Photo by Katia Buffetrille illustrating the book “Amnyé Machen, Amnyé Machen”. Photo used with permission.

Following the Dalai Lama’s escape in 1959 and Beijing’s policy of compulsory sinicization, many Tibetans were compelled into exile. Consequently, contemporary Tibetan literature is produced in different languages. Furthermore, the younger generations, who have grown up outside of Tibet, write in languages such as English or Chinese.

The case of Tsering Woeser, a blogger, poet, and novelist, is indeed unique: originating from a Tibetan family, she speaks Tibetan fluently, yet has chosen Mandarin Chinese as her primary writing language. While her creativity flows freely, she faces publication bans and travel restrictions imposed by the Chinese authorities. Recently, a collection of her poems, recounting a pilgrimage around a sacred mountain in Tibet titled ‘Amnyé Machen, Amnyé Machen,’ has been translated into French, complete with photographs. The project is a collaborative effort featuring the author herself, the publisher, translators, a Tibetologist, and a photographer.

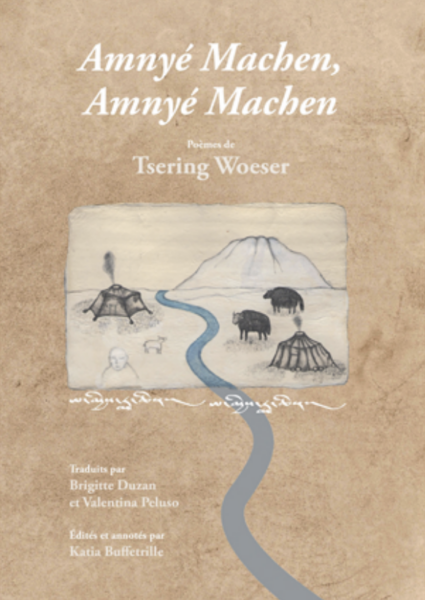

Book cover. Reproduced with permission

Global Voices conducted interviews with several participants following a September gathering in Paris at the Festival du Tibet et des Peuples de l'Himalaya [festival of Tibet and the Himalayan People]. Among those present was Jérôme Bouchaud, the editor of Jentayu magazine, which specialises in showcasing Asian literature in French translation. This event also marked the publication of their first book. Also present was Brigitte Duzan, a researcher, Chinese translator, and founder of two reference websites: Chinese Movies, dedicated to Chinese cinema, and Chinese Short Stories, which focuses on modern and contemporary Chinese literature. Another notable attendee was Katia Buffetrille, an ethnologist and Tibetologist who not only studies but also participates in pilgrimages around sacred mountains. She documents the transformations these pilgrimage sites undergo due to modernisation, while also observing recent phenomena such as self-immolations.

Propaganda sign about the ‘Chinese dream’, photo by Tsering Woeser, used with permission.

Jérôme Bouchaud. Photo used with permission.

Filip Noubel (FN): Jentayu started out as a French-language magazine focused on Asian literature. How is the transition to book publishing going? What is the role of Asian literature within the French-speaking readership?

Jérôme Bouchaud (JB) : La revue Jentayu et ses dix numéros auront été une formidable aventure, mais la cadence semestrielle de parution m’était devenue difficilement gérable. D’où mon choix de m’investir plutôt dans des projets d’édition au long cours. Le recueil de Tsering Woeser, “Amnyé Machen, Amnyé Machen”, aura ainsi pris plus de deux ans entre l’accord de l’auteure et la publication en septembre dernier. Un cercle de cinq personnes — les deux co-traductrices Brigitte Duzan et Valentina Peluso, ainsi que Katia Buffetrille, Woeser et moi-même — aura travaillé à la réalisation du recueil.

Les tâches restent foncièrement les mêmes — traduire, éditer, promouvoir — mais le curseur se déplace de l’urgence vers l’exigence. La traduction et la relecture du recueil se sont avérées très complexes, tout comme la sélection des photographies, et il aura vraiment fallu nous accorder le temps de tout bien faire. Par ailleurs, le fait de publier l’œuvre complète d’un seul auteur implique que les liens noués entre elle et les éditions Jentayu sont d’autant plus forts. Nous sommes devenus, au moins pour le temps d’un livre, sa maison, et c’est un honneur immense pour nous que de l’y accueillir. Elle sera ici toujours chez elle.

Pour ce qui est de la place des littératures d’Asie en traduction dans le lectorat francophone, si l’on en croit les statistiques, elle reste très limitée hormis pour le japonais, qui bénéficie du phénomène manga. La littérature traduite représente chaque année entre 15 et 20% de la production éditoriale totale en France. Parmi toutes ces traductions, le chinois ne représente par exemple qu’un peu moins de 1%, ce qui en fait la première langue d’Asie traduite, après le japonais. Bref, la route est encore longue, mais l’action continue d’acteurs importants — traducteurs, éditeurs, libraires — font que les choses évoluent doucement dans le bon sens.

