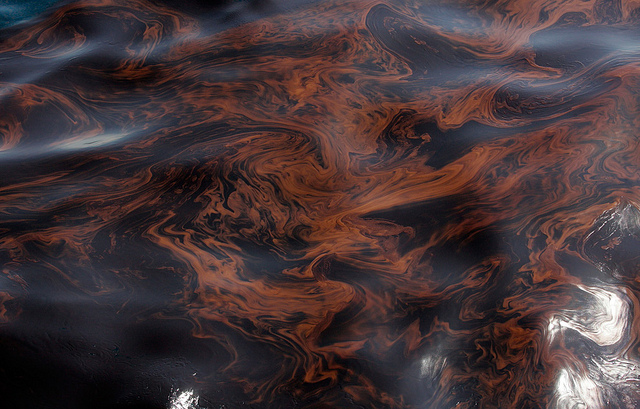

Oil laden water after the spill. Photo on Flickr by user Carlos Quintana (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

There have been two new oil spills in the Amazon jungle. The Northern Peru pipeline, operated by the country's state-owned petroleum company Petroperú, is thought to have contaminated several kilometers of the Saramuro region and the Cuninico gorge (located in the Urarinas district of the province of Loreto). Local indigenous communities have reported children becoming ill with various stomach problems. The extent of the damage to the area's environment and inhabitants remains unknown.

The two spills occurred on June 26 and June 30, but Lima's mainstream media waited several days to report on the disaster, presumably because of Saramuro's remote location. Thus far, Petroperú's response efforts to mitigate the damage (supply food and water to locals) have proved inadequate. Members of native communities in the affected region say the fish and drinking water in the area remain unsafe to consume.

#Derrame de petróleo en oleoducto PetroPerú en Cuninico, Loreto.Población, flora y fauna afectadas. Se necesita ayuda pic.twitter.com/ujDt8n5o6G

— Nelly Luna Amancio (@nellylun) July 10, 2014

Oil spill in PetroPerú's pipleline in Cuninico, Loreto. Population, vegetation, and animals affected. Help is needed.

The public outcry grew when reporters discovered that Petroperú hired minors to work in the company's clean-up effort. Though Petroperú denied the accusations, the story soon appeared on national television, prompting the Minstry of Energy and Mining to reshuffle on Petroperú's management, appointing a new board of directors.

Niños d la localidad d Cuninico n Loreto con enfermedades estomacales tras derrame de petróleo http://t.co/wkCOLB6aU4 pic.twitter.com/Z0fSvC3QYz

— ALEX_TLV_BLANQVIAZVL (@AlexVQ27) July 12, 2014

Children in the Cuninico community in Loreto with intestinal illnesses after the oil spill.

In a newspaper column published July 22, journalist Rocío Silva Santisteban wrote about Petroperú's problematic behavior elsewhere, recounting the experiences of the Kukama people and Manolo Berjón and Miguel Cadenas, two priests from Santa Rita de Castilla parish, in the city of Nauta (Loreto), who have spent time investigating oil spill's damage in the Marañón basin.

1) se aprovechan de la necesidad de los lugareños, sus expectativas de ingresos y su ignorancia sobre las consecuencias del contacto directo de la piel, los ojos, incluso la boca con el hidrocarburo; 2) se contrata a la misma población para tener una limpieza rápida y a bajo costo; 3) se actúa con total impunidad, pues se sabe que en esos parajes es muy difícil que la información circule fuera de los sectores más cercanos. […] Ah… lo olvidaba: los sacerdotes (Manolo) Berjón y (Miguel) Cadenas están siendo chuponeados, reglados y hackeados para evitar más denuncias: ¡y todo en el año de la COP20!

1) They are taking advantage of the local people's needs, their income, their expectations, and their ignorance about the effects that direct contact with hydrocarbons has on the skin, the eyes, and even the mouth; 2) they are hiring the very same people for a cheap and quick cleanup; 3) they are acting with complete impunity, since it is well understood that information in these areas rarely spreads beyond neighboring communities. […] Ah, and I almost forgot: the priests (Manolo) Berjón and (Miguel) Cadenas are being spied on, managed, and hacked to prevent more accusations: and all in the same year as the COP20 [UN climate change conference]!

Cadenas and Berjon, both Spanish Augustinian priests, are well known throughout the region for their humanitarian work in indigenous communities. Since 2010, they've blogged at “Santa Rita de Castilla,” where they catalogue their experiences. The priests also use the website to draw the public's attention to hot-button issues like pollution. Blogging about politically sensitive issues can be risky, however, and Cadenas and Berjon suspect both the government and the region's oil companies of putting them under surveillance. They say they have received several threats, too.

