The original version of this post appeared on the Future Challenges blog.

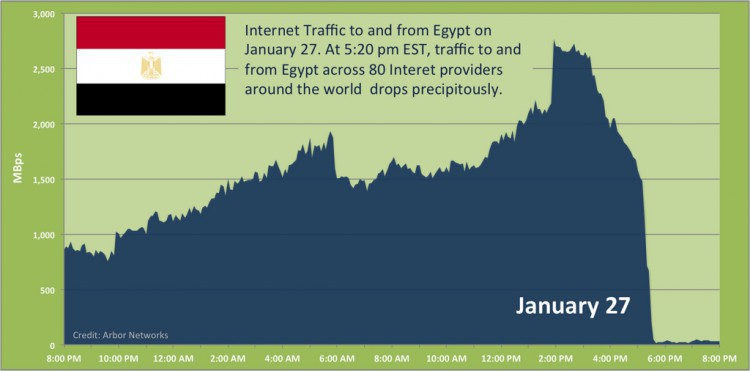

On January 27, 2011, Egyptian authorities ordered a total blackout on all digital communications in order to stem the growing calls for protests in the street to topple former President Hosni Moubarak. The blackout went on for six days during which Egypt completely disappeared from the Internet. This was unprecedented in scale and in duration. The strategy eventually backfired, demonstrating the regime’s inability to tackle popular anger.

The digital technology was not only a political paradigm shift for the Egyptian officials, it was also an alien and probably risky one as well. Social media tools were used by young Arab activists to voice dissent and spread it in a very effective way, so effective that the Arab spring was labelled a digital revolution. The mere fact that there was social media created a new rapport de force between the regime and the people. This new media, by its simple existence, created a counter weight to the power of the regime. And ever since, its presence has affected the way Egyptians consume information. The authorities were seen as digital migrants, not at ease in these new territories where control and censorship were more complicated than on traditional media.

Egyptian authorities today must figure out how to communicate effectively in the wake of four years of constant regime change.

Over the last four years, Egypt has witnessed a series of regime changes. Before the 2012 presidential elections that led to the election of Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood, the first regime change came with the installation of a Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) as an interim government. The second regime change came when Morsi was ousted by a popular revolution backed by the army during the summer of 2013. Then in May 2014, a former Field Marshal by the name of Abdelfattah Al Sissi was elected President.

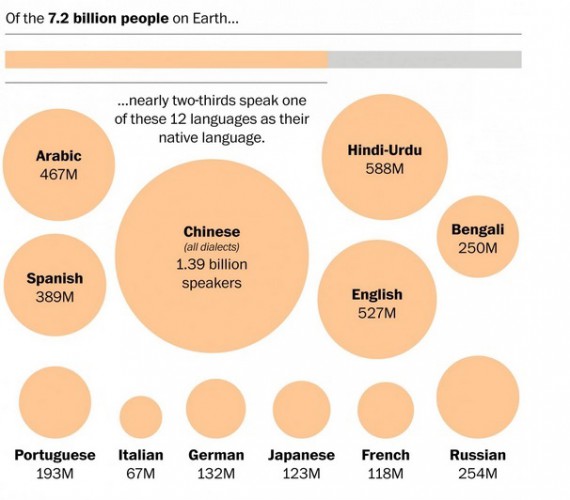

Despite the regime changes and their impact on diplomatic issues, a non-Arabic reader would not be able to really know what was going on. Digital tools were barely used by Egyptian authorities and when they were, it was exclusively in Arabic. Take for example the following websites, the official page of the Egyptian Army spokesperson, the official YouTube channel of the Egyptian Minister of Foreign Affairs, the official Twitter account of former President Muhammad Morsi and the official Twitter account of current President Abdelfattah Al-Sissi, these provide important updates on the situation in Egypt. But updates are written only in Arabic, despite the fact that most of the world does not read this language.

Is Egypt missing out by only communicating in Arabic?, source: U. Ammon, U. of Dusseldorf, Population Reference Bureau (includes bilingual speakers).

The population addressed by such e-diplomacy efforts already had access to traditional media tools in Arabic as well. But, the rest of the world, be it English, French or Spanish speakers, was left in the dark. The only English-language media available is https://twitter.com/MfaEgypt. It began in January 2015 and has less than 700 users.

Welcoming digital technology into the political space?

Now compare this with the creative “e-diplomacies” of the region, for example Israel, who have developed targeted social media accounts and strategies for regions in which they have no official diplomatic presence. Even ISIS has been implementing very elaborate digital strategies, using multilingual digital tools such as social media, online newspapers, high-definition video cameras, slick graphics and refined editing techniques. As scholars Gregory Payne, Efe Sevin and Sara Bruya write,

Old methods of diplomacy based on behind-the-scenes diplomacy, relying heavily on one-way communication methods where the audience usually plays a passive role. However, given the possibilities for active engagement that exist in today’s media landscape, individuals are less likely to accept this passive, submissive role.

Egypt seems to be stuck in this old way of doing diplomacy.

Yet Egyptian authorities are capable of addressing the “international community” in a clear and professional manner, as demonstrated during the Egypt Economic Development Conference in March 2015. They had a fully functioning website, including a dedicated Twitter account and hashtag (#EEDC2015) and a YouTube channel specifically for videos from the conference.

The Egyptian government has demonstrated the ability to fully implement a social media strategy, for example, in the recent Egyptian Economic Development forum. This saw a targeted, successful and open mode of communication accessible to many people. However, this same openness isn’t translated to its own international diplomatic efforts, which begs the question: Why not?

Why can’t this be replicated throughout Egypt’s global e-diplomacy? Why not take advantage of social media platforms to build a successful digital diplomacy strategy? What’s preventing the authorities from taking part in a broader, more open conversation regarding the kind of societies we want and the interactions among them and within them? Technology and social media have provided diplomacy with additional tools to do just that, but it entails a complete overhaul in Egypt’s communications strategy.

3 comments