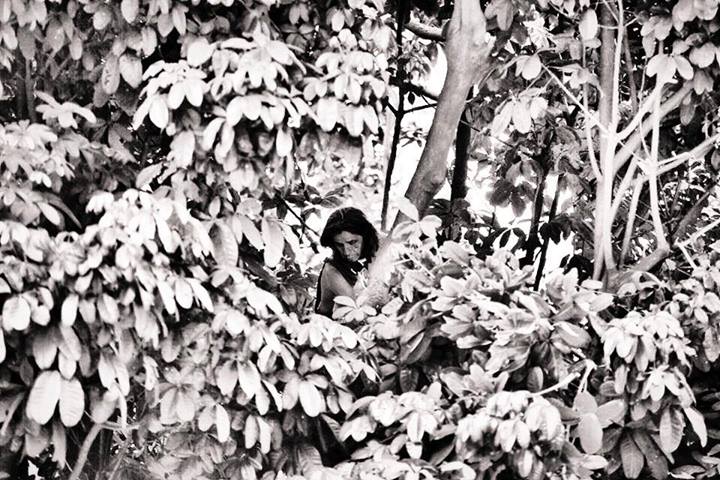

Urutau resisted for 26 hours at the top of a tree in protest against the removal of the occupation of Aldeia Maracanã. Photo: Facebook/Mídia NINJA

[All links lead to Portuguese-language pages except when otherwise noted. The original version of this post, in Portuguese, was published on December 19, 2013.]

On the morning of December 16, while a battalion of riot police of the Brazilian military police forcefully removed activists that had occupied one of the buildings of the former indigenous museum Aldeia Maracanã in Rio de Janeiro, José Urutau Guajajara, the leader of the Guajajara tribe, ran. At 64 years old, Urutau – a name that means owl in the indigenous language Tupi – climbed a tree as a form of protest against the eviction. And there he stayed for 26 hours.

At the end of the morning on December 17, 2013, Urutau was removed from the tree by firefighters and taken away in an ambulance. A diabetic, Urutau had access to water, controlled by the police. But beyond that, according to information from the activist media collective Mídia NINJA, police prevented any attempted delivery of food to him. Supporters of the occupation, who witnessed Uruatu's resistance, tried to circumvent the blockade by throwing food to him. According to independent media group ZUMBI, Urutau was taken directly to the police station, instead of being taken to the hospital.

The indigenous man demanded that a judicial order justifying the eviction be presented. According to information from the activist media group Olhar Independente (Independent Look), the judicial decision authorizing the eviction presented by the police was old, and as such, was no longer valid. A story published in the newspaper Extra confirmed the situation, revealing that an unidentified police officer had said that the orders were “not to evict them” because the action was “illegal.”

The Aldeia resists and insists

The mobilization around the occupation, which started on December 14, and Urutau's fight were followed on Facebook and on Twitter, with the hashtag #AldeiaResiste (Aldeia resists). International movements, such as the Spanish Take the Square [en] and Occupy Wall Street [en], also spoke out in support of the Brazilians.

The 14,000-square-meter complex that makes up Aldeia Maracanã, or Maracanã Village, was donated to the Indian Protection Service in 1910. From 1953 to 1977, the buildings served as the headquarters for the Museum of the Indian; however, since the change in location of the museum, the buildings have been abandoned. In 2006, indigenous from 20 different ethnicities reoccupied the locale.

Indigenous in one of the buildings of the complex. On the wall it reads, “Want to kill a people? Then rob them of their culture.” Photo: Facebook/Aldeia Maracanã

In August of 2012, the state government and the city government of Rio de Janeiro announced that the place would be demolished to make way for construction for the 2014 World Cup, as it is near the Mário Filho Stadium, known as Maracanã, which is the name of the neighborhood where the former museum and stadium sit. A petition asking for the recognition of the indigenous ownership of the village was created on Avaaz, explaining:

Neste local, indígenas de várias etnias vêm difundindo sua cultura há seis anos e em escolas particulares e públicas,exercendo direito garantido pela lei. Defendemos a criação de um centro de referência da cultura indígena.

In this place, indigenous people from various ethnicities have been disseminating their culture for six years, as well as in private and public schools, exercising their rights as guaranteed by the law. We defend the creation of a center of reference for indigenous culture.

During that time, indigenous representatives fighting for the village appeared in a video explaining their case:

The space was occupied four times in 2013, the first time in March [en]. A decree signed by Mayor Eduardo Paes in August, the time of the last occupation, recognizes the presence of the Maracanã Village community and provides for the definitive protection of the main building - which means that it can no longer be demolished for World Cup construction. At the end of September, “the judge of the 7th Court of the Federal Public Treasury signed a dispatch impeding the demolition” and determined that, without a official pronouncement from the government, the area should be given to the occupants, the indigenous.

Despite the decree and the judge's dispatch in favor of the community, there are no guarantees about the fate of the area, believes Demian Castro, the representative of the People's Committee of the Cup and the Olympics, who told the Brazilian press that the privatization process of the Maracanã complex should be revoked. The consortium that has won the bidding to reform and operate the stadium for the next three decades, Maracana S.A., formed by the companies Odebrecht, IMX and AEG, has presented a new viability plan for the area to the Governor of Rio that is still under analysis.

Without any other solutions to the situation, on Saturday, December 14, activists returned to occupy the space. After an attempted expulsion on Sunday, on Monday morning 150 riot police troops obeying the orders of the state government surrounded the area and carried out a forced eviction of the occupants. Of the 30 people that were in the building, 25 were arrested, but have since been released.

At the end of Tuesday, December 17, after being forbidden from returning to the village, Urutau and other representatives of the group who were evicted from the building joined with students to occupy the rectory of the State University of Rio de Janeiro- UERJ. They asked for a meeting to discuss the Museum of the Indian project.

On January 6, 2014, the government of Rio released a note announcing that the contract with Maracana S.A. has been changed in order not to allow the demolition of the building of the Museum of the Indian.

3 comments