Writing on the blog “Toustodo,” Oscar Muñiz asks why governments always seek to bury information about such disasters, when it's their obligation to do just the opposite.

Un país serio y responsable no deja a la deriva los informes que seguramente se encuentran encajonados en los escritorios de la alta burocracia; un país con talante encara con seriedad y responsabilidad los problemas que se repiten mes a mes, año tras año.

A serious and responsible country does not just allow reports to gather dust in the drawers of the upper echelons of the bureaucracy; a determined country confronts, in a serious and responsible manner, the problems that recur month after month, year after year.

Writing on Lucidez.pe, political scientist Juan Pablo Sánchez Montenegro also addressed the Northern Peru pipeline spill:

Se trata de que el viejo oleoducto de cuarenta años aún no ha sido adecuado a las normas jurídicas y técnicas vigentes que prohíben que exista bajo el agua tuberías destinadas al transporte crudo. La empresa estatal, a través de su representante Víctor Mena, se ha limitado a culpar a la geografía de la zona por los desastres ocasionados.

This is about a 40-year-old pipeline that still does not meet current legal and technical standards, which prohibit the use of pipes to transport crude through waterways. The state-owned company, says representative Víctor Mena, has confined itself to blaming the disasters on the region's geography.

On July 22, Miguel Donayre Pinedo republished on his blog a report by the priests mentioned above, Berjón and Cadenas:

Un comunero entró en la quebrada y, con ojos espantados, vio cantidad de peces y boas muertas y manchas de petróleo por todos lados. Se ha quebrado el oleoducto en la zona que los comuneros denomina Varillal (atención para los ambientalistas). Asustado regresa a la comunidad y conversan entre autoridades y comunidad. […] Hasta el 2 de julio sólo había llegado 5 litros de agua por familia y agua del Marañón. De nuevo, las emergencias no son atendidas, menos si es lejos de la ciudad. Los planes de emergencia o no existen o no funcionan. Quien sí acude, dicen los pobladores, es Petroperú llevando personal sanitario, entre ellos un doctor. Échense a temblar.

A local man entered the gorge and was horrified to see the amount of dead fish and snakes and oil slicks everywhere. The pipeline broke in a region that locals call Varillal (attention: any environmentalists). Frightened, the man returns to his village, where discussions are held between state authorities and the community. […] By July 2, only five liters of water have arrived for each family, and the water is from the [contaminated] Marañón river. Once again, we find, emergencies are ignored, especially when they are far from the cities. Emergency response plans either don't exist or they don't function. The only ones to show up, locals say, are Petroperú's medical personnel, including a doctor. Now's the time to start being afraid.

Pinedo enumerates several of his own points about the possible longterm consequences of the new spills in the Amazon.

1. Con la vaciante del río que se produce a fines de junio 2014, como todos los años, comienza a salir el pescado de las cochas y a migrar río arriba: “mijano”. ¿Surcará este año el mijano? Sospechamos que no. Se produce una barrera biológica. ¿Cuál será el comportamiento del pescado? […] 3. El impacto económico en la comunidad de Cuninico será terrible. ¿De qué van a vivir todos estos pescadores? Cuando una empresa rescinde el contrato a un trabajador tiene que pagar unos derechos. ¿Quién paga los trabajos que estos pescadores no van a poder realizar?

1. As water levels in the river decrease at the end of June 2014, as they do every year, the fish start to come out of their pools and migrate up river: the “Mijano” [annual migration]. Will the fish make it upstream this year? We suspect not. A biological barrier has been produced. How will this affect the fish's behavior? […] 3. The economic impact in Cuninico will be terrible. How will the fishermen survive? When a company terminates a worker's contract, they have to compensate them. Who is going to pay for the work the fishermen have lost?

Meanwhile, the investigation into the spills’ causes continues, as does the practice of hiring of minors for cleanup. Allegedly, the government is still considering levying ;sanctions against Petroperú. Declearing a state of emergency in the affected area is also up for debate.

OEFA envía tercer equipo de supervisión por derrame de petróleo en Loreto ⇢ http://t.co/U0u97mDSsY pic.twitter.com/E6R4LgCZNS

— Agencia Andina (@Agencia_Andina) July 21, 2014

The OEFA [Peru's environmental oversight agency] is dispatching a third team to supervise the oil spill [investigation] in Loreto.

1 comment