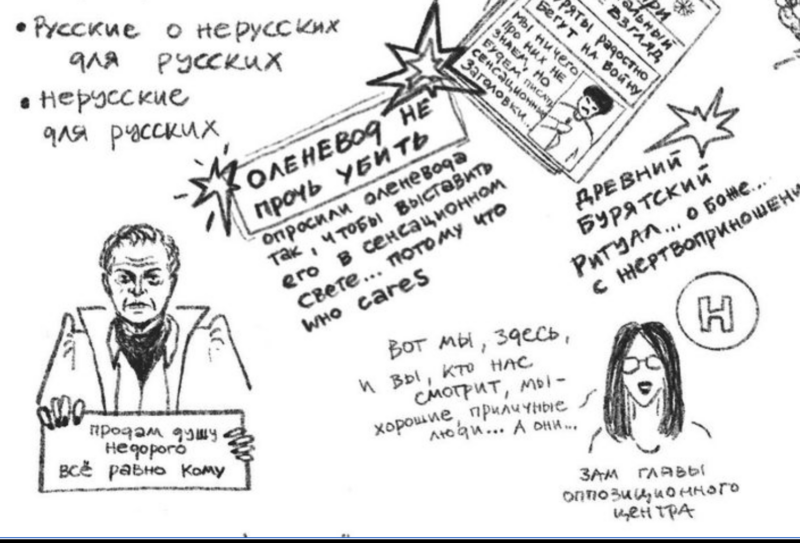

Detail of illustration by Seseg Jigjitova, a Buryat artist deconstructing Russian colonialism. Used with permission.

According to statistics, Russia is home to over 190 ethnic groups [1] in which ethnic Russians account for around 80 percent [1] of the total 146 million population [2]. Yet Moscow maintains a Russian-centric discourse [3] largely inherited from a Soviet colonial tradition. But its invasion of Ukraine [4] has triggered new anti-colonial and anti-war initiatives among some of its non-Russian nations. Global Voices spoke in Russian over email to Buryat instagrammer Seseg Jigjitova who uses visual art to bring awareness about the need to decolonize Moscow's narratives.

Jigjitova comes from Buryatia, a region in Southern Siberia around Lake Baikal that is home to one of the Mongolic nations of Russia, the Buryats [5]. Trained as an architect, and now based in Berlin, she recently started using her work as an illustrator to draw and write in Russian about the issue of decolonization, based on the example of what she describes as several ‘Asian ethnic groups’ (Buryat, Tuvan [6], Sakha [7] and other people living in Siberia and the Far East) experience as minority groups perceived through the lenses of ethnic Russians.

Her work on Instagram [8] combines images and text to illustrate the discourse of colonization, its manifestations and consequences. The art is accompanied by her commentaries, as well as reactions to her short texts, revealing a rich discussion on an issue that remains sensitive and largely ignored in mainstream public discourse in Russia. Indeed the opposition to Putin often mirrors the same Russian-centric view, as seen with Aleksey Navalny [9]. Global Voices asked Jigjitova why this remains a blind spot:

Я вижу в этом страх потери привилегий и определенного статуса. По-человечески мне этот страх очень даже понятен. Ведь если мы начнём копать глубже, то мы увидим, что деколонизация затрагивает все сферы жизни: начиная от школьного образования, топонимов, языков, медиа, культуры и заканчивая самым главным – мышлением, а также идеей превосходства колонизаторов над колонизируемыми. Действительно, сложно не испытывать тревогу, понимая, что этот глубинный процесс неизбежен, и, более того, он уже начался, а ты – хочешь не хочешь – его активная часть.

Для русских оппозиционеров и их последователей быть против Путина – уже довольно радикально и смело. Я здесь абсолютно не хочу нисколько умалять их вклада в антивоенную и анти-пропагандистскую борьбу. Однако, судя по всему, многие просто не хотят зреть в корень проблемы и, как следствие, признать Россию колониальной страной.

