Spartak Subbota (right) and Yevhen Yanovych at the Podcast Therapy show. Screenshot from YouTube.

A new scandal in Ukraine caused a wider discussion on the failures of the university education system and media responsibilities.

The result of a journalistic investigation on Spartak Subbota, published on April 11, 2023, in a youth media outlet, was devastating: over 153,000 words and about five hours of the film proved in great detail that the celebrity had faked his biography and credentials.

Spartak Subbota, 31, has been promoting himself in Ukraine as a scientist, doctor, and psychology guru since 2017. He was a co-host of a popular podcast on psychology called Podcast Therapy, which drew up to a million online views on YouTube.

The 70-minute podcast was designed as a conversation between two friends and was hosted by professional comic actor Yevhen Yanovych. The episodes mostly consisted of Yanovych reading questions to Subbota from viewers seeking advice. It was launched in early 2022 and had 86 episodes altogether, with an average of 500,000 views per episode by the beginning of April 2023.

Spartak's rising

Subbota claimed he had studied to be a psychiatrist — a degree which only medical schools can grant in Ukraine. According to the author of the investigation, psychotherapist Illya Poludyonny, Subbota never studied in a medical university. Instead, he got a degree as a psychologist in a non-medical university, meaning, that he did not have the skills and credentials for medical treatment of people.

A psychology degree takes 5 years, and reports indicate Subbota started studying in 2009. However, he insisted that he started to study medicine at 15, as it takes about eight years to become a psychiatrist. In 2017, at the age of 25, Subbota was pretending to hold a Ph.D.

This was the weakest point of the story he apparently invented. Subbota was free to spread lies about his university education because, in Ukraine, this information is considered private. A university or any other state body cannot share education-related information with a third party. But information about dissertation defenses, as well as dissertation texts, are public. And according to public data, Subbota defended his dissertation in 2022.

Subbota's story is indicative of a much larger issue. In Ukraine, university degrees are seen as a status symbol essential for getting or maintaining a certain social status. For this reason, the entire system of university education is riddled with scandals and problems. Two subsequent ministers of education and science of Ukraine were accused of plagiarism, with no consequences to them nor to the people and institutions responsible for awarding them with the Ukrainian analog of the Ph.D. degree. The demand for Ph.D. candidates in Ukraine is higher than in many other countries, but the quality of submitted work is often notoriously low.

In his investigation, Poludyonny stumbled upon a complicated network that helps people fraudulently obtain Ph.D.s in psychology. In the case of Subbota and several other candidates, the required foreign research publications were actually published by a set of Ukrainian journals registered under virtual addresses in the United States and the UK, all connected to Subbota's academic supervisor.

In addition, it appeared that Spartak was a false name that he adopted after he graduated from university — a good way to protect the information about his education if someone were to go searching.

The muscular, heavily tattooed psychologist started gaining prominence in 2019, masterfully increasing his presence in the media. In three years, his work led him from the biggest Ukrainian online media to nationwide TV shows and the New Yorker website, all featuring or citing him as an expert. A publishing house in Ukraine whose mission is to promote Ukrainian scholars popularising science published and republished a book by Subbota several times and was preparing the publication of the second one.

But, most seriously, Subbota converted his popularity into demand for his services as a psychotherapist. Some female clients of his later complained to Poludyonny of unprofessional and abusive treatment, where he pursued sexual relationships with them and caused additional trauma for the young women.

Following a rich legacy of scammers

The denunciation caused a storm on Ukrainian social media, with many users celebrating Subbota's fall and the excellent investigative work. Others tried to defend Subbota in the comments, pointing to Poludyonny's conflict of interest as a fellow psychologist – theoretically, Subbota's competitor - and the helpfulness of the information Subbota provided via his podcast. Interestingly, it appeared that the majority of Subbota's listeners and viewers were teenagers.

