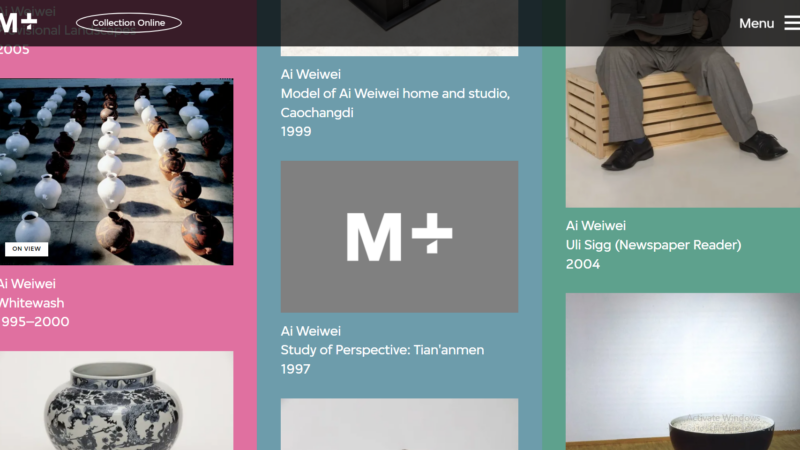

Screenshot of online catalogue of the M+ Museum in Hong Kong, where Ai Weiwei's artwork has been censored. Fair use.

In October 2022, a news article by Bloomberg [1] set off a media frenzy when it suggested that an outdoor screening of the Batman franchise “The Dark Knight” was banned by censors in Hong Kong. It speculated that the decision could be related to the newly enacted National Security Law, but in the end, the actual reason was likely rather undramatic. Due to the movie’s violent content and the venue being outdoor, the Office for Film, Newspaper and Article Administration (OFNAA) recommended that the organiser scrap the screening.

The Hong Kong government was quick to criticise [1] Bloomberg for its misleading reporting. But this penchant for flashy headlines suggesting the imminent threat of Mainland Chinese-style censorship in Hong Kong has distracted from the censoring practices that have already unfolded in the city in recent years.

Following the massive protests against China's encroachment on Hong Kong in 2019 [2], Beijing imposed [3] the National Security Law (NSL) on Hong Kong in June 2020, which defined [4] crimes of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign organisations. While the new legislation primarily targeted politicians of the pro-democratic opposition [5], activists, and critical media outlets [6], it soon also engulfed Hong Kong’s arts and culture scene.

The Hong Kong Arts Development Council (HKADC), established in 1995, has long been instrumental in supporting and funding a wide range of local arts groups, institutions, projects, and even movies. In early 2021, the council was accused [7] by a state-controlled media outlet that it has been funding subversive organisations in the past, especially singling out [8] the film group Ying E Chi, which distributed the protest documentary “Inside the Red Brick Wall,” as well as the Art and Culture Outreach centre that housed [9] Ying E Chi at their arts hub in Foo Tak Building. Since then, the Council has enforced [10] stricter guidelines and measurements to make sure that grant receivers will not be in conflict with national security legislation. Ying E Chi’s previous grant of HKD 700,000 (around USD 90,000) was eventually pulled by the HKADC in July.

In June 2021, the government also passed [11] amendments to the Film Censorship Ordinance with elaborate guidelines regarding the National Security Law. They instruct censors to consider “a film as a whole and its effect on the viewers,” and that they should deem any movie unsuitable for exhibition if it is “likely” to constitute an offence. Soon after, filmmakers in Hong Kong had to deal with overcautious decision makers. Director Mok Kwan-ling, whose movie was selected for a film festival screening, was requested [12] to make 14 cuts in her 25-minute film. She eventually refused, deeming the intervention as too far-reaching. The documentary “Revolution of Our Times,” about the 2019 social unrest, which was selected for the 2021 Cannes Film Festival and also won the Best Documentary Award at Taiwan’s 2021 Golden Horse Awards, has never been officially released in Hong Kong. Police have also remained intentionally ambiguous about the documentary’s internet release. Commissioner Raymond Siu Chak-yee stopped short of claiming that streaming the documentary would be a criminal act, but advised anyone to distance themselves. However, even uncontroversial movies have come under attack from pro-establishment media. In February 2022, columnist Chris Wat Wing-yin accused [13] the popular courtroom movie “A Sparring Partner” of having a covert political stance by portraying detectives in a less favourable way.

But other cultural content also started to disappear. In November 2021, the streaming platform Disney+ removed the Simpsons episode “Goo Goo Gai Pan,” during which the cartoon family visits China. The episode included several references to the crackdown on protests at Tiananmen Square in 1989 [14], and it remains unavailable on Disney+ in Hong Kong to this day. In early January 2022, it was revealed that public broadcasters in Hong Kong have blacklisted [15] several singers and music groups in Hong Kong, including Denise Ho, Anthony Wong Yiu-ming, Serrini, Charmaine Fong, C AllStar, and RubberBand. Artists such as Denise Ho have even struggled [16] to secure performance venues, as many are either directly managed by government agencies or are dependent on public subsidies.

In April 2022, the prestigious M+ museum, largely seen as the crown jewel of Hong Kong’s new arts district, seemingly removed [17] three controversial works of Chinese contemporary artists. While the official statement referred to a routine rotation of artworks, M+ had previously removed [18] Ai Weiwei’s “Study of Perspective: Tian'anmen” from its online catalogue. The famous image, which features a middle finger pointed towards the Gate of Heavenly Peace in Beijing, has remained greyed out [19], while other works of that series that feature the White House [20] in Washington DC or the Mona Lisa [21] painting in the Louvre remain accessible.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong Public Libraries have removed [22] several publications from their shelves, including books by political figures such as Joshua Wong. In July 2022, some publishers were also barred [23] from the annual book fair at the Exhibition and Convention Centre in Wan Chai. They were even unable [24] to secure another venue to host an alternative book fair.

While the sudden cancellation of the Batman screening was probably less of a concern for Hong Kong’s creative industry, the most recent incident of cinema censorship was rather alarming. Despite receiving initial clearance from the OFNAA, the newly released, low-budget horror movie “Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey” was suddenly pulled [25] from all local cinemas just days before its official release. The film distributor VII Pillars later shared that they were not given a specific reason for the sudden yet coordinated change of mind of local cinemas. Ever since the increasing popularity of internet memes that suggest a likeness between Winnie the Pooh and China's President Xi Jinping, the cartoon figure has been a common and recurring target for Chinese censors.

Please visit the project page for more pieces from the Unfreedom Monitor [26].