Slave labour is a remnant of the times of slavery in Brazil, particularly in the Northern and North-eastern States, and this is a well known fact. As the last country in the world to abolish slavery, only in 1888, temporary slavery due to indebtedness and forced labour has continued and been combated regularly by Government in isolated regions, where the arms of the justice system face a demographic challenge.

However, every time there is this type of incident in the State of São Paulo, particularly in Greater São Paulo, the news makes the front pages of the main Brazilian newspapers. That’s what happened last week, when labour auditors from São Paulo, accompanied by labour prosecutors, freed 20 people from slavery (two of them under-age, at only 17 years old) in Mogi Guaçu Municipality (SP). Sakamoto's Blog [pt], specializing on slave labour news and a partner of the prize winning Reporter Brasil website [pt], reported the incident, drawing attention to the irony of there being adolescent slaves living in an abandoned state school.

OK, isso já aconteceu outras centenas de vezes no Brasil, infelizmente. O absurdo da vez foi que o empregador alojou o pessoal em uma escola pública desativada, com fiação elétrica exposta e esgoto correndo a céu aberto. Mesmo depositando o pessoal nessas condições, disse que cobraria aluguel pela hospedagem.

A prefeitura havia feito um contrato com Pimenta para que ele usasse a casa dos fundos da escola em troca de manutenção do local. A escola Fazenda Graminha foi cedida pelo Estado para o município há nove anos. Agora, o contrato será cancelado e a prefeitura estuda entrar com um processo contra o empregador. O prédio foi lacrado e a secretaria fará um estudo sobre a possibilidade de reativar a escola. Incrível! Discute-se a “possibilidade”…

The town hall had set up a contract with Pimenta for him to use the house behind the Municipal School in exchange for carrying out the maintenance of the place. Graminha Farm School was assigned to the Municipality, by the State, nine years ago. Now, the contract will be cancelled and the town hall is analysing whether to sue the employer. The building was closed off and the secretariat will carry out a study on the possibility of reopening the school. Incredible! They are still discussing the “possibility”…

Sugarcane cutters having lunch in the middle of the plantation, under a scalding sun. Meals served with no tableware, no protection against the elements. Photo: Ricardo Funari

The incidence of slave labour in São Paulo evokes the issue as discussed in the past by the independent journalist and intellectual from Pará State Lucio Flávio Costa: Is slave labour an Amazonic anomaly? [pt]

Desde 2003, 192 pessoas foram autuadas pelo Ministério do Trabalho e Emprego por submeter seus empregados a regime de trabalho análogo à escravidão. Mais de dois terços dessas empresas (147) atuam na Amazônia Legal. O campeão nacional do trabalho escravo é o Pará, com quase um quarto de todas as atuações, 52. As duas colocações seguintes nesse nefando ranking são ocupadas por Estados amazônicos: Tocantins (43) e Maranhão (32).

O que leva à concentração dos casos de exploração de mão-de-obra não é uma anomalia amazônica, mas o fato de a região constituir a área de expansão da fronteira econômica do Brasil. Há o pressuposto tácito (ou tático) de que o pioneiro não traz necessariamente consigo a contemporaneidade.

What leads to a high concentration of labour exploitation is not an Amazonian anomaly, but the fact that the region is an area of the expansion of the economic frontier of Brazil. There is a tacit assumption that the pioneer does not necessarily bring with him contemporary habits.

What Lucio Flávio Pinto means is that despite the higher incidence of slave labour in the frontier States, due to favourable conditions (besides geographical ones, according to him, also the absence of contemporary practices, justice, education etc.), it is carried out by economic agents, farmers and businessmen, from all parts of Brazil, always aligned with local agents. That is to say: “the circumstances make the thief” (a Brazilian popular saying) and in various favourable contexts for the exploitation of labour, the Brazilan heritage of slavery manifests itself again. Outside the frontier, other factors contribute to the incidence of the phenomena, such as: bad local administration, scarce auditing, weak trade unions, migrant labour, a more vulnerable and misinformed population.

Sugarcane cutters in the lodgement: no potable water, no beds, no electrical light, no kitchen facilities or restrooms. Photo by Ricardo Funari.

The Mogi-Guaçu case is not isolated and Brazilian bloggers have been reporting regularly on the incidence of slave labour in São Paulo, in both rural and urban areas. This year, the Anjos e Guerreiros [pt] blog posted an article about flagrant slave labour and the exploitation of child-labour on a lemon farm in Cabreúva Municipality, 70 kilometres from São Paulo City.

Uma denúncia levou a polícia até a fazenda. Um lavrador estava na propriedade há quatro meses e conta que não recebeu nenhum pagamento. Os responsáveis pela contratação devem responder por exploração de trabalho infantil.

– Às vezes o povo dá um pouco de comida. Tem vez que nós não comemos, não almoçamos e nem jantamos.

Os funcionários contaram para os policiais que havia crianças trabalhando na colheita de limão. O Conselho Tutelar foi chamado e flagrou seis menores trabalhando no local. Um deles, um menino de 12 anos.

– Não tem luvas nem tinha equipamento, nem água. Eu ganho R$ 2 reais – diz o menino.

Uma adolescente conta que os patrões pediram para todos fugirem assim que ficaram sabendo que a polícia ia chegar.

– Nós dissemos que não fugiríamos – afirmou

– Sometimes they give us a little bit of food. Sometimes we don’t eat, don’t have lunch or dinner.

The workers told the police there were children working on the lemon harvest.

The Tutorial Council was called and witnessed six minors working in the farm. One of them was a boy of 12 years old.

– There are no gloves and there was no equipment, not even water. I earn R$2 reais – said the boy [around $ 1].

One adolescent tells that the employers told them all to run away as soon as they heard that the police were going to arrive.