The podcast, which made Subbota famous among the Ukrainian youth, appeared at just the right time. In 2019, clinical psychologist Julie Smith launched a TikTok channel called Dr. Julie, offering short clips with mental health advice. It was especially in demand during the COVID-19 pandemic; by 2023, its audience had grown to about 4.5 million viewers. In early 2022, Smith also published a book. Smith's social media popularity made it a must-read, with over 7,500 reviews on Amazon and over 14,300 votes on the book recommendation site Goodreads.

In Ukraine, however, Subbota had other predecessors, post-Soviet style. In 1989, Anatoly Kashpirovsky, a Ukrainian-born psychotherapist, started to present his “health show” on Moscow's central (still Soviet back then) TV station, claiming to have the power to heal people from their screens.

With the entire Soviet Union and then-post-Soviet space gazing at their TV sets in anticipation of a miracle, these performances propelled Kashpirovsky to a seat in the Russian parliament in the early 1990s. He left Russia then, reportedly to offer his unique abilities — it was believed that he was proficient in hypnosis — to Soviet emigrants in the US and Israel, but he came back in the 2010s.

Kashpirovsky's example was followed by various healers, paranormalists, astrologists, and even one messiah offering to help the Soviet people, ignorant and starving for spiritual practices after seven decades of the Soviet war on religions and any public exercises of faith or superstitions.

Invitation to “paranormalists and folk healers” to apply for “methodical literature” in Moscow “for increasing effectiveness of your work.” From a local newspaper in Donetsk, USSR / Ukraine, 1990. Scan copy by Yulia Abibok, fair use.

In the early 1990s, a woman in Donetsk, Ukraine, a journalist by training and herself a recent Communist activist, and her husband proclaimed she was a reincarnation of both the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ sent to people with a special mission before the Day of Judgement of November 24, 1993.

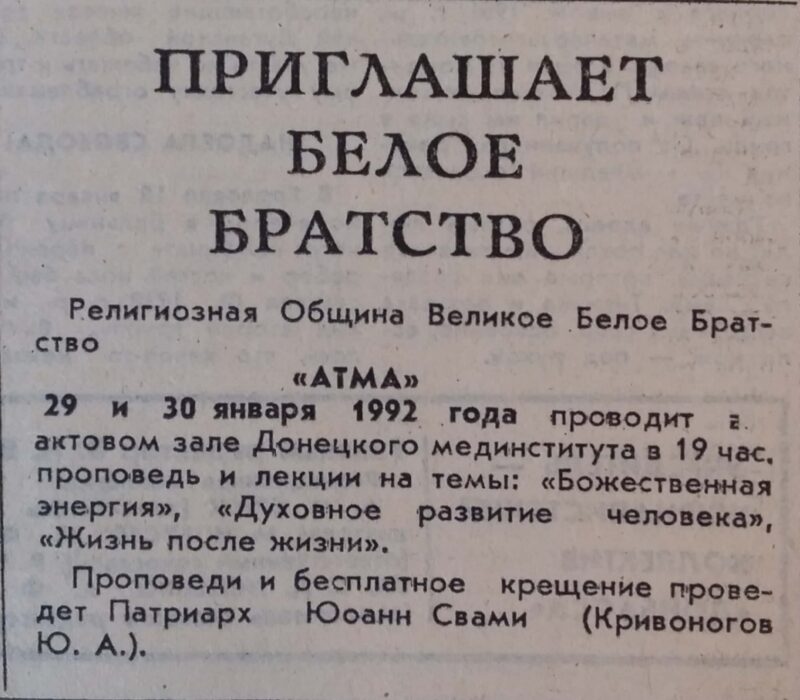

Announcement of a “sermon and lectures” by Yuri Krivonogov, the White Brotherhood leader and the husband of “Maria Devi Christos,” in Donetsk, Ukraine, in 1992. Despite reporting about terrifying consequences of the White Brotherhood activities, the same media outlets continued advertising the sect. Scan copy from a local newspaper by Yulia Abibok, fair use.

White Brotherhood, the totalitarian sect they created, attracted thousands in Ukraine and Russia, mostly teenagers, as it was claimed in newspapers of that time. In Ukraine, the activities of “Maria Devi Christos” and her husband were stopped on the “Day of Judgement” when the police prevented the sect followers from committing mass suicide in Kyiv.

