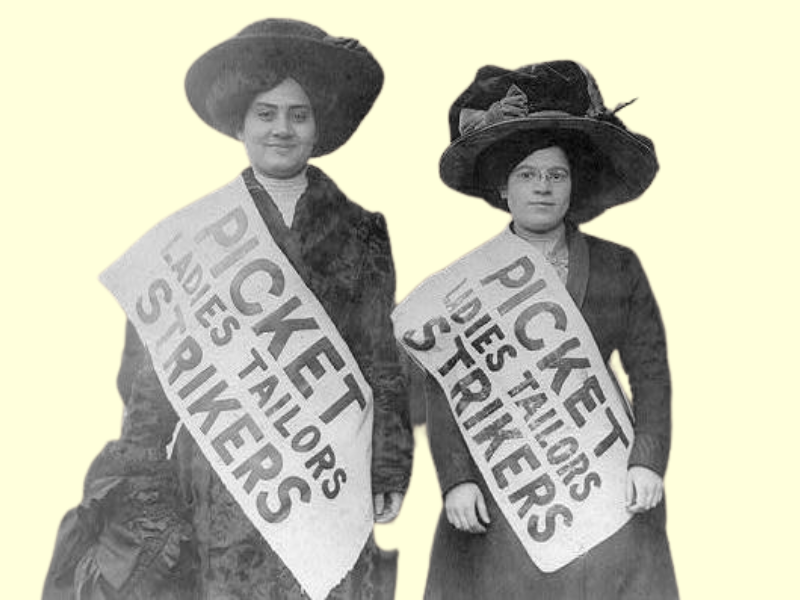

Global Voices illustration of an image of two striking women on the picket line during the New York Shirtwaist Workers’ Strike, “Uprising of the 20,000″. Public domain photo.

Today, few people realize that modern-day feminist struggles ultimately stem from the labor struggle of poverty-stricken women, working in garment factories, for instance. However, women's involvement in Argentina's trade unions is limited — something that gender historian Alexia Massholder would like to change.

Only 18 percent of women in unions currently hold leadership positions on Argentina’s trade union movement, with most working in the gender equality, culture, and social services fields. Only one woman to date has co-led the country's largest trade union, the General Confederation of Labor (CGT).

The origin of International Women’s Day, on March 8, comes from a combination of two separate movements. In 1909, female-led trade unions organized the first female worker's mass strike, which lasted eleven weeks. Two years later, a tragic blaze broke out in a New York garment factory. Most of its victims were young immigrant women, thus compounding their labor demands. In 1917, during the First World War, women workers in Russia also led a movement against the then-Russian Tsar, Nicolas II, under the slogan “Peace and Bread.”

Patricia Larrús: You talk about a turning point currently taking place in the feminist movement, what makes this moment so special?

Foto de Alexia Massholder, usada con su permiso.

Alexia Massholder: Si bien el feminismo no es algo nuevo, y viene abriéndose paso desde la osadía de pioneras como Olympe de Gouges, Mary Wollstonecraft y Flora Tristán, con importantísimos aportes teóricos y prácticos de mujeres como Clara Zetkin, Aleksandra Kolontái o Inessa Armand, las dimensiones como movimiento político son mucho más recientes. Las bases de una transformación profunda respecto al rol de la mujer en todos los ámbitos de la sociedad se están sentando en este momento sin dudas.

El crecimiento cuantitativo y cualitativo del feminismo como respuesta a la opresión de la mujer plantea una complejización respecto a las miradas sobre diferentes temas. Por un lado, nuevas preguntas y desafíos sobre la manera de hacer política, y también mayores articulaciones en las luchas contra la opresión de clase, raza, colonial, etc.

Por el otro, indudablemente, más allá de los desafíos nuevos y las complejidades internas, ya no hay manera de ocultar la cuestión de género en casi ningún ámbito, aunque nosotras mismas tengamos formas de pensar y actuar que no terminan de romper con «ideas» sobre la mujer, o formas de organización o de familia, que vienen siendo hegemónicas desde hace tantos años. Pero estamos en eso. Seguramente futuras generaciones lo resolverán más fácilmente. Tenemos esa responsabilidad por todas las que ya no están.

Alexia Massholder: Although feminism is nothing new and has been making headway ever since the courageous efforts of trailblazers like Olympe de Gouges, Mary Wollstonecraft and Flora Tristán, as well as the significant theoretical and practical contributions from women like Clara Zetkin, Aleksandra Kolontái or Inessa Armand, its growth as a political movement is much more recent. The groundwork for a profound transformation in women's role within all aspects of society is being laid right now, without a doubt.

The quantitative and qualitative growth of feminism as a response to women's oppression has led to a complex approach to different issues. On the one hand, there are new issues and challenges in how politics should work, as well as greater articulation in campaigns against class, race, and colonial oppression, etc.

On the other hand, there's really no getting around gender issues anywhere, even though we may have our own ways of thinking and acting that don't quite break with long-standing “notions” about women or organization and family types. But we’re working on it. Future generations will most probably be able to deal with this much better. We carry this responsibility for all those who are no longer here.

PL: What is your view on gender/class articulation?