– We told them we would not run away – he stated.

In São Paulo City, in the heart of the urban area, the incidence of slave labour has other characteristics to which the Verdefato blog [pt] draws our attention:

O trabalho escravo urbano é menor se comparado ao do meio rural. A Polícia Federal, as Delegacias Regionais do Trabalho, o Ministério Público do Trabalho e o Ministério Público Federal já agem sobre o problema. Vale lembrar que a escravidão urbana é de outra natureza, com características próprias…O principal caso de escravidão urbana no Brasil é a dos imigrantes ilegais latino-americanos – com maior incidência para os bolivianos – nas oficinas de costura da região metropolitana de São Paulo. A solução passa pela regularização da situação desses imigrantes e a descriminalização de seu trabalho no Brasil.

A hooded informant who succeeded in escaping from the estate (in the background) takes the Brazilian Federal Police to a site where workers are kept imprisoned. Photo: Ricardo Funari

The same blog reports this case of a Bolivian immigrant, one of many working on these conditions:

Sentada há mais de 16 horas diante da máquina de costura, a mãe de Ramón tem pressa. Maria Diaz costura uma peça de roupa atrás da outra, intensamente. Ela tem uma agenda para cumprir. Só pára quando precisa comer ou ir ao banheiro. A mãe do pequeno Ramón é uma mulher exausta.

Desde que chegou ao Brasil, em 2003, trabalha do amanhecer até tarde da noite. Não tem carteira assinada, equipamento de proteção, assistência médica. Ela não existe nos registros de imigração. Oficialmente, o governo brasileiro não sabe de sua presença. Tampouco sua saída da Bolívia, em 2003, foi registrada pelo governo daquele país. Maria foi trazida para São Paulo por intermediários conhecidos como “coiotes”, que ganham dinheiro contrabandeando gente de um país para outro. Em São Paulo, pelo menos 100 mil bolivianos estão nessa situação.

Since she arrived in Brazil, in 2003, she has worked from early to late. She does not have a work permit, protective equipment or medical assistance. She does not exist in the immigration registry. Officially, the Brazilian Government does not know of her presence. Her departure from Bolivia, in 2003, was not registered either. Maria was brought to São Paulo by intermediaries known as “coyotes”, who earn money smuggling people from one country to another. In São Paulo, at least 100,000 Bolivians are in this condition.

A man found imprisoned inside an estate shaves before being photographed for the first work permit he has ever had in his life. Photo by Ricardo Funari.

Still in São Paulo, an article by sociologist and Municipal Assembly member Floriano Pesaro, posted on the Coisas de São Paulo blog [pt], discusses the case of street children forced to work by their parents. It is a case of double infringement: child labour and slave labour:

O trabalho infantil nas ruas, no comércio e até dentro de casa resiste no Brasil urbano e rural. Manifesta-se em suas piores formas, com práticas análogas ao trabalho escravo: exploração sexual comercial, venda e tráfico de crianças para trabalho ou exploração sexual, uso de crianças no comércio de drogas. Estas práticas envolvem atividades criminosas que são ilícitas e que levam crianças e adolescentes à morte. Na cidade de São Paulo, de acordo com pesquisa da FIPE, de 2007, são pouco mais de mil crianças em trabalho infantil somente nas ruas.

Whilst writing this article for Global Voices Online, I wondered if disseminating such bad news to the whole world would not damage Brazil’s image abroad, but this very interesting blog by Edson Rodrigues [pt], helped me make up my mind. He brings a list of 15 Truths and Lies about slave labour in Brazil, one of which has to do with the international dissemination of slave labour practices bringing damage to our country:

12) Mentira: A divulgação internacional prejudica o comércio exterior e vai trazer prejuízo ao país. Verdade: Isso é uma falácia. Não erradicar o trabalho escravo é que prejudica a imagem do Brasil no exterior. As ameaças de restrições comerciais serão levadas a cabo se o país não fizer nada para resolver o problema. Que usamos trabalho escravo, isso é público e notório…A agricultura é fundamental para o desenvolvimento do país. Por isso mesmo, ele deve estar na linha de frente do combate ao trabalho escravo, identificando e isolando os empresários que agem criminalmente. Dessa forma, impede-se que uma atividade econômica inteira venha a ser prejudicada pelo comportamento de alguns poucos.

Making his words my own, I conclude this article feeling sure that slave labour is a generalized remnant of the time of legal slavery in Brazil and that it would be an anomaly not to combat this phenomenon head on.

—

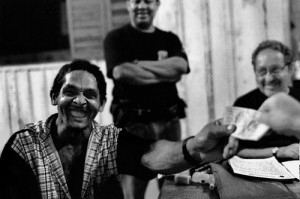

The photos that illustrate this piece have kindly been provided by Rio de Janeiro based photojournalist Ricardo Funari, who works to create and distribute images documenting and addressing issues of social injustice in the country. According to what he has seen through his work, “the main mechanism of enslavement in Brazil is through debt – the physical immobilization of workers on estates until they can pay off debts, which are often incurred through fraud, and are provoked by their very working conditions. Thus workers from areas hit by recession or drought are enticed into verbal contracts, and then loaded into trucks which transport them thousands of miles to work in dangerous conditions. On arrival the attractive wage rates promised to them are reduced, and then forfeited in order to pay for transport costs, food and even working tools. Workers often do not receive cash in hand. As time passes, the workers’ debts become greater and greater so that they have no possibility of leaving.” His photo set, Contemporary Slavery in Brazil, can be seen on his Flickr account.

2 comments

Not doing anything would damage Brazil’s image in the world. Thank you for a good article.

Harm the image of Brazil? Has slaves here man! What can be worse than that? Regrettable.