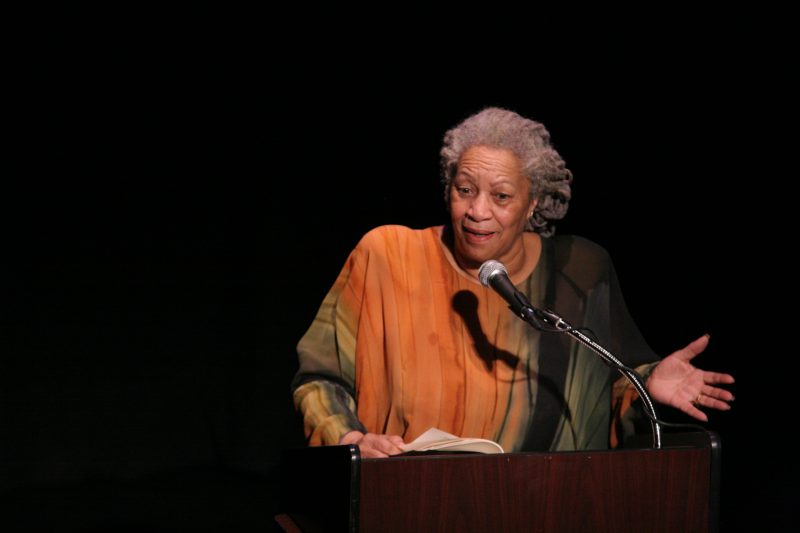

Toni Morrison speaking at a tribute to Nigerian author Chinua Achebe at the 50-year anniversary of “Things Fall Apart” in Town Hall, New York, February 26, 2008. Image by Angela Radulescu, via Flickr: CC BY-SA 2.0.

Toni Morrison, the trailblazing American author, died August 5, 2019, “following a short illness,” according to a statement by her family. Morrison was born 88 years ago in Lorain, Ohio, United States:

We are profoundly sad to report that Toni Morrison has died at the age of eighty-eight.

“We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”

February 18, 1931 – August 5, 2019 pic.twitter.com/DWnElCpMKc

— Alfred A. Knopf (@AAKnopf) August 6, 2019

Morrison was a groundbreaking author who understood the power of language as “an oppressive or uplifting force —she refused to let her words be marginalized.” Her books were written from the perspective of the minority and powerless—a black African American.

Morrison not only mentored many generations of African American writers — but she also inspired many Nigerian writers who met her in her books. In 2008, Morrison spoke at a PEN America tribute to iconic Nigerian author, Chinua Achebe, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of “Things Fall Apart.”

Like Achebe, Morrison interrogated issues of race and power in her novels. Nigerian literati remember Morrison for the profound impact she had on West African writing and publishing.

Over a sixty-year writing career, Toni Morrison published eleven novels, five children’s books, two plays, a song cycle and an opera. Some of her literary canons include: “The Bluest Eye” (1970), “Sula” (1973), “Song of Solomon” (1977), “Tar Baby” (1981), “Beloved” (1987), “Jazz” (1992), “Paradise” (1997), “Home” (2012) and “God Help the Child” (2015). Morrison also taught literature as a professor at Princeton University.

In the 1970s, Morrison was “largely ignored as a writer” but the next decade heralded the acknowledgment of her work with many awards. Morrison's novel “Beloved” won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize Winner in Fiction. The first African American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993, Morrison's novels were “characterized by visionary force and poetic import [that] gives life to an essential aspect of American reality.”

United States President Barack Obama awarded Morrison the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012.

‘Toni reaches us deeply, using a tone that is lyrical, precise, distinct, and inclusive.’ — President Obama gave Toni Morrison the ultimate tribute while awarding her the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012. Morrison died today at 88. pic.twitter.com/1XGe8Fs73e

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) August 6, 2019

Nigerian writers mourn a totem

Ayodele Olofintuade Nigerian writer celebrates an ancestor who has now being deified:

Toni Morrison joined the ancestors, she lived a worthy life, a full one. Mà j'ọ́ọ́kún, mà j'ekólò, oun tì wọ̀n njẹ l'àjúlè ọ́run ni kò bá wọn jẹ.

