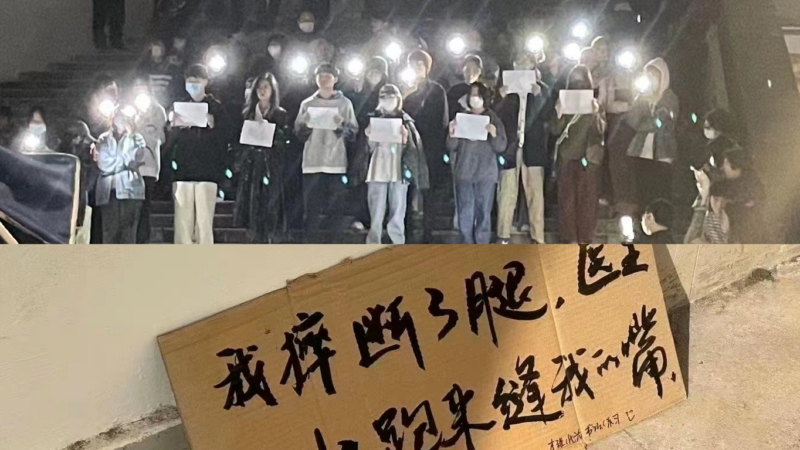

Viral photos showing the protests at the Communication University in Nanjing. The protest slogan: “I broke my leg, the doctor came and sealed my mouth.”

An unknown number of anti-zero COVID policy protesters faced forced disappearance during Christmas and Lunar New Year break in China. The disappearances — arrests and detentions — are drawing criticism and condemnation from various human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

China took a U-turn on the country’s zero-COVID policy after a round of nationwide protests triggered by a great fire in Urumqi, Xinjiang, in November. While Chinese President Xi Jinping said in his new year address that “it is normal” for people to hold different views, the public security authorities have detained and arrested at least a few dozen protesters since December.

It is difficult to estimate the scale of the crackdown as relatives of the arrestees refused to speak out for fear of more serious allegations. Thus far, most of the known arrestees are from Beijing and they have friends from overseas who learned about their disappearance.

According to an investigative report from HRW, the Chinese public security authorities have detained dozens of students, journalists, and other civilians who participated in the protests. Some of them have been released on bail and others are in detention. Several of them, including four Chinese journalists, were formally arrested and charged with crimes including “picking quarrels and creating troubles” and “gathering a crowd to disrupt public order.”

The wave of peaceful protests, dubbed the White Paper Protests or White Paper Revolution, took place in major cities across China, including Shanghai, Beijing, Chengdu, Guangzhou, and Wuhan, with thousands of protesters holding blank papers calling for an end to the draconian zero-COVID policy. Most protesters chanted, “We Want Freedom, No to PCR or lockdown,” and a few chanted, “Down with the Communist Party.”

After the protests, conspiracy theories spread on social media that foreign forces fuelled the protests. As Beijing switched tactics and ended the zero-COVID policy, the public security authorities secretly launched a nationwide crackdown on the protests.

The arrestees

The crackdown began in early December and only caught public attention in mid-January 2023, after one of the arrestees, Cao Zhixin (曹芷馨), a Remin University graduate and editor, released a pre-recorded video urging the world not to let the white paper protesters disappear in silence:

In the video, Cao explained that she and her five friends were detained for 24 hours by Beijing police on November 30, for commemorating the Urumqi Fire in Beijing Liangma River on November 27. Then beginning December 18, her friends disappeared one by one. Foreseeing her arrest, she recorded the video and asked her friend to help release it when she became unreachable. Cao was taken by Beijing police on December 24.

The majority of known arrestees, including Zhai Dengrui (翟登蕊) and Cao Zhixin, are either feminists or are connected to the Chinese feminist social circle:

In this profile of a group of women friends in Beijing who have been rounded up by authorities and become accidental symbols of dissent in China, we unpacked a fundamental shift in China's civil society. Please read: 1/ https://t.co/6nSPMoF8pZ

— Shen Lu @shenlu@alive.bar (@shenlulushen) January 25, 2023

The public security authorities targeted not only street protesters but information disseminators such as reporters and online protest supporters and wider communication networks such as chat groups.

International press freedom watchdog, RSF condemned the arrest of four journalists, including Li Siqi (李思琪), Wang Xue (王雪), Yang Liu (楊柳), and Qin Ziyi (秦梓奕) in Beijing during the protest crackdown. The charges that they faced ranged from “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” and “gathering a crowd to disrupt public order.” The latter can carry a penalty of life imprisonment.