Справедливости ради, необходимо признать, что и коренным народам РФ предстоит очень большая работа по деколонизации себя. И в первую очередь, осознать свой так называемый статус субалтерна – почти бесправного члена общества, которого большинство не слышит, не видит и просто не желает воспринимать. Это – отправная точка, с которой надо начать двигаться. Объективно, без прикрас осознать своё положение и что и как к этому привело.

К счастью, наша слабость может обернуться и нашей силой: когда угнетённые народы, разделяющие одну на всех боль, солидаризируются, происходит синергетический эффект. В этом наше преимущество, неочевидное для большинства. К тому же, мы не только солидаризируемся друг с другом – азиатскими республиками России – но и получаем моральную поддержку других народов: казахов, монголов, восточных европейцев.

Любопытно, что Свободная Бурятия – единственная этническая организация, которой российские оппозиционные медиа регулярно дают эфир. Предположу, что это связано с тем, что глава фонда, А. Гармажапова, неоднократно публично заявляла о приверженности идеи сохранения федерации. А тот же В. Милов, например, в одном из своих интервью говорил, как он рад, что «мы вместе» (имея в виду Бурятию). Параллельно с этим, многие оппозиционные эксперты и медиа-лидеры говорят о возможности распада РФ исключительно как катастрофе.

Уверена, людям нужно давать шанс решать собственную судьбу самостоятельно. При этом, конечно, необходимо раскрыть все архивы и сделать их доступными, признать колониальное прошлое и настоящее и максимально объективно и прозрачно обсудить все “за” и “против”. В конце концов, деколонизация вовсе не обязательно означает отделение. Но если отделение – это осознанный выбор общества вследствие деколонизации… то почему нет?

What I see in this is a fear of losing privileges and a certain status. As a human being, I understand this fear. If we dig deeper, we will see that decolonization touches all areas of life: schools, place names, languages, media, culture, and, importantly, ways of thinking, as well as the notion of colonizers being superior to the colonized. Really, it’s hard not to feel anxious when you realize that this far-reaching process is inevitable. Moreover, it has already begun, and you are its active participant, whether you want it or not.

For Russian opposition leaders and their followers, to be against Putin—even that is very radical and bold. In no way do I want to diminish their contribution to the anti-war and anti-propaganda efforts. However, it seems that many people are simply unwilling to get to the root of the problem and, as a result, acknowledge that Russia is a colonial country.

In all fairness, it needs to be recognized that the Indigenous peoples of the Russian Federation have a lot of work to do to decolonize themselves. First, they need to recognize their status as the subaltern, a nearly powerless member of society where the majority does not hear, see, or want to accept it. This is the starting point for us to begin moving from. To see our situation as it is, without embellishment, and to recognize what led to it and how.

Fortunately, our weakness can also become our strength: when the oppressed peoples who share the same pain as one come together, it creates a synergy. This is an advantage we have that is not obvious to most. There’s more to this, too. Not only do we find solidarity with each other, Russia’s Asian republics, but we also find moral support among other peoples: the Kazakhs, the Mongols, the Eastern Europeans.

What’s interesting is that Free Buryatia, [10] [exile group of Buryat opponents to Putin's policies] is the only ethnic organization to get regular airtime in the Russian opposition media. My guess is that this is because Aleksandra Garmazhapova [11], who leads the organization, has repeatedly and publicly voiced her commitment to preserving the federation. Meanwhile, in one of his interviews, Vladimir Milov [12][an opponent to Putin], for example, said how glad he was that “we are together” (referring to Buryatia). At the same time, when talking about the possible collapse of the Russian Federation, many opposition experts and media leaders speak about it solely in terms of a catastrophe.

I am convinced that people need to be given the chance to choose their own destiny. In doing so, it is of course necessary to open up all archives and make them [publicly] accessible, recognize the colonial past and present, and have a conversation about all pros and cons in a way that is as objective and transparent as possible. After all, decolonization does not have to mean secession. But if, as a consequence of decolonization, society consciously chooses secession… then why not?