— ayodele olofintuade (@aeolofintuade) August 6, 2019

Toni Morrison joined the ancestors, she lived a worthy life, a full one. Do not eat slugs, turn down offers of worm, feast at the table of the Irúnmolè [deity], of the Óósa [god].

Morrison cannot die, exclaimed visual artist Victor Ehikhamenor:

When you are Toni Morrison, you don’t die, you never die. She birthed eternity with the canonical works she created. Let the world not mourn by crying their bluest eyes out for one of our most beloved! ??

— victor ehikhamenor (@victorsozaboy) August 6, 2019

Nze Slyva Ifedigbo was full of gratitude:

Thank you for the stories.

Rest in peace. #ToniMorrison pic.twitter.com/FWnDX3oPS3— Sylva Nze Ifedigbo (@nzesylva) August 6, 2019

Writer Ukamaka Olisakwe prayed for the eternal repose of Morrison's soul [Ka mkpulu obi gi naa na ndokwa]:

Sleep well, Toni Morrison. Ka mkpulu obi gi naa na ndokwa.

— Ukamaka Olisakwe (@MsOlisakwe) August 6, 2019

She called us—at the margin of society—”beloved,” wrote poet Gbenga Adesina:

Toni Morrison solved the problem of Naipaul for me. Born a year apart, both at the margin of society. Naipaul internalized the colonial shame & wrote great sentences in service of cruelty. Toni insisted on that margin as a place of insight & subjectivity, she called us beloved.

— Gbenga Adesina (@Gbadenaija) August 6, 2019

Ike Anya bid a safe journey [ije oma] to the lion [agu]:

Ije oma, agu https://t.co/IommMZTfyl

— Ike Anya (@ikeanya) August 6, 2019

Morrison as a guest lecturer at the US Military Academy, March 28, 2013. US Army photo by Mike Strasser/USMA PAO via Flickr: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Morrison made ‘words sing in your heart even though your head does not understand it’

Writer Temitayo Olofinlua, from Ibadan, Nigeria, narrates that she read “Beloved” at university but did not understand it at first until her lecturer discussed it in such a way that made the author think the professor was talking about another book and decided to read it over again:

It is the way that Morrison wields language that makes her unforgettable. She makes words sing in your heart even though your head does not understand it yet. However, after your heart has sung the lines, again and again, your head gets it. And with that language, she wrote about the struggles of African Americans in America.

Morrison wrote about what it means to be African American in a way that even I, a young Nigerian student at the time, connected with the experiences. Her stories were human enough for me to relate with. That is why Morrison's novels remain even more relevant today, as they were decades ago when she wrote them. This transcendental power of writing is what Morrison possesses, this ability to speak through her words, making the works echo through times, that is what makes her special. She lives on through her works.

Poet and linguist Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún describes Morrison as a “force” who granted black people an existence in “the world as valid and authentic as others”:

As a black woman writing in the world, and one who decidedly chose a spot far away from the mainstream and made it hers, she was always a force for all the world. In her books, black people and black women all over the world have come to find their way of existing in the world as valid and authentic as others’.

…I will remember her with these memorable lines from her Nobel lecture: ‘We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives…’ and more profoundly, ‘Language alone protects us from the scariness of things with no names. Language alone is meditation.’ For this, and for her work as a strong forebear, I will cherish her memory and the challenge she has left for us.

The ‘black woman writer’

In an interview with the Paris Review, Morrison — who ordinarily abhorred labels — made an exception and embraced the title “black woman writer.” She admitted that her work as a writer is to make “meaning out in the world” in response to the “incredible violence” and “willful ignorance” she witnessed throughout her lifetime:

It is not possible for me to be unaware of the incredible violence, the willful ignorance, the hunger for other people’s pain. I’m always conscious of that, though I am less aware of it under certain circumstances. … What makes me feel as though I belong here — out in this world — is not the teacher, not the mother, not the lover, but what goes on in my mind when I am writing.

Then, I belong here and then, all of the things that are disparate and irreconcilable can be useful. Struggling through the work is extremely important—more important to me than publishing it.