Jérôme Bouchaud (JB): The Jentayu magazine and its ten issues have been a wonderful journey, but the biannual publication rhythm had become increasingly challenging for me to manage. So I decided to shift my focus more towards long-term publishing projects. The collection by Tsering Woeser, ‘Amnyé Machen, Amnyé Machen,’ took over two years to complete, from the author’s agreement to its publication last September. Five individuals — the two co-translators Brigitte Duzan and Valentina Peluso, as well as Katia Buffetrille, Woeser, and myself — worked together to bring this collection to fruition.

The fundamental tasks remain the same — translating, editing, promoting — but the focus has shifted from a sense of urgency to being more rigorous. The translation and proofreading of the collection turned out to be very complex, as did the selection of photographs, and it was truly necessary to give ourselves the time to do everything properly. Moreover, publishing the complete work of a single author means that the bonds formed between her and Jentayu Editions are all the stronger. We have become, at least for the duration of a book, her home, and it is an immense honour for us to welcome her. She will always be at home here.

Regarding the presence of Asian literature in translation within the French-speaking readership, statistics show that it remains quite limited, except for Japanese literature, which benefits from the manga phenomenon. Translated literature represents annually between 15 and 20 percent of the total editorial production in France. Among all these translations, Chinese, for instance, represents just under 1 percent, making it the most translated Asian language after Japanese. In short, there is still a long way to go, but the continued efforts of significant players — translators, publishers, booksellers — are gradually steering things in the right direction.

Katia Buffetrille. Photo used with permission.

FN: What do pilgrimages around sacred natural sites represent, and how are they changing?

Katia Buffetrille (KB): Un Tibétain définissait le pèlerinage comme « l’offrande religieuse du laïc ». Le pèlerinage au Tibet est la pratique essentielle des laïcs, mais pour autant, ils ne sont pas négligés par les religieux. Si les pèlerins se rendent vers des sites construits par la main de l’homme, leurs pas les dirigent souvent vers des lieux naturels (montagnes, lacs et grottes).

Le pèlerinage au Tibet est un phénomène social total, associé à diverses activités rituelles et porteur d’une dimension sociologique, culturelle, économique, politique, littéraire et bien entendu, religieuse. Par cette pratique, le pèlerin cherche à obtenir une meilleure réincarnation mais également à améliorer son sort ici-bas, espérant l’obtention de biens matériels. Les montagnes sacrées, considérées à la fois comme la résidence du dieu du terroir et le dieu lui-même, peuvent répondre à cette attente. Ce dieu du terroir, dieu des croyances non-bouddhiques est, de nos jours encore, l’objet d’un culte ; mais sous l’influence du bouddhisme, la pratique de la circumambulation s’est imposée et les pèlerins tournent autour des montagnes comme ils tournent autour d’un temple.

L’invasion chinoise des années 1950 puis l’occupation ont eu un impact considérable sur la vie religieuse; mais pas seulement. La pratique du pèlerinage est confrontée de nos jours à la sinisation, la modernisation, la bouddhisation, phénomènes qui se chevauchent, auxquels il faut ajouter les conséquences du réchauffement climatique. Alors que l’importance d’effectuer un pèlerinage à pied a été théorisée par de grands maîtres, la construction de routes autour des montagnes sacrées pousse de nombreux pèlerins à venir en voiture. Ainsi, le pèlerinage autour de l’Amnye Machen requiert huit jours à pied, mais seulement un en voiture. Cela permet à des gens de régions plus lointaines de venir, mais qu’en est-il de la purification des actes négatifs que les efforts accomplis permettaient d’obtenir ?

Katia Buffetrille (KB): A Tibetan defined pilgrimage as ‘the layperson’s religious offering.’ In Tibet, pilgrimage is the essential practice for laypeople, yet it is not neglected by the religious community. While pilgrims do visit manmade sites, their steps often lead them towards natural settings (mountains, lakes, and caves).

Pilgrimage in Tibet represents an all-encompassing social phenomenon, intertwined with various rituals, and bearing sociological, cultural, economic, political, literary, and of course, religious dimensions. Through this practice, pilgrims seek not only a better reincarnation but also seek to improve their worldly existence, hoping for material blessings. Sacred mountains, regarded simultaneously as the abode of the local deity and as the deity itself, can fulfil these aspirations. This local deity, rooted in non-Buddhist beliefs, continues to be worshipped today. However, under the influence of Buddhism, the practice of circumambulation has become prevalent, with pilgrims circling the mountains as they would a temple.