According to other online sources, members of online chat groups were also arrested. Yang Zhanqing, a human rights activist, detailed two of the arrest cases on Twitter:

据悉,北京亮马桥白纸抗议青年 #李元婧 被批准逮捕是因为她是群主,而 #李思琪 被逮捕的原因是她往群里(该群的聊天内容都被警方掌握)拉了很多外媒记者。其实,李思琪是自由撰稿人,刚从英国留学回来,她平常交际圈有很多外媒的人,拉朋友们进来聊天,算是正常事情,但到了国安那里就成了罪证之一。

— 杨占青 (@yangzhanqing) January 23, 2023

Sources said Li Yuanjing was arrested for being the administrator of a chat group. Li Siqi was arrested because she invited many foreign journalists into the group. As a freelance journalist, Li had just returned home from her study in the UK She had many foreign journalist contacts and it was normal for her to chat with them. However, the security police took that as a piece of evidence to incriminate her.

Those who helped out the protesters were also at risk. According to HRW, lawyers who tried to provide legal assistance to arrestees were threatened. Even those who assisted the bailout of friends would get themselves into trouble, according to Yan Zhangqing:

#李超然(网名Cathy),95年出生,北师大本科、人大硕士,毕业后就职于北京一金融机构。她是音乐剧资深爱好者,热爱观鸟和星空摄影,生活中除了爱好就是无尽加班。她并未参与2022年11月27日晚北京”亮马桥”举白纸行动,只是担保了白纸运动一个青年释放,在2023年1月6日失联至今,可能也被检察院批捕。 pic.twitter.com/RjPalxSQIV

— 杨占青 (@yangzhanqing) January 20, 2023

Li Chaoran (screen name Cathy), born in 1995, graduated from Beijing Normal University and finished her MA at Renmin University. She started working in a financial institution in Beijing upon graduation. She loves music and taking pictures of birds and starry nights. She always works overtime. She did not attend the Maliang River protest on November 27. She just helped bail one protester out. Then on January 6, she disappeared. Probably the judiciary has approved her formal arrest.

Those who disseminated protest information were also harassed:

Kamile Wayit, a 19-year-old college student at a university in Hebei province, was detained by police in December after returning to Xinjiang on winter break after posting video about the recent ‘white paper’ protests across China. https://t.co/9fnbG0NIj6#A4Movement #白纸抗议

— Shao Jiang 邵江 (@shaojiang) January 26, 2023

Implications of the white paper protests

Among overseas Chinese, there have been some discussions on the implications of the protests and their crackdown. It is clear that the nationwide protests sped up the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) COVID policy reversal:

“White paper movement” did make policy impact according to insiders

In late Nov, “protests erupted across China.. The rare display of public anger, w/ some protesters directly criticizing Xi & CCP, alarmed Xi & his inner circle..officials & advisers said” https://t.co/ywpNVVohUO

— Vicky Xu / 许秀中 (@veryvickyxu) January 4, 2023

Yet, many, including exiled Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, believed that the unorganized protests had a very limited impact on the single-party regime. Another Chinese activist, He Peirong, anticipated the likely impact:

白紙革命的影響,是让中共意識到經濟發展,是他們政權的唯一合法性來源。持續的封控導致經濟蕭條,動搖執政基礎。他們放開,並且鼓勵感染,是指望徹底擺脫新冠影響,來年春天的經濟復甦。這個冬天死去的人,就是那個代價。這個冬天裡經歷的,你就是那個代價,無論你支持哪個政策。

— Ho Peirong (@pearlher) December 23, 2022

The impact of the White Paper Revolution is to let CCP acknowledge the fact that their sole legitimacy comes from economic development. The prolonged lockdowns bought economic downturn and challenged the foundation of its legitimacy. Hence, they opened up and encouraged infection in order to get rid of COVID before spring came. The price is the lives that passed away this winter. What we have gone through this winter is the price, regardless of whether you support or oppose the [zero-COVID] policy.

Despite the political crackdown and the lack of public support within the heavily censored Chinese social media, some remain optimistic about future political changes. @lausanhk interviewed a newly formed collective of young overseas Chinese activists who saw the anti-zero COVID protests as the beginning of a new political awakening movement:

The White Paper Revolution is producing a new generation of politicized youth—many of whom, like Cao Zhixin, have already begun to face arrest. Read our interview with China Deviants, a collective of Chinese diaspora activists, on their organizing work:https://t.co/SvXiHN0mSu

— Lausan 流傘 (@lausanhk) January 20, 2023