José Sarney assumed the presidency, the National Information Service (SNI) produced a secret study, which compared the performance of intelligence agencies in democracies and in totalitarian regimes, with the title “Information in democratic regimes.”

In its assessment, employing “certain methods” in democracies could represent “violations of individual rights and committing abusive acts.” In addition, the document said that investigations would be “subject to a more liberal public opinion and legislation, making it difficult to draw a line where the “legitimate aspirations of the State end and citizens’ right to privacy begin.”

The document also assesses that, in the absence of public opinion and opposition political parties, intelligence services in totalitarian regimes could act without any “ethical embarrassment” or “legal impediment.” It concludes: ”This is the key element that differentiates intelligence services around the world.”

This is a report on a set of unpublished documents found in the SNI archives by Agência Pública, guarded today in the National Archives (Arquivo Nacional). They reveal how the agency manoeuvred politically, aiming to continue its spying activities, even after the departure of the last dictator-general as president.

The birth of the ‘monster’

Created immediately after the 1964 coup d'état which led to 21 years of dictatorship in Brazil, the SNI quickly became the centre of a complex repressive apparatus put in place by the military. Established by Law No. 4,341 on June 13, 1964, the legally defined purpose of the agency was to “advise the President of the Republic” regarding information and counter-information activities.” In practice, SNI agents carried out all kinds of activities linked to political repression, participating in street operations and torture.

The institution was created by General Golbery do Couto e Silva, one of the main figures in the coup.

The historian Priscila Brandão, author of the book “SNI and Abin: A Reading of Brazilian Secret Services Throughout the Twentieth Century,” explains that the body expanded rapidly after its creation. “The SNI, like an octopus, spread throughout the State. Where it thought it needed to, it created a new agency, ” she explained.

Soon, the agency had a presence in civilian ministries, universities, and public companies and coordinated with the intelligence services of the three armed forces, the National Security Council, and the state-level security secretariats.

This set of agencies dedicated to spying and repression constituted a wide-reaching and autonomous network of arapongagem (spying). With this, the regime was able to intensively monitor any movements seen by the military as a threat to national security. As the National Security Doctrine, the military regime's ideological underpinning, was based on a paranoid and authoritarian worldview, this meant that, in practice, virtually all sectors of society were the target of some type of spying during this period (1964–1985).

One study carried out by experts of the National Archive of Brasilia in 2008 counted over 300,000 Brazilians monitored by the SNI during the dictatorship, many of whom were arrested, tortured, and murdered.

With the end of the regime in 1985, the question of what to do with the organization arose. Golbery himself observed: ”I created a monster.” This change made clear the difficulties that a democratic system would have in dismantling such a powerful apparatus, holding sensitive data on all the political leaders of the period.

SNI tried to survive

In the report “The Media’s Main Approaches to the National Information Service,” the SNI appeared irritated by the criticism that was mounting in the national press over its fate. Speaking bluntly, the report observed that “it was created under a regime of censorship that lasted until 1977, sheltering it from public criticism.” According to another excerpt, “the intense criticism” that was “expressed through the media” caused “very deep discontent to the members of the SNI.”

The document highlights the strategy that the SNI then planned to use: “a change of public image.” The report shows that the spies’ choice was not to start acting within the framework of the rule of law but to find ways to ensure that their “public image” was not tarnished.

During this period of re-democratization, the prevailing idea was that the end of the dictatorship should be managed without “breaks” in the status quo. At the time, a “reconciliation” characterized by “forgetting” and without looking to revenge was put forward as a way of dealing with the crimes and atrocities committed by the military regime.

Throughout the re-democratization process, and already under a civilian government, the SNI acted to “neutralize” what it considered threats to its image. These would become more intense during the period of the National Constituent Assembly (ANC), held to create a new Constitution.

Lobbying for re-democratization

Among the documents retrieved by Pública are reports that prove how the SNI actively sought out parliamentarians who were part of the Constituent Assembly in order to present legislative proposals to be included in the new constitution (1988). The parliamentarians themselves were spied on by the SNI.

Priscila Brandão explained that, when the Constituent Assembly’s work was in the phase of thematic commissions, the group responsible for discussing intelligence and defence issues was under the command of Congressman Ricardo Fiúza, who was close to the military. “Nothing that was proposed which was not in their interest was approved,” she noted.

There was another battlefront: the group that discussed fundamental rights. The Committee on Sovereignty and the Rights of Men and Women discussed the articles aiming to guarantee the right to privacy, the secrecy of correspondence, and “habeas data,” which works so that every citizen can request the information that public entities hold about them.

In June 1987, the SNI produced a first report similar to an internal study. In it, each of these articles was analyzed, and the agents presented different suggestions in order of priority.

This study was followed by the implementation of a lobbying strategy and political action by the agency, to try to protect its interests.

In August of that year, the Constituent Assembly was already at a later stage. A review commission was underway, aiming to present the first draft text for the new constitution. The SNI then produced a new report detailing the lobbying it had organized.

According to the document, “during the phase of submitting amendments to the preliminary draft by the review commission,” the agency “initiated contacts with various senators and federal deputies, with a view to defending the interests inherent to its activities.”

It details that 101 amendments were presented by 13 members, seeking to remove or amend 12 provisions of the text. The document concludes that “as a key achievement in the rapporteur's replacement [text], satisfactory results were obtained in 8 provisions.”

Even so, the SNI still remained active in the following stages of the Constituent Assembly.

At the turn of the year, an important change occurred in the Constituent Assembly: the emergence of the multi-party bloc called Centrão (“Big centre”). The group aimed to block what the more conservative parliamentarians saw as liberalizing excesses in the text that had then been drawn up.

Like the armed forces, SNI saw Centrão as an ally. Viewing the political left as its main adversary, the agency began to coordinate directly with the group. This is what was revealed in another report from January 1988, after the bloc's formation.

Although the new constitution included some of the elements that the SNI had wanted to block, the agency survived the regime change. “We went through a political transition, and the civilian power was not able to take on the military power to the point of putting an end to the SNI,” Brandão explained.

Its termination would come about only in 1990, in the early days of Fernando Collor de Mello's government, the first president elected by popular vote after the military dictatorship.

“Not necessarily because Collor had any big projects for intelligence activities,” the historian noted. “When Collor was a candidate, the then head of the SNI left him waiting for five hours. So his inclination to put an end to the SNI was linked to a personal vendetta.”

The creation of a new intelligence agency also did not benefit from deep discussion. ”The Brazilian Intelligence Agency (Abin) was created in 1999 as a result of a very poor [quality] congressional debate,” Brandão explained.

Initially, Fernando Henrique Cardoso's government sought to establish the agency through a provisional measure. Faced with criticism from Congress, he introduced full legislation in 1997. “But there was very little debate before getting to the final wording of the bill,” she recalled.

The result was legislation assessed to be “very poor” by the expert, as it worked with an “extremely broad” concept of what intelligence activity is, which would leave the risk of distortions in the agency's role. Brandão also explained that, to this day, the doctrine that the agency follows is influenced by the terms of the National Security Doctrine left by the dictatorship.

“So that's the big problem. There is a perception of the individual, of the Brazilian citizen as an enemy, as someone who may have their rights disrespected,” the historian noted.