Children at play in an informal tented settlement in Jordan. PHOTO: Noon Arabia

Imagine waking up without your bed, finding yourself sleeping on the floor instead. Imagine if there was no ceiling or concrete walls to shelter you, only a tent or a caravan if you are fortunate. Imagine having lost everything you own, including all or some of your family, relatives or friends. This is what millions of Syrians have experienced since the uprising began in their country in March 2011. Syrians, who lost their homes and means of livelihood, were forced to flee the war in their homeland crossing into neighbouring countries to seek safety and shelter and have since become refugees.

Three friends and I travelled to Jordan on the first week of November 2015 to work as volunteers supporting Syrian refugees, and to witness first-hand the conditions in which they live.

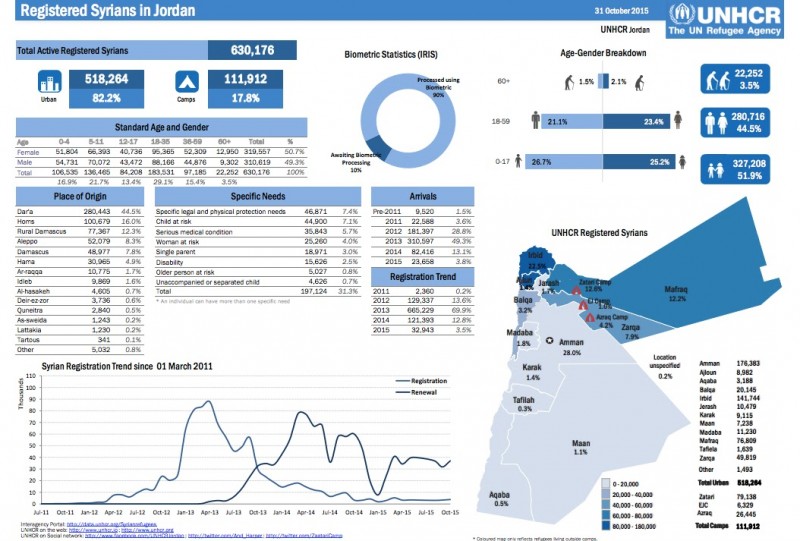

According to Amnesty International, more than 4 million refugees from Syria (95 per cent) are in just five countries: Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt. Jordan hosts about 650,000 of them, which amounts to about 10 per cent of the country's total population. This is in addition to the large numbers of refugees from Palestine and Iraq Jordan has been hosting over the past several years, despite its own socio-economic challenges.

Approximately 80 per cent of Syrian refugees in Jordan live in informal tented settlements among host communities in urban areas in the north of the country. The remaining 20 per cent live in the Zaatari (considered to be the second largest refugee camp in the world), Marjeeb al-Fahood, Cyber City and Azraq camps, built on land provided by the Jordanian authorities.

The UN humanitarian appeal for Syrian refugees is only 45 per cent funded. Due to the shortage in funding, the most vulnerable Syrian refugees in Jordan receive approximately JD20 a month, the equivalent of US$28—less than $1 a day. This means that more than 80 per cent of Syrian refugees in Jordan are living below the local poverty line. Syrian refugees also struggle in Jordan to find jobs to help them survive, since it is illegal for most of them to work under Jordanian law. So they accept low-paying and odd jobs that Jordanians usually would not fill. If they are caught, they risk being deported back to Syria. Some children have also been forced to work to secure food for their families.

Since visiting the formal gated Zaatari and Azraq camps required government permission, we were only able to visit the informal tented settlements in both camps. Our itinerary was arranged by Catherine Ashcroft, resource mobilisation specialist, consultant to Mercy Corps and founder of Helping Refugees in Jordan (HRJ), with whom we have been collaborating with for the past year. Catherine is also a mother of three and above all a humanitarian who has dedicated her time and effort for this cause. Her motto is “if a child needs shoes, it doesn't matter where they are born.”

Catherine has transformed her garage into a deposit point for donations such as clothing, shoes, blankets, mattresses, heaters and wheelchairs, and her living room has become a small bazaar where she sells handicrafts, scarves and carpets to raise funds. Last year Catherine's projects raised almost half a million dollars. 102 one-ton trucks, each carrying blankets, clothes and shoes, food boxes and school furniture were transported to refugees across Jordan, without any administrative charges.

