[1]

[1]The written script of the word “horse” was different among major states during the “Warring States Period [2]” before Qin standardized them under small seal script. Public domain image.

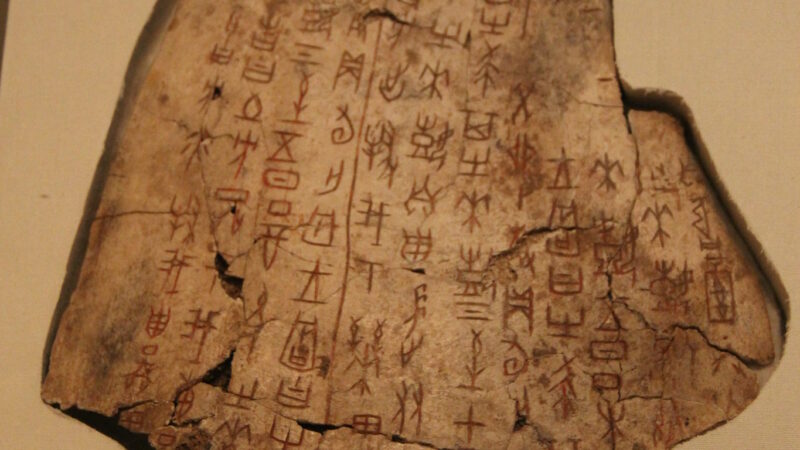

April 20 is the United Nations Chinese Language Day [3]. The date marks the sixth Chinese solar term “Guyu” (穀雨), which is celebrated to honour Cangjie (倉頡), a legendary figure who invented the written form of the Chinese language under the Yellow Emporer [4] (2697–2597), one of the five ancient Chinese tribes. What Cangjie invented is believed to be the oracle bone script [5], which is used for the purpose of divination.

Canjie’s story, however, is just a romanticized version of the origin of today’s written Chinese language. The standardization of written Chinese has been a brutal process that is somehow at odds with the value of “multilingualism and cultural diversity” [6] promoted by the UN’s Language Day.

The standardization of the Chinese texts

The standardization of written Chinese began under Qin Shi Huang [7], the first emperor of a unified middle kingdom of the Qin Dynasty [8]. Confucian scholars and historians in other dynasties usually depicted Qin Shi Huang as a brutal tyrant who was obsessed with the elixir of life and haunted by the fear of assassination.

[9]

[9]Chinese Oracle Bone Script. Public domain photo from Flickr user Gary Todd [9].

After Qin conquered six other states, Qin Shi Huang consolidated the unified kingdom by setting up a hierarchy of officials centring around the emperor, expanding military power through a hierarchical ranking system and mandatory military services, embracing “legalism” — a philosophy of exercising control over his subjects through stern law and punishment, burning of books and burying of scholars [10], building the Great Wall and etc.

The standardization of written Chinese texts, along with currency and units of measurement, were significant steps for Qin Shi Huang’s centralization of power. The first emperor appointed his prime minister Li Si [11]to standardize the written Chinese texts by promulgating the Small Seal Script as the imperial state’s official language (see the top image). The six other major scripts were suppressed or banned. One of the major dictionaries compiled under Li Si’s supervision was Cangjie Pian.

Since Qin, an official and unified written Chinese script has become a most significant political means for the governance of the middle kingdom. Even during Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), when the last middle kingdom empire was under the rule of Manchus [12], a native group of people from northeast Asia who are ethnically distinctive from Han Chinese, the imperial court was eager to standardize the written Chinese texts. In fact, the most authoritative dictionary of Chinese characters, the Kangxi Dictionary [13], was compiled under the order of the Qing Emperor Kangxi. Westerners invented the English term “Mandarin,” which means “officials of the Manchus” (滿大人), to refer to the official dialect used in the Qing imperial court.

China has always been ethnically diverse, and many emperors and royal families, such as Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty and Manchus-led Qing Dynasty, were not Han Chinese. Although written Chinese was standardized and the imperial courts had their own official tongue, outside the courts, the medium of instruction in education was regional mother tongues [14]. Indigenous languages and Chinese languages and dialects were hence able to be preserved locally during the imperial era.

The Kangxi Dictionary [13] also captures the diversity of spoken Chinese languages by providing each Chinese character's pronunciations of major regional languages. This helps many Chinese languages and dialects to find their written matches. That’s why Chinese regional languages, such as Cantonese and Min Nan, have developed their own written forms with expressions very much distinctive from Mandarin.

However, in June 1911, the imperial Qing government started introducing Mandarin [15] as a national tongue to modernize the country's education system. But soon after, the Qing Dynasty was overthrown, and the project to introduce a “national language” (國語) was left to the Republic of China (ROC). In 1913, one year after the establishment of ROC, Mandarin was picked as a unified national language, albeit by a rather weak consensus [15].

According to Ethnologue [16], an authentic website that records 7,168 living languages worldwide, China is still the seventh most linguistically diverse country in the world. It has 281 spoken languages, including non-Chinese indigenous languages and Chinese languages and dialects, but 153 are endangered thanks to the country’s language policy.

The suppression of mother tongues

Upon its establishment in 1949, the People's Republic of China (PRC) inherited ROC's official tongue and called it Putonghua. The new regime also simplified the traditional written form into simplified Chinese characters. Chinese was established as an official language in the UN in 1946. At that time, the ROC represented China, and the UN official Chinese referred to traditional Chinese characters. But since 1971, the UN official Chinese became simplified Chinese characters.

After the implementation of compulsory education in 1986, Putonghua was promulgated [17] as the major medium of instruction in schools. By the end of the 1990s, mother tongues were redrawn from primary school education, with the exception of a few autonomous regions, including inner Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet, where the majority of the local population is not Han Chinese.

In 2000, the Standing Committee of the People’s Congress passed the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language Law [18], demanding Putonghua be used in government and public institutions, schools, and TV and radio broadcasting. In addition, the official language’s standard written form be used in textbooks, public documents, product instructions, public displays and signs, etc. As students are forbidden to speak in their mother tongues inside schools, many have lost their ability to speak in their mother tongues.

In recent years, Putonghua has replaced indigenous languages in education and other institutional settings in autonomous regions, including Xinjiang [19], inner Mongolia [20] and Tibet [21].

While China's critics often slam the suppression of non-Han ethnic languages in autonomous regions as “cultural genocide,” Chinese state-funded media outlets rebuked the accusation as a “smear campaign” [22] as Beijing just extended its suppression of mother tongues among Han, according to national law, to other ethnic groups. Even in Hong Kong, Putonghua is replacing Cantonese [23] as the medium of instruction in the Chinese Language Subject in primary and secondary school education. The term “cultural genocide” cannot accurately capture the zeal for the centralization of power since the Qin Dynasty through the standardization of language.

As the UN language days are meant to promote multilingualism and diversity, let’s celebrate Chinese Language Day with a critical mindset.