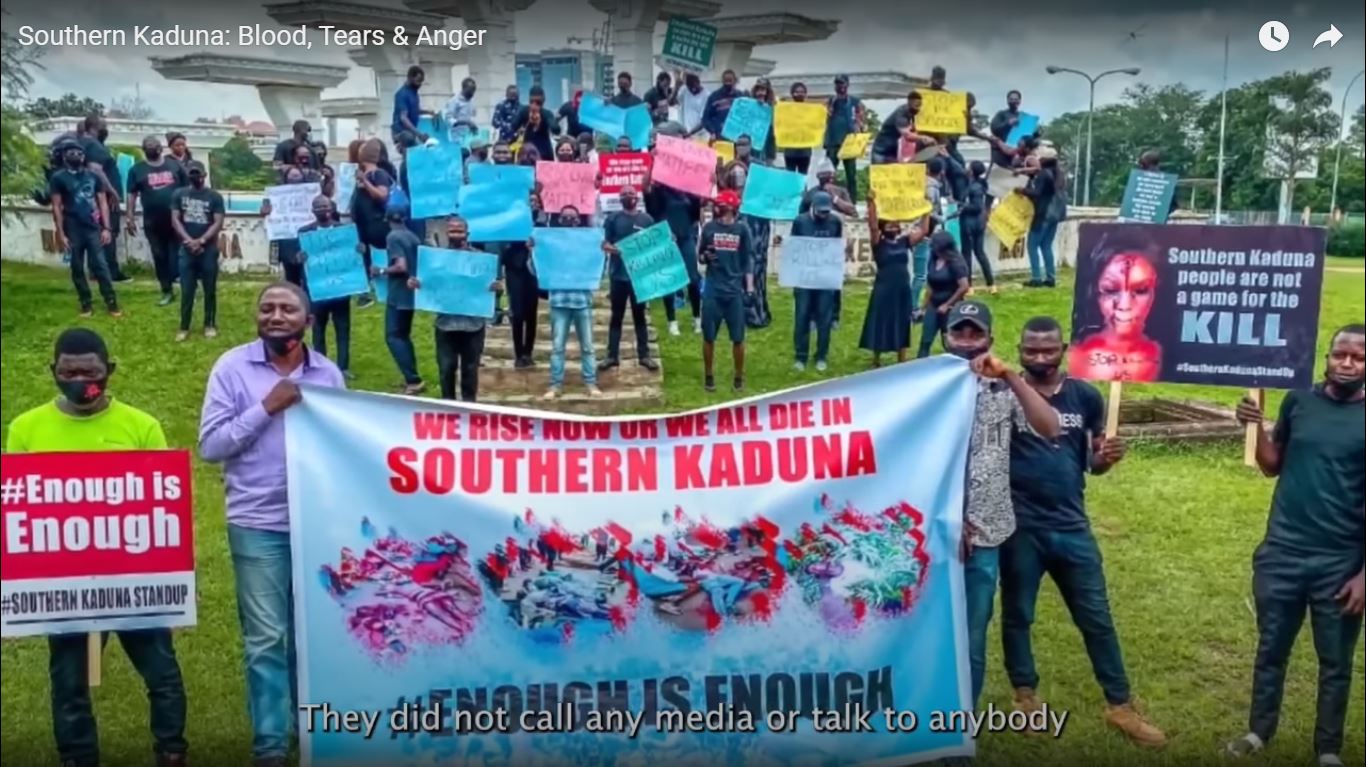

Screenshot of a scene from the documentary on YouTube. Used with permission.

For years now, Nigeria’s Southern Kaduna, a Middle Belt region made up of a diverse people with 57 ethnic groups including the Kataf, Ikulu, Muslim Hausa-Fulani migrants and others has been experiencing rising insecurity and multiple terror attacks in what appears to be religious and ethnic-based violence between Christians, Traditionalists, Indigenous ethnic populations, and Fulani Muslims.

The events have become a case of payback with reprisal attacks by the Christian Hausa/Fulani youth on Muslim Hausa-Fulani and vice versa, hence resulting in continuous bloodshed.

This comes as the country prepares to go into a general election in just a few days on February 25 and widespread violence across the country could threaten the safe conduct of the elections, according to Human Rights Watch.

As the election draws near, Nigerians are in high hopes of electing a new president who is expected to change the trajectory of the nation through improvement in the standard of living, peaceful coexistence without ethnoreligious violence in the country, an egalitarian society, and more.

History has it that the conflict in Southern Kaduna is the aftermath of the intrusion of the Fulani tribe into the north of the Niger area (present Nigeria) by the Arabic scholar Uthman Dan Fodio and his disciples. Moreover, the recent ethnoreligious crisis in Southern Kaduna is traced back to the 1980s. According to a 2017 Chatham House report, more than 20,000 people have died as a result of the conflict.

Meanwhile, on a TV programme ‘KadInvest 5.0’ in 2020, the governor of Kaduna state Mallam Nasir El-Rufai vowed to put an end to the perpetual killings, but regrettably, the homicides persist with a recent attack on the Southern Kaduna community members in December 2022.

Picture of the street reporter Beevan Magoni. Used with permission.

Upon realizing the lack of media coverage of the Southern Kaduna atrocities, Beevan Magoni, a Nigerian reporter based in Abuja and a native of Southern Kaduna, produced a documentary that delves into the ongoing horror story of Southern Kaduna from the point of view of the victims themselves.

