São Tomé and Príncipe, like other islands in the Gulf of Guinea such as Bioko and Pagalu, is one of the countries on the West African coast that stands out when the issue at hand is biodiversity. For this reason, since the end of the 19th century these “beautiful equatorial islands” have attracted enormous interest from international researchers [pt].

Their forests have been classified by the international organisation WWF as one of the two hundred most important areas in the world in terms of biodiversity. They are the habitat for around 25 species of endemic birds, an extraordinary number and comparable [pt] to the “Galapagos Archipelago (22 species), which is eight times larger than São Tomé and Príncipe, and more than double the number of the Seychelles (11 species), which are slightly smaller than São Tomé and Príncipe”.

The Olive Sunbird – Cyanomitra olivacea. Photo from the blog Apenas a Minha História (used with permission)

In the nineties, Birdlife International included the São Tomé and Príncipe forests in Africa's “Important Bird Areas (IBAs)“, located in the top 25% of the 218 “Endemic Bird Area (EBAs)” in the world.

Making the country a world reference for birds [pt], which are unarguably the most obvious representatives of the immense biological wealth, the islands have been a constant cause for celebration and appreciation, as is the case in the newspaper Jornal Quercus Ambiente [pt], where Martim Pinheiro de Melo affirmed in an article:

As ilhas de São Tomé e Príncipe no Golfo da Guiné teriam certamente fascinado Darwin se ele por lá tivesse passado.

The São Tomé and Príncipe islands in the Gulf of Guinea would have definitely fascinated Darwin if he had gone there.

It was precisely in search of the allure, magic and splendour which the “beautiful equatorial islands” offer visitors with open arms that Portuguese biologist João Pedro Pio went to southwestern São Tomé in July 2012 [pt], to Ribeira Peixe to be exact. His intention was to find birds (the Island Bronze-naped Pigeon, São Tomé Green Pigeon and Maroon Pigeon) and other rare species in danger of extinction, as is the case for the Ibis, which is at the top of the list [pt] as one of the critically endangered endemic birds.

The blog Apenas a minha história [pt], where João Pedro relates his experiences over the course of a year as a foreigner and researcher in São Tomé, describes the scene of devastation he found in the area where it should have still been possible to see the birds:

Bem, quando o transecto começou, numa zona que anteriormente seria floresta cerrada, agora era um descampado enlameado. Já não haviam árvores nenhumas! Foram todas cortadas indiscriminadamente (…) com a excepção de um ou outro Viru-vermelho que permanecia comicamente sozinho no meio de toda aquela destruição, não havia uma única árvore de pé.

Well, when the transect started, in an area that used to be closed forest, it became a muddy clearing. There were already no trees at all! They had all been cut down indiscriminately (…) with the exception of one or two Viru-vermelho remaining comically alone in the middle of all that destruction, there wasn't a single tree standing.

“In the distance a bulldozer works ruthlessly while the whole landscape seems to cry at the destruction.” (Image used with permission.)

Ribeira Peixe, also called Emolve [pt] (after the vegetable oil company), was a large semi-abandoned oil palm plantation, a monoculture that always presented a danger to the island's biodiversity, a danger aggravated above all by the threat to go ahead with plans to rehabilitate and expand the plantation from the current 610 hectares to approximately 5,000 hectares, a fact confirmed [pt] in 2009 when the São Tomean State signed an agreement with Belgian company SOCFINCO for palm oil operation.

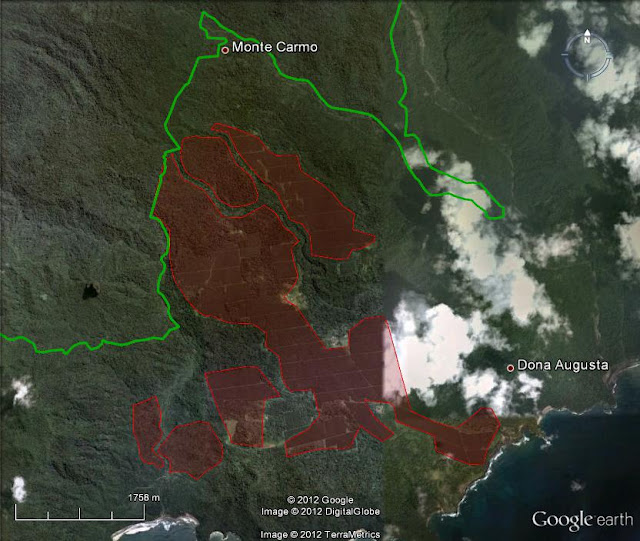

João Pedro created the following map of the area:

“The green line marks the border with the Obô National Park. The whole red area is old palm plantation or forest that I have already seen has been cut down. As you can see, there is a lot of forest that used to stand together with the Emolve palms and has now been lost…”

The young researcher wrote that “the Government decided that it would be more profitable for the country to swap all its biodiversity, which is unique in the world, for a few tons of oil”:

O governo de São Tomé e Príncipe assinou um contrato com a Agripalma, cedendo-lhes 5000 ha, ou seja, terra suficiente para que o negócio de venda de óleo de palma se torne rentável. (…) E como se o Ibis e as outras aves endémicas presentes na zona não fossem suficientes para parar o abate descontrolado de árvores, é aqui que se pode observar o fantástico Pico do Cão Grande que, só por si, poderia e devia ser explorado como um foco de atracção turística importantíssimo para São Tomé e Príncipe! Mas não (…)

The São Tomé and Príncipe Government signed a contract with Agripalma giving them 5000 ha, in other words, enough land so that the business of selling palm oil would become cost-effective. (…) And as if the Ibis and other endemic birds in the area were not enough reason to stop the uncontrolled logging, it is here that the fantastic Pico do Cão Grande [Great Dog Peak] mountain can be seen by itself; it could and should be explored as an important tourist attraction for São Tomé and Príncipe! But no (…)

The former International Coordenator of the World Rainforest Movement, Ricardo Carerre [es], in the report titled “Oil palm in Africa: Past, present and future scenarios” explains the processes that led to the 50 – 75 [pt – both links] million dollar deal in exchange for priceless riches.

São Tomé and Príncipe is one of the signatories of the Convention on Biological Diversity and has committed to finding solutions for the preservation of biodiversity. However, citizens and Internet users alike ask themselves if perhaps a study or evaluation has been carried out by a qualified entity on the environmental impact that this monoculture system will have in both the short and long term.

The palm oil may be used for the production of “biofuel” for commercial purposes, but these palm plantations aggressively degrade the environment, absorbing the soil's nutrients and leaving it extremely poor until, in less than two decades, it becomes totally barren land, serving only for scrub growth, which is perfect fuel for fires. Furthermore, the factories that emerge to process this oil typically produce a large amount of contaminating waste, represented by husks, water and fat residues and, as it is presumably a monoculture, it will need a large amount of herbicides, fertilizers and pesticides.

There is the saying “learn from others’ mistakes”, and the benefit of history is that we can learn to not make the same mistake. In Indonesia and Malaysia, for example, entire forests have disappeared with palm oil operations, as if they had never even existed. Close to two million hectares of forest are destroyed annually and the exploitation in question only seems to benefit large farming operations and corrupt governments, the weakest can only look the other way, an occurrence that has been spreading in other developing regions in the world.

6 comments