AM: El feminismo como movimiento político se planta contra las relaciones desiguales y jerárquicas, y el sometimiento de identidades sexogenéricas [ed: identidades «sexuales» por la condición biológica y «de género» según el género con el que cada persona se identifica]. La profunda imbricación entre capitalismo y patriarcado ha configurado una división sexual del trabajo, roles específicos para la mujer y formas de opresión históricamente construidas.

Por supuesto que el feminismo avanza y se consolida por la ampliación de derechos, a partir de nuevas subjetividades. Pero al analizar la relación entre el patriarcado y el capitalismo se observa que la mujer es sometida por estos dos sistemas tanto en los espacios laborales remunerados (si es que las mujeres los alcanzamos) como en el espacio doméstico en donde las tareas de cuidado y reproducción de la mano de obra, son tareas no remuneradas. Se ocultan tras los discursos del amor maternal, el sostenimiento amoroso del marido, etc. Y la realidad es que esas tareas no remuneradas nos colocan a las mujeres en una posición completamente diferente a la de los hombres frente a nuestros trabajos. Y por eso es importante repensar nuestros espacios laborales y nuestra participación sindical también.

AM: As a political movement, feminism stands against unequal hierarchical relations and the subjugation of sexual and gender identities [ed: “sexual” identities based on biological status and “gender” based on the gender with which each individual identifies]. The considerable overlap between capitalism and patriarchy established the sexual division of labor, specific roles for women, and the historically constructed forms of oppression.

Based on new subjective viewpoints, feminism is of course making headway and strengthening its position with enhanced rights. However, upon analyzing the relationship between patriarchy and capitalism, the subjugation of women was found under both systems in paid work environments (if we get there as women) and domestic work environments, where reproductive labor and care duties go unpaid. These are hidden behind talk of motherly love and loving support of their husbands, etc. When it comes to our work, the reality is that these unpaid tasks put women in a completely different position to men. It’s thereby essential that we rethink our work environments and trade union involvement.

PL: Women taking an interest in unions is nothing new and actually dates back to the origin of the feminist struggle itself. However, this has long been a male-dominated environment. Women’s presence has declined and is currently experiencing new challenges. As a CONICET State Worker Association representative, what is your take on this endeavor today?

Photo of a women's right march, March 8, 2023, Buenos Aires, by Maria Paz Ismael PH. Used with her permission.

AM: Si bien la mujer siempre tuvo un rol fundamental en el mundo del trabajo, su representación política y sindical es más reciente. Si repasamos la historia del sindicalismo se verá que, como en todos los espacios que representan un poco de poder, la mujer ha estado prácticamente ausente. Y eso ha delineado un sindicalismo con reivindicaciones que no contemplan las particularidades del trabajo femenino en su mayoría. La ausencia de mujeres en paneles, programas curriculares, cargos, etc., se nota a simple vista.

AM: Although women have always had an essential role in the world of work, their political and trade union representation is much more recent. If we were to look back over the history of trade unionism, we would see that women have been all but absent. Much like in all places with a bit of power. Trade unionism is ultimately defined by demands that, for the most part, does not take into account female labor's specificities. The absence of women on panels, curricular programs, and in positions, etc. is plain to see.

PL: Lastly, what issues remain unresolved in Argentina’s labor field? What remains to be done?

AM: Es con el impulso y el empuje del movimiento feminista como movimiento revolucionario, transformador, en articulación con organizaciones sociales, políticas y sindicales, que se podrá lograr que las reivindicaciones por las que luchamos dejen de ser consignas y se transformen en leyes, regulaciones y convenios colectivos de trabajo, como lograr que se reconozcan las tareas de cuidado como un trabajo efectivo, erradicar la desigualdad imperante en el mundo del trabajo, ocupar los lugares que nos corresponden en la conducción y la decisión política tanto en nuestros trabajos como en los espacios sindicales.

No sólo como mujeres, sino también como lesbianas, trans y todas las identidades en la mayoría de los casos aún más perjudicadas en materia de derechos, dado la mirada hegemónica absolutamente binaria y heterosexual que impera en la política, el sindicalismo, la ciencia y los espacios de poder todos.

Si hoy podemos decir «El sindicalismo es con nosotras» ha sido por la fortaleza que el feminismo ha construido. Nuestra participación en el sindicalismo hoy es clave para poner una limitación a la doble opresión que mencionábamos antes, ya que nos permiten avanzar en nuestros trabajos, mejorar nuestras condiciones, nuestros derechos, como mujeres, lesbianas, no binaries, trans, madres, compañeras, como todo lo que decidamos ser.

AM: It’s with the feminist movement’s drive and energy as a transformative revolutionary movement, and by working in cooperation with social, political and trade union organizations, that we will be able to ensure the demands for which we fought, stop being slogans and become laws, regulations, and collective labor agreements. This includes, ensuring that caregiver duties are recognized as real jobs, eradicating existing inequalities in the world of work, holding the political leadership and decision-making positions to which we’re entitled in our jobs and trade unions alike.

Given the outright binary and heterosexual hegemonic views that prevail in politics, trade unionism, science, and places of power, this is not only for us as women, but also as lesbians, trans, and other identities that are more likely to be victimized in terms of rights.

Today, it is essential for us to be involved in trade unions in order to limit the double oppression mentioned above. If we can say, “trade unionism is with us,” it's due to the strength that feminism has gained. This will enable us to progress in our careers, improve our conditions and rights as women, lesbians, non-binary individuals, trans, mothers, partners, and anything else we decide to be.