The Chinese invasion in the 1950s and the subsequent occupation have had a profound impact not just on religious life, but on other aspects of society as well. Presently, the practice of pilgrimage faces challenges from sinicisation, modernisation, buddhicisation — overlapping phenomena — to which we must also add the consequences of climate change. While the importance of undertaking a pilgrimage on foot has been theorised by great masters, the construction of roads around sacred mountains encourages many pilgrims to travel by car instead. Consequently, the pilgrimage around Amnye Machen, which requires eight days on foot, can now be completed in just one day by car. This makes it accessible to people from more distant regions, but it raises the question: what becomes of the purification of negative deeds that was once achieved through the physical effort of the journey?

Brigitte Duzan. Photo used with permission.

FN: What are the main challenges in translating a Sinitic text rooted in Tibetan cultural realities into French?

Brigitte Duzan (BD): Traduire dans une langue comme le français un texte écrit en chinois par un auteur tibétain comporte toujours une part de difficultés, sinon de défis. La principale difficulté est de comprendre la réalité culturelle et religieuse, qui se cache derrière un terme, l’auteur étant forcé de recourir à la transcription/translittération en caractères chinois d’un mot, ou d’une expression recouvrant une notion, un personnage, une divinité typiquement tibétains.

L’exemple-type de chausse-trappe est le terme de huofo [活佛] qu’il s’agit de ne pas traduire dans son acception littérale de « bouddha vivant », mais dans son sens réel de lama réincarné, ou tulku, avec éventuellement une note explicative en bas de page, selon le texte. Tsering Woeser le souligne dans sa préface : « la langue dans laquelle j’écris n’a rien à voir avec cette langue ».

Dans le cas des poèmes de Tsering Woeser, les difficultés sont accrues par le fait qu’ils traduisent son monde intérieur. Il s’agit donc non seulement de traduire mais de découvrir « Tout ce qui est caché dans cette langue dont je me sers », selon ses propres termes. C'est encore plus vrai de ce recueil qui évoque tout ce que la déambulation autour de la montagne a de révélateur d’une profonde religiosité qui sous-tend le moi de l’auteure. Le bouddhisme est omniprésent à chaque pas, mais aussi les idées qui lui viennent en tête au détour du chemin, parfois nées d’une histoire qu’on lui a racontée, à retrouver ou reconstituer.

Les photos de Katia, sa connaissance du pèlerinage et de l’auteure, ont beaucoup aidé à comprendre ce « sens caché dans la langue ». La traduction s’est faite à quatre mains, en parfaite symbiose. Il pouvait difficilement en être autrement. Il a parfois fallu faire appel à l’auteure pour comprendre, mais parfois la solution est venue… du journal de bord que tenait Katia pendant le pèlerinage. On peut parler d’une traduction de découverte comme on parle d’un voyage de découverte.

Brigitte Duzan (BD): Translating a text written in Chinese by a Tibetan author into a language like French always entails a degree of difficulty, if not challenges. The main difficulty lies in understanding the cultural and religious reality hidden behind a term, as the author is forced to resort to the transcription/transliteration in Chinese characters of a word, or an expression covering a concept, a character, a deity that is typically Tibetan.

The term huofo [活佛] is a typical example of such a challenge. Instead of translating it in its literal sense as ‘living Buddha,’ it should be translated in its actual meaning of ‘reincarnated lama,’ or ‘tulku,’ possibly accompanied by a footnote explaining the term, depending on the context of the text. Tsering Woeser emphasises this in her preface, stating: ‘The language in which I write has nothing to do with this language.’

For Tsering Woeser’s poetry, the translation challenges are amplified, as her verses serve as a window to her inner world. Thus, it’s about not only translating but also uncovering ‘everything that is hidden in this language that I use,’ in her own words. This is even truer for this collection, which highlights the deep religiosity woven into the author’s identity, revealed through her pilgrimage around the mountain. Buddhism is omnipresent at every step, as well as the ideas that come to her mind along the way, sometimes born from a story that has been told to her, which she then needs to retrieve or reconstruct.

Katia’s photos, her understanding of the pilgrimage, and her knowledge of the author significantly contributed to deciphering the ‘hidden meaning in the language.’ The translation was a collaborative four-handed effort, in perfect harmony. It could hardly have been otherwise. At times, we had to consult the author to understand, but sometimes the solution came… from Katia’s travel journal kept during the pilgrimage. One might describe it as a translation of discovery, akin to a journey of discovery.

Horses’ skulls. Photo by Tsering Woeser, used with permission.

Note: The author of this article has also contributed to the translation of texts and interviews for Jentayu magazine.