In her society, openly expressing desire was deemed inappropriate for a woman, yet she was expected to remain alluring in private. These conflicting expectations of being the ideal partner colored her experiences.

Luckily, Jane’s husband empathised with her unease and provided support by urging her to accept her sexuality. After years of exploration, their bond strengthened, resulting in a fulfilling intimate relationship.

Uganda has diverse cultures and languages, where words wield significant influence, capable of inspiring or causing harm. Sexuality plays a crucial role in this context. Several traditions and words used in the country, which are deeply rooted in culture, inadvertently contribute to narratives that perpetuate sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV).

To delve into this complex subject, we must analyse past societal shifts, cultural standards, and the impact of Western influence. Is there a possibility that something got lost in translation? What factors make intimate relationships more susceptible to abuse?

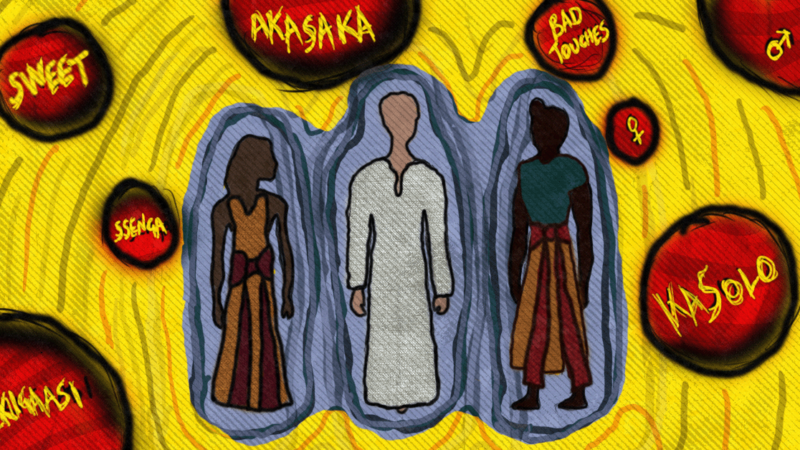

In Luganda, one of Uganda's major languages spoken by the Baganda people, the term kasolo (meaning penis) literally translates to a small animal. This linguistic nuance can imbue men with a sense of power in personal interactions. The “small animal” suggests a constant readiness to attack, contributing to narratives of terror and associating men with animalistic behavior, portraying them as the “hunter.” Consequently, violence from men, depicted as the “small animal,” may be perceived as almost expected and potentially even rewarded.

Conversely, using softer terms like “sweet” to refer to the vagina reinforces a narrative of delicate femininity. These terms are not merely decorative; they carry significant meanings that shape perceptions. They establish a framework for mistreatment by defining men's actions and women's moral obligations in relation to their bodies. This narrative limits women's autonomy in making choices about their sexuality, surveils their behavior, and assigns blame to them in cases of abuse. Women may feel compelled to conform without even realizing it, as their roles are predetermined by the language employed.

This linguistic framing shines a light on an aspect often ignored when dealing with abuse in relationships. The way language is used not only shows a power dynamic but also dictates how people should behave in romantic or sexual situations. Women’s desires and boundaries take a backseat to societal norms that prioritise male dominance and control.

In the past, Ssengas, played a crucial role within the Baganda community in facilitating discussions about sexuality. Young girls frequently sought advice from their aunties on topics such as adolescence, sex, relationships, and womanhood. These conversations played a significant role in guiding girls into adulthood by imparting knowledge about marriage and gender expectations.

While the Ssengas’ influence was vital in marriage as they provided valuable insights, their teachings also inadvertently reinforced certain problematic gender stereotypes.

According to researchers, in certain Ugandan ethnic groups like the Batooro, sex education is primarily provided by paternal matriarchs, including the paternal aunt, mother, and grandmother, and post-marriage by in-laws such as the mother-in-law, sisters-in-law, or husband’s grandmother. Historically, and still in some areas today, girls were also instructed on their first night of marriage on how to engage in sexual intercourse.

This education often occurs within specific contexts, such as the akasaka – a private, secured space in the home adorned with a special grass called ekigaasi, where girls receive instruction on sex-related matters. Participation in the akasaka is expected both before marriage (at the parents’ home) and after (at the husband’s). Before marriage, girls are taught about “bad touches,” emphasising that public displays of sexual affection like kissing are prohibited.

After marriage, participation in the akasaka continues, with the mother-in-law helping the new bride navigate her role within the family. While this orientation aids in the bride’s integration into the household, it often reflects the traditional understanding of women’s subservient role within the home.

Sex education for boys is also emphasised and typically provided by fathers, uncles, and grandfathers. Unlike girls, though, boys do not have a dedicated session for sex education but rather receive continuous informal education as opportunities arise.

Sylvia Tamale, a legal scholar, emphasises the importance of addressing discussions on sexuality to fully understand societal norms. Tamale highlights how the dominance of Western colonialists’ language in discussions about sexuality shapes the meanings and definitions of related concepts to reflect experiences outside Africa.

She illustrates this with the example of silence. In many Western cultures, silence is often interpreted as a sign of submissiveness or yielding to power. However, in certain cultures, particularly among the Baganda, some women have transformed silence into a potent form of action. For instance, the Ssenga institution teaches women that it’s better to ask and make requests during sex, underscoring the connection between expectations and personal choices. This demonstrates how cultural environments shape the understanding of actions and empower individuals to redefine traditional roles in meaningful ways.

Today, Jane is approaching the topic of sex with her children in a unique manner. She openly addresses topics related to sex and abuse and encourages her children to have open conversations with her and her husband about their bodies and relationships.

She is a firm believer that leading by example is the most effective way to teach. She and her husband share a strong bond, frequently engaging in conversations about their children’s well-being, family finances, and the future of their family. “We are reshaping gender roles and educating our children about the partnership between a man and a woman in marriage,” Jane says with happiness.