“No war. Saint Petersburg. The inscription was made on the first day of the war.” All screenshots from www.nowobble.net, used with permission

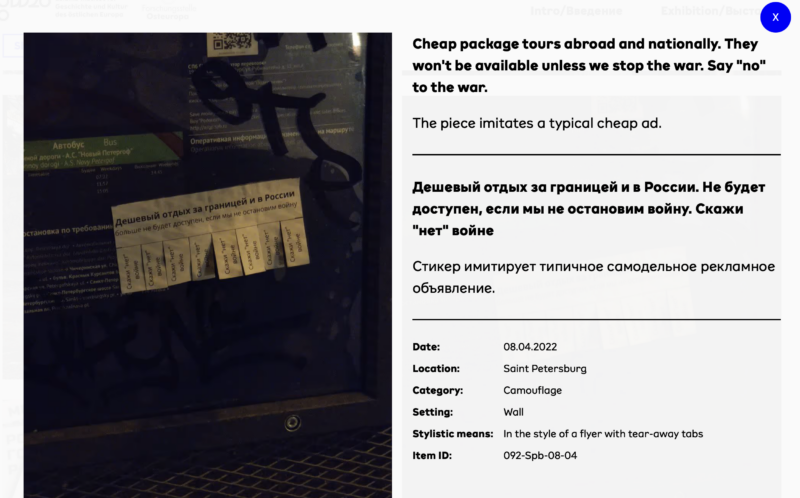

Russian anthropologist Alexandra Arkhipova and her colleagues have been collecting the examples of anti-war street-art — stickers, graffiti, leaflets, and complex installations — for 1.5 years. Now, everyone can see photos of 471 works from 48 Russian cities meticulously classified, carefully translated into English and clearly explained in one place.

Read more: The main effort of Russian propaganda language is to give the impression that there is still no war

The website “No wobble” showcases the artwork, and also the story of the symbols and the Aesopian language that appeared in Russia after February 2022 and how it was used in protest art. The name of the website is the perfect example of that.

Read more: Russian social media users now also want to say no to war while not actually saying it

The website explains: “In Russian, ‘war’ (voina) and ‘wobble’ (vobla) sound similar and have the same number of letters, which is important for the coded language.”

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

At the same time, the idea of the collection came from the personal experience. Shortly after the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, one of the website future authors found out that his underage daughter was drawing “No war” stickers and with her friends sticking them in the subways and on the streets. He decided to distribute the rest himself and, while doing so, was “shaking and sweating”.

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

His fear wasn’t baseless. People in Russia are fined or even jailed for less, like a green ribbon — a symbol of peace — in a braid. While many messages are seen just by passers-by, some graffiti or installations make it to the news. On Russia Day, a national holiday, the neologism “Изроссилование” (Izrossilovaniye) that combines the words ‘rape’ and ‘Russia’ appeared in many feeds. Some time later its author was arrested.

художник Philippenzo задержан на погранконтроле после возвращения в Россию. вменили пока 19.3, арест на 15 суток

его последняя работа в Москве 12 июня: pic.twitter.com/5E9ToUyfCG

— артём лоскутов (@kissmyba) July 29, 2023

Artist Philippenzo detained at the border control after he returned to Russia. He got 19.3 [article of the Russian Code of Administrative Offences ‘Disobedience to a lawful order or request of a police officer’], 15 days in jail. His last work in Moscow was on June 12, 2023.

Even though, according to the website, at least 653 people were caught applying stickers or drawing graffiti, to many street art is still the safest way to express their anti-war or anti-regime sentiments.

Read more: Russian artist Alexandra Skochilenko addresses the court in Saint Petersburg at her trial over anti-war messages

People continue to post stickers, draw messages, place tiny figures, and even create complex graffiti with well-known quotes, while carefully keeping a wary eye on their whereabouts in case there are CCTV cameras, police officers, or vigilant ‘patriots.’

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

Global Voices spoke to Alexandra Arkhipova on Telegram and asked her whether this kind of protest existed in the past.

In Soviet times, of course, there was protest street art. The famous Tram Protest by artist and dissident Yuli Rybakov. This kind of protest existed, just not on such a scale, and peculiar not only to the Soviet Union. For example, in [fascist] Italy, when they wrote “Viva Verdi!” on the walls, it was deciphered as “Live long Victor Emmanuel II, King of Italy.” The same thing in Soviet times, in place of the Soviet power [sovetskaya vlast] was said “Sofia Vlas.” The mechanism is the same. Exactly the same thing is used now: instead of the Presidential Administration [Administratsiya Presidenta] people say Anna Pavlovna. It always arises when there is some kind of pressure. When people's public voice is taken away, they start trying to look for some kind of way out.

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

According to Arkhipova, such disguises and ciphers “are blossoming in China.” It's enough to recall the story with the ban on Winnie the Pooh. There is such a thing in Belarus, too. Except that, in order to show it, someone needs to collect it.

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

She continues. “An inscription, a sticker, an installation is first and foremost a form of statement; therefore, it has two forms. The first is to create something in public space. And the second, the next one: to make it spread in the digital space. That's why the evolution of these forms is so strange. The most engaging, the most eye-catching inscriptions, the cleverest ones that attract attention are selected so that people take pictures of them.”

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

“Of course, a number of insurgent people spread these kinds of inscriptions. There are protest Telegram channels, like Protest Petersburg, [journalist Roman] Super's channel. However, there's a source problem because very often people take a photo and it turns out to be from 2019, for example. Or, in the Super’s channel, one graffiti appeared several times with wrong dates. That's why I always asked to send what people saw with their own eyes, or what their friends or family really noticed in their city,” Arkhipova said.

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

“I have a lot of photos from St. Petersburg, where the protest activity is just frenzied. When the exhibition was published, a lot of people wrote to me asking why I didn't mention their city as well as sending me a whole bunch more of the freshest graffiti from just this month,” she told Global Voices.

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

“It is important for me to expand the geography, to write not only about Moscow and St. Petersburg, but what is happening in, let’s say, Smolensk, because the responsibility for graffiti in Smolensk may be higher than in Moscow as any protest activity in Smolensk attracts more attention,” Arkhipova concluded.

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

Alexandra Arkhipova doesn't know if the collection on the site will be replenished, but she saves everything that is sent to her. She believes street art should definitely be studied, but, so far, it is a highly underrated phenomenon, especially in Russia.

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

“People try to pay attention to the works of professional artists who have complex performances. And such works are also in this exhibition, but I also tried to collect and show things that simple John Smith does at night. Or a schoolboy. Those people who are not art professionals, for whom in general this type of expression is in no way immanent. It seems to me that in a way it is much more important, because art historians will deal with professionals. And who will deal with what John Smith does at night?”

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

According to Arkhipova, many people have found a solace in such quiet protest, but it has also become a way to find allies, which is also very important.

Screenshot from www.nowobble.net, fair use.

Here's a person going at 3 a.m. in Yekaterinburg to stick “No to war” stickers and, sneaking up to a pole, they find another person's “No to War” sticker there. And they feel tremendous joy, because they realize that there is an ally. Propaganda makes people lonely. It seeks to show that any person who thinks differently is in a significant minority. This is why there is such a big battle for the ability to speak out in public space. As one of my interlocutors said, here's John Smith leaving the house to get bread. He gets into the elevator and sees a sign that reads “No to war.” He goes out to the entrance and sees a sticker “Down with Putin.” He goes to a bus stop, and there's something anti-war there too. He buys a loaf of bread and there's a “Remember Bucha” sticker on it. All of this is to make the statement strong, to show that there are many people around who are against the war.