In this image, a man in military forms grabs a person and the text above reads “We need more meat” in reference to young Buryat men being disproportionately sent to the Ukrainian front as ‘cannon fodder” (which n Russian it is literally called ‘cannon meat)

The demonizing of those ethnic groups comes from different sources: Russian nationalists, but also the Vatican [14] or certain Ukrainian nationalists [15]. Global Voices asked Jigjitova the origins of this on-going othering of non-white or non-Christian ethnic groups.

Да, мне кажется, это всё та же древняя шарманка о «тёмных, жестоких дикарях» и «белых людях, несущих свет и гуманность».

Вот, Патриарх Кирилл недавно выступил с заявлением, что, мол, «православная совесть» не позволяла русским колонистам жестоко обращаться с местным населением во времена колонизации Саха. Здесь тоже, вновь и вновь, сказки про добровольное вхождение сибирских народов и регионов в состав Российской империи. А ведь люди продолжают в них верить.

Москва в царское и в советское время превратила Сибирь в каторгу – естественную тюрьму. Место, которое для одних было родной землёй и домом, а для других – удобной возможностью расправиться с неугодными, послав их подальше от себя.

Yes, I think that it’s the same old song about the “ignorant, cruel savages” and “white people who bring light and humanity”.

Recently, Patriarch Kirill [16] [Head of the Russian Orthodox Church] made a statement that during the colonization of Sakha it was their “Orthodox conscience” that did not allow the Russian colonists to mistreat the local population. Here too, again and again, we hear the story of how the Siberian peoples and regions were voluntarily incorporated into the Russian Empire. And yet people continue to believe these stories.

During Tsarist and Soviet times, Moscow turned Siberia into its forced labor camp, a natural prison. This is a place that for some people was their land and home, and for others a convenient way of dealing with the undesirable by sending them as far away as they could.

In her art, Jigjitova deconstructs Russian colonialism using Russian as the language of communication. Global Voices asked her what she hopes to achieve and what kind of reaction she gets:

В своём инстраграм-аккаунте я делюсь собственными наблюдениями и опытом, расту вместе со всеми. Я получаю много положительных отзывов от представителей коренных народов, некоторые из них пишут мне в личные сообщения с обратной связью, время от времени разворачиваются очень интересные дискуссии. Иногда я использую свои сторис, чтобы публиковать мнения людей, желающих высказаться анонимно, – я очень ценю это доверие. Мне важно говорить о своей антивоенной позиции и, если необходимо, давать площадку для таких же антивоенных голосов коренных народов. Ростки нашей деколонизации пока что очень слабые и маленькие, но они растут и крепнут. И я очень хочу поддержать «своих» в процессе обретения субъектности.

Осознание колониального прошлого России, колонизации Сибири и её последствий очень важно для настоящего и будущего. Без разбора полётов не будет процветания – ни для потомков колонистов, ни для колонизированных. Нужно перестать ставить памятники колонизаторам в сибирских городах и праздновать «добровольное присоединение». Вместо этого нужно сделать всё возможное, чтобы сохранить языки, вернуть истинные, коренные названия рекам, озёрам, местностям, деполитизировать учебники истории и прекратить эту безумную гегемонию всего русского. У бурятов, например, есть своя литература – не менее великая. Эвенкийские народные сказки абсолютно достойны того, чтобы их изучали во всех школах. А тувинцы, несмотря ни на что, сохранили свой язык – 85% говорят на родном языке, и это огромный ресурс и потенциал аутентичности.

Это самое очевидное, первое, что приходит в голову. Конечно, процесс деколонизации и излечения коллективных травм займёт многие десятилетия, обретёт новые формы и переизобретёт старые. Так что мне, на самом деле, сложно ответить, каковы признаки «настоящей» деколонизации. Я могу только делиться своей перспективой.