The documentary, “Southern Kaduna: Blood, Tears & Anger,” traces the historical background of Muslim-Fulani attacks and the impacts of the communal crisis on the city whose population is approximately 4.5 million out of the country's total population of 213 million. Despite the ethnic diversity, the state — and Southern Kaduna in particular — has witnessed repeated ethnic violence. The heart-wrenching documentary, available on YouTube, contains graphic images and videos that bear witness to the atrocities and gruesome acts happening in the region.

Global Voices Yorùbá Lingua Manager, Adéṣínà (Ọmọ Yoòbá) caught up with Beevan Magoni in a WhatsApp interview to speak to him about the documentary.

Global Voices (GV): Why did you and other members of the production team decide to produce this documentary? What are the objectives and what motivated you to do it?

Beevan Magoni (BM): We were helpless in Southern Kaduna. It was a harvest of mass burials where the ground is dug every day and we pour our loved ones into it. It was frustrating that our people knew who these people were, and where they were but could not fight back because of the superiority of their firepower. We also suspect the government of Kaduna state under El Rufai knew about it, had a hand in it, or was covering up for some specific reasons.

I personally called and mobilized for protests which kind of slowed the killings but they resumed in full force, so a brother of mine (The popular Kaduna rapper known as D.I.A) called and said, let's do a documentary. Let's start keeping records of the wrongs done to us. Let's show our children why history is not being taught in school. Because things have been happening in that area right before the Jihad but they are not documented. Watch that part where the old man was narrating about the slave trade and all, that's history repeating itself, and let's do this to remind those to come to always be prepared and not be slaughtered like it is being done today.

GV: I stumbled on a website that claims that Christian Hausas have been attacking their Muslim neighbours for decades and the not-too-recent Kataf (Atyap) and Ikulu Christian youth staged reprisal attacks on Muslim Hausa-Fulani people in 2020. What can you say to this assertion?

BM: Christian Hausa is different from those of us in the Middle Belt. But for a fact, the most persecuted Nigerians are the Hausa/Fulanis who are Christians. They live under extreme persecution but they don't have a loud voice like we in the Middle Belt do.

What would you do if someone from your family kidnaps your daughter, forces her into marriage, and converts her? What would you do if you can't come out and say, “I am capable and I want to be voted for?” They don't have such power. They are crippled politically, economically, socially, and otherwise.

To the Middle Belt tribesmen, if they had carried out more reprisals like they were being attacked, that region would either be a war zone or a very peaceful place because no one is crazy to walk into a death trap.

I've heard of quite a number of the attackers being unfortunate not to return. Perhaps that's the narrative we are talking about here. There is a lot of fighting that's underreported.

GV: How long did it take you to produce the documentary and what were the challenges you faced?

BM: It took us two and a half years to finish everything. It was supposed to be a three week production or so, so I took two weeks’ leave to go work on it. Unfortunately, on the day we finished shooting, the drive fell and I lost everything. It felt like I was being sabotaged because everywhere I took it, no one could salvage anything. The last place was Edar lab in Abuja here and he said, bro, it can’t be repaired.

I had to start afresh, but this time, no extra resources, team members were tired, and I had to let them be in the interim. When I had gotten everything I was looking for, I then informed them, even though my team members Steven and Kefas were always on standby with me. You know, they call the three of us bandits because of how we were bent on getting the story told.

Financial support was zero. You suppose know say that one go dey (you should also know this). This is because our region doesn't understand media and how to invest in it so they didn't understand how far we could go. But, thank the gods, we are here!

GV: Were you not afraid of the consequences; of facing the wrath of the powers that be for exposing the ills perpetrated by these killers in your community as a false narrative?

BM: I have one life to live and I no dey fear (I am not afraid of) anybody! I am not a criminal. I don't go looking for trouble, but since childhood, everyone knows that you can't carry out injustice successfully in my presence. This lifestyle has gotten me into trouble multiple times but once I believe in a cause, there's no going back. The story had to be told.

GV: How did you get funds for the production of the documentary? What are the opportunities available for funding the project, the sponsors, and supporters?

BM: Funding was zero. From my salary and from a few friends. Sometimes I wait till the end of the month before going to Southern Kaduna, lodge in a hotel with my camera guys, wait to hear where people were being killed, and then move in. That's how we got those live footage of mourners.

GV: What will change? Will the documentary change anything, what do you think it can change? What do you hope it will achieve?

BM: A lot will change with time. There's so much to do at the moment, just waiting for the right people to come our way and we either work with them or point them in the direction to go. But most importantly, I want to see the children back in school. I want to see our homes that were destroyed rebuilt. I want to see those villages that number over 150 as we speak reoccupied by the original inhabitants. I want to see our human dignity restored.

While many like Beevan have pointed accusing fingers at the incumbent governor of Kaduna state, Mallam Nasir Ahmad El-Rufai, the governor has come out to say that he is not the sponsor of the crisis in his state. It may seem as though the root cause of the perpetual crisis in Southern Kaduna is either religious or ethnic. However, some schools of thought are of the view that the crisis is neither religious nor ethnic. The Street Reporter’s documentary is another angle on the events with a motive to shine a new beam of light on the killings and crimes against humanity perpetrated by some Hausa-Fulani groups in Southern Kaduna from a novel perspective.

1 comment

Thank you GV