Catherine Ashcroft's garage has become a deposit point for donations. PHOTO: Noon Arabia

On our first day we travelled to Azraq in Northern Jordan, and visited a school built with the help of donations collected by HRJ and Mercy Corps, which is being run in collaboration with the Azraq Women Association. It comprised four caravan classrooms housing grades 1 to 4, a small playground, and a fifth caravan that serves as a sewing training center. The students attending the school were Syrian refugees living in the village, as well as some Jordanians. New donations allowed for the construction of a library and workshop hall on a floor above an existing office building.

We then went to visit a new site which was being prepared for more tented classrooms and caravans. The head of the Azraq Women's Association told us the area would be used on mornings as a school, and in the afternoon for workshops and a training project that would create job opportunities for Syrian refugees. Jobs such as selling homemade food and traditional handicrafts would generate income and help improve the living standards of Syrian refugees.

“. . . . as we sat in a tented school that was being prepared we felt the children’s eagerness to resume their educations. Many had been out of school for the past four years, but excitedly recounted what they still remembered.”

Later that afternoon we visited an informal tented settlement in Northern Azraq. There were a few tents sheltering several families each, and we were all alarmed at the miserable living conditions. There was an obvious lack of sanitation and medical care and some of the children's growth was stunted due to malnourishment. Yet as we sat in a tented school that was being prepared we felt the children’s eagerness to resume their educations. Many had been out of school for the past four years, but excitedly recounted what they still remembered. UNICEF was able to provide them with only two teachers only who visit them twice a week, as the distance and off-road journey makes this area harder to access. We left that camp heavy-hearted, feeling that the support provided by our donations was just a drop in the ocean.

A caravan classroom in a camp in Azraq, Jordan. PHOTO: Noon Arabia

Early on our second day we stopped at Catherine's house and loaded one of the cars with jackets, shoes, heaters and powdered milk and headed to Zaatari village. When we reached the village, we stopped at a local organization called White Hands for Social Development and were briefed about its activities in support of Syrian refugees and the local community, such as micro-loans for small businesses and awareness workshops. The organization’s head accompanied us on our visit to some of the settlements there.

The first tented settlement we visited was in the middle of nowhere, with a tank the only water source for all the families living in the tents scattered around it. Despite the difficulty of their living conditions, the children greeted us with a smile, and in a classroom we visited we saw their colourful drawings on its walls. As we drove away, we saw the men being dropped off by a truck after a day's work in the fields. How much had they had earned that day, I wondered.

“I had. . . wondered why some families would choose to leave the established gated refugee camps set up by the Jordanian government and UNHCR, and opt to live in the informal tented settlements with barely any support. I learned that life in the gated camps wasn't much of a life either.”

Then we visited another informal tented settlement in a private gated farm. We delivered some heaters and checked on the progress of another school. The children wore winter clothing yet didn't have either socks or shoes to protect against the cold weather. The tents didn't look like they would survive a heavy rain, let alone the harsh winter ahead. As we headed back to Amman we heard on a weather forecast that a storm would hit the area in the next few days. We were daunted by that thought, but were later comforted by the news that the tented schools we had visited had all been all waterproofed with extra tarpaulins and ropes before the storms hit.

Before going to Jordan, I had been following news about the Syrian refugee crisis and was familiar with accounts of the hardships. But what we witnessed there during our short visit was truly devastating. Syrian refugees in the informal settlements were in need of proper shelter, food and clothing. What struck me the most was the condition of the children, Syria's future generation. They not only needed proper homes, but health care and formal education. Many of the children had been out of school for years, imposing serious limits on their possibilities for the future.

Shahd is one of many children growing up under difficult circumstances in Jordan's refugee camps. PHOTO: Noon Arabia

I had also wondered why some families would choose to leave the established gated refugee camps set up by the Jordanian government and UNHCR, and opt to live in the informal tented settlements with barely any support. I learned that life in the gated camps wasn't much of a life either. They were overcrowded, offered only limited job opportunities and were generally not safe. Those living in them often feel trapped, unsafe and desperate—though by moving outside the camps they were mere exchanging one set of hardships for another.

As the Syrian conflict enters its fifth year, and as the situation deteriorates and becomes more desperate for Syrian refugees, their hope of returning to Syria is starting to fade. After my time among Syrians who have sought refuge in Jordan, I understood why some choose to risk everything and cross hazardous waters to find better living conditions in Europe. The driving force is job opportunities and an extra income that they could send to their relatives back in Syria, and, moreover, the hope of a securing a better future for their children.

For more information about Catherine Ashcroft's work with Syrian refugees in Jordan, visit the Helping Refugees in Jordan Facebook page.

2 comments