In my Instagram account, I share my own observations and experiences and I grow along with everyone else. I get a lot of positive feedback from Indigenous people: some of them send me personal messages with their feedback and occasionally I see very engaging discussions unfold. Sometimes I use my [Instagram] stories to share the views of individuals who want to speak while remaining anonymous, and I really value their trust. It's important for me to talk about my own anti-war position and, if needed, to provide a platform for similarly anti-war Indigenous voices. The beginnings of our decolonization are still very fragile and small, but they are growing and getting stronger. And I really want to support “my own” in the process of growing their agency.

Recognizing Russia's colonial past, the colonization of Siberia and its consequences is very important for the present and the future. Without looking back and learning the lessons, there will be no prosperity for the descendants of the colonists or for the colonized. We must stop building monuments to the colonizers in Siberian cities and celebrating its “voluntary annexation” [to Russia]. Instead, we should do everything possible to preserve languages, bring back their true, Indigenous names to rivers, lakes, and localities, depoliticize history textbooks, and stop this insane hegemony of all things Russian. The Buryats, for example, have their own literature, and it is no less great. Evenki [17] folk tales absolutely deserve being studied in all schools. And the Tuvans have, in spite of everything, preserved their language: 85 percent of them speak their native language, and this is a huge resource and an opportunity for authenticity.

These are some of the most obvious things that first come to mind. The process of decolonization and the healing of collective trauma will certainly take many decades; it will take new forms and reinvent old ones. This is why it’s actually hard for me to say what the signs of “real” decolonization are. I can only share my perspective.

In this image, two intellectuals debate about Indigenous peoples. The one on the left, responding to the question “What do you think of the wish of those who want to separate from us?” says: “Yes, without us [referring to ethnic Russians] they will return to their villages.” The one on the right adds: “Impossible. We need to reform the redistribution of resources…They [Indigenous people] will not be able manage those resources, they are not read yet..when I say they are ready, then…”

Russian language uses two words when referring to Russian identity: the first is “русский” [russki] which means ethnic Russian, and “россиянин” [rossiyanin] which means citizen of the Russian Federation. Global Voices asked Jigjitova about her own relation to the term Russian as an identity marker:

Мне не хочется говорить о русской идентичности. Я не знаю, как русские идентифицируют себя. Про себя точно могу сказать: я – нерусская, я – бурятка. Спасибо моим родителям, которые воспитывали во мне «нормальность» бурятской идентичности. В то же время, во мне очень много русского, всё же мы все выросли на русской классической литературе. Это, безусловно, дало мне многое, но эта же всеобщая зацикленность на всём русском ещё больше у меня отняла – по сути, целые другие миры и опыты.

Так получилось, что мы, нерусские, знаем всё про русских, но они ничего не знают о нас. Более того, мы сами в этом коллективном беспамятстве мало что знаем о нас самих. Я очень рада, что всё больше коренных людей задаются вопросом: что значит быть бурятом, тувинцем, саха и т.д.? Это сейчас один из самых главных вопросов для нас.

I don't want to talk about ethnic Russian identity. I don't know how ethnic Russians identify themselves. What I can say with certainty about myself is that I am not an ethnic Russian; I am a Buryat. I’m grateful to my parents who encouraged me to think of my Buryat identity as something normal. At the same time, I have a lot of Russian in me; after all, we all grew up on Russian classical literature. This has certainly given me a lot, but this universal fixation on all things Russian has taken even more away from me, essentially whole other worlds and experiences.

It so happens that we, non-Russians, know everything about [ethnic] Russians, but they know nothing about us. Moreover, in this collective oblivion, we know little about ourselves. I’m so happy that an increasing number of Indigenous people are asking the question: What does it mean to be Buryat, Tuvan, Sakha, and so on? This is one of the most important questions for us right now.

Jigjitova's quotes were translated from Russian into English by Marina Khonina [19].