The leaders of the sect were arrested and sentenced. Several years after the end of her prison term, “Maria Devi Christos” emigrated to Russia and, after several years, recreated her sect, but with no visible influence anymore.

In Ukraine, however, another man with “supernatural abilities” gained prominence right around the time when Kashpirovsky started to regain his success in Russia. Andriy Slyusarchuk was nicknamed “Doctor Pi” for his advertised ability to memorize up to one million characters of the mathematical constant pi. He participated in several TV shows demonstrating unusual tricks of his memory — later proved to be staged and faked.

Like Kashpirovsky, Slyusarchuk was believed to be a strong hypnotist. Like Subbota, he changed and faked his biographical details, making them difficult to check. He also claimed to be a doctor with a doctoral degree who enrolled in a university in Moscow at the age of 12. It appeared, that he had never studied in any university.

What was striking in Slyusarchuk's case was that he managed to confirm his credentials in Ukraine, got positions in universities, enjoyed praise from Ukrainian high-ranking officials, including two subsequent presidents, and carried out medical procedures as a neurologist, neurosurgeon, and psychotherapist, with some reported grave and lethal consequences.

Like Subbota's case, it was a journalistic investigation that put an end to Slyusarchuk's activities and led to his detention in 2012.

Yet another cataclysm

Experts say that calamities like the fall of the Soviet Union, the COVID-19 pandemic, or the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which resonated in the entire world, make affected societies especially vulnerable to scams. Cases like Subbota's could happen at any time but are most probable in times of high uncertainty.

“Today, Ukrainian society needs support, anything or anyone to rely on. This leads to people perceiving information less critically and looking for folk healers, horoscopes, kashpirovskys. And this is fertile ground for various swindlers, especially when they are self-confident and charismatic,” Iryna Eihelson, a social psychologist, said in an interview with Global Voices.

Vadym Vasiutynskyi, a psychology professor, added that, at all times and in each society, people need a leader, a small percentage of them — literally someone to lead them. Leaders are usually self-confident, charismatic, and narcissistic, and often attractive, middle-aged men, as people still tend to take men's words more seriously.

In war-torn Ukraine in 2022 only, this was proved several times. The beginning of the Russian full-scale invasion led to the immediate and enormous popularity of Oleksiy Arestovych, a professional adventurist and populist who managed to successfully play down the emerging panic. For several months, the Ukrainian public carefully listened to his regular statements as a presidential office representative: a mix of truth, half-truth, and comforting lies, until it became obvious that Arestovych was not reliable.

The next fallen idol was writer Andrey Vasilyev known as Dorje Batuu, a former Russian citizen who emigrated to Ukraine in the early 2000s and then to the United States. A historian by education and an experienced journalist, for several years, he claimed to be an engineer working at NASA. He published several fiction books describing with humor his experiences at that work.

An initially innocent artistic image became harmful when Vasilyev-Batuu started to pose as an expert consulting US military officials on war-related Ukrainian issues and once spreading misinformation about the origin of a rocket that hit a Polish territory close to the Ukrainian border, killing a man there. In late 2022, a Ukrainian blogger and soldier Victor Tregubov checked and reported that Vasilyev has never worked for NASA.

Both Arestovych and Dorje Batuu still have fans in Ukraine, however. There is a chance that Subbota could preserve some supporters as well. In his case, apart from the war-related anxiety, it was the usual tendency of teenagers to look for role models and idols which led to Subbota's popularity, according to Vasiutynskyi.

The damage Subbota caused, however, might be bigger. Apart from the reputation of Ukrainian academia and media outlets, which referenced him as an expert, his teenage followers he duped and Yevhen Yanovych, Subbota's podcast fellow, who was apparently fooled and had to apologize publicly, the general trust in psychologists is at stake when more and more people need professional help, Eihelson told Global Voices, referencing the ongoing discussions among her colleagues.