Elvi Sidheri, photo by the author, used with permission.

Elvi Sidheri had spent four days between the plastic seats in Madrid's Barajas Airport, waiting for the immigration agents to be so kind as to give him an answer. He had traveled to perfect his language skills thanks to a scholarship from Casa España in Tirana, Albania. He had already lost count of how many times he had recited in his mind the verses of the poets Lope de Vega, Góngora, and García Lorca. He had already been improving his Spanish, not in the classroom, but in convincing the police that he was not carrying drugs and had no plans to settle in Madrid; he just wanted to get to know the city. He could have felt like a Quixote in the year 2000, but, if so, no one would have questioned his entry into the Kingdom of Spain, which now seemed so different from the wonders he imagined. His only sin was to have an Albanian passport, a country from which only catastrophic news came.

The wait was too long and he decided to turn back. His patience had reached its limits. “If Spain doesn't want to receive Elvi, Elvi doesn't want to enter Spain either,” he said to himself, reinforcing a trait that characterizes him to this day: talking about himself in the third person. He turned around, asked for his passport, and boarded the next flight to Albania. He got to know and did not get to know Madrid on that occasion

Political contexts have hindered the dissemination of Albanian culture in the world. The international isolation of Albania during the communist regime of Enver Hoxha (1944-1985) and the current diplomatic blockade of Kosovo, a country recognized today by 97 of the 193 members of the UN, have contributed to portraying a culture that, even in the context of the Balkans, is seen as most enigmatic. There are an estimated five to six million people who ethnically identify themselves as Albanians. They form the largest ethnic group in Kosovo (around 93 percent) and the largest ethnic minority in Northern Macedonia. Albanians also have a considerable presence in Montenegro, Italy, and Greece, as well as a significant ethnic diaspora in the United States, Italy, and Northern Europe.

More than twenty years after his first attempt to visit Spain, Elvi Sidheri is one of the few translators and cultural mediators between the Ibero-American and Albanian worlds. In fact, he is an extensive connoisseur of the Romance cultural world and, in particular, of Spain since he is a translator of Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese into Albanian, and has dedicated two novels to “Spain: Two Worlds” (Dÿ bote, in original Albanian) published in 2019, and “To Spain with Love” (A España con Amor) published in 2021.

We spoke to Elvi Sidheri via email. This has been edited for length.

Elvi Sidheri, photo by the author, used with permission.

Global Voices: What was your image of Spain after experiencing such an unpleasant situation at the airport of Madrid?

Fue muy impactante, ya que me di cuenta de que la España de mis sueños de juventud, la que había conocido leyendo a Lope de Vega, Góngora y García Lorca, era otra cosa. Pero, aunque fui consciente que la realidad era distinta, no sentí ningún resentimiento hacia España. Volví a los pocos años, en 2004, y después muchas otras veces, cada vez que podía. De hecho, después de dos décadas tomé esa experiencia como inspiración y la plasmé como autor en una parte de mi libro publicado en 2021, A España con amor, por más que el libro no sea autobiográfico.

Elvi Sidheri (ES): It was very shocking, as I realized that the Spain of my youthful dreams, the one I had known by reading Lope de Vega, Góngora and García Lorca, was something else. But, although I was aware that the reality was different, I did not feel any resentment towards Spain. I went back a few years later, in 2004, and then many other times, whenever I could. In fact, after two decades, I took that experience as an inspiration that I captured it as an author in a part of my book published in 2021, “A España con amor” (To Spain with love), even though the book is not autobiographical.

GV: How did you reconnect with the Hispanic world afterward?

Fui a América casi inmediatamente después de esta primera fea experiencia y fue muy oportuno porque en el Caribe pude reencontrar las raíces de mi amor por el mundo hispano, su cultura y su lengua. Fui a República Dominicana y al principio me sentí casi como en casa porque estaba lleno de turistas italianos, que son muy parecidos a nosotros, los albaneses. En mi país la cultura y la lengua italianas están muy presentes. Y después empecé a apreciar la forma relajada en que vivían los lugareños, el clima, la naturaleza, el mar azul y la música. Después en Cuba me sentí muy atraído por su orgullo, la cultura asombrosa que tienen y la arquitectura colonial de Santiago de Cuba y La Habana. Descubrí que, aunque España y América Latina tienen orígenes comunes, como la misma lengua y algunas tradiciones, el Caribe e Hispanoamérica son realidades lejanas, que difieren visiblemente de España y de Europa.

ES: I went to Latin America almost immediately after this first ugly experience and it was very timely because in the Caribbean I was able to rediscover the roots of my love for the Hispanic world, its culture, and its language. I went to the Dominican Republic and at first I felt almost at home because it was full of Italian tourists, who are very similar to us Albanians. In my country, the Italian culture and language are very present. And then I started to appreciate the relaxed way the locals lived, the climate, the nature, the blue sea and the music. Then, in Cuba, I was very attracted by their pride, the amazing culture they have, and the colonial architecture of Santiago de Cuba and Havana. I discovered that, although Spain and Latin America have common origins, such as the same language and some traditions, the Caribbean and Latin America are distant realities, which differ visibly from Spain and Europe.

GV: What could you tell us about these cultural differences between Spain and Latin America from your perspective and experiences?

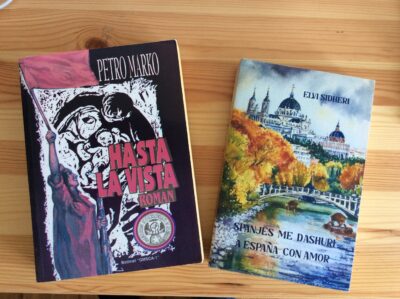

“Hasta la Vista,” by Petro Marko and “A España con Amor,” by Elvi Sidheri. Photo by the author, used with permission.

España es casi un típico país de Europa Occidental: desarrollado, moderno, de mentalidad abierta, aunque mantiene sus raíces mediterráneas. América Latina ha heredado la mayor parte del legado cultural español, como su lengua y muchas tradiciones, pero también ese maravilloso Nuevo Mundo ha creado su propia conciencia, a partir de la mezcla de muchas culturas y etnias que emigraron a lo largo de los siglos y se fusionaron con el componente nativo y con personas de otros orígenes como África y Asia.

ES: Spain is almost a typical Western European country: developed, modern, open-minded, while maintaining its Mediterranean roots. Latin America has inherited most of the Spanish cultural legacy, such as its language and many traditions, but also that wonderful New World has created its own consciousness, from the mixture of many cultures and ethnicities that migrated over the centuries and merged with the native component and with people from other origins such as Africa and Asia.

GV: In this mixture of cultures in Latin America, how do you see, from Albania, the native component you mention and its interaction with other cultures? Do you see similarities between this reality and your Balkan context?

Las poblaciones indígenas conforman la parte más importante de la imagen que tenemos de América Latina, y en particular la que yo tengo como hispanófilo porque son el corazón mismo del continente americano. Pienso en la mezcla de etnias, lenguas, tradiciones y raíces que aportaron civilizaciones históricas y también en el aporte de culturas nativas: sin ellas América Latina no sería la misma.

La península balcánica también ha estado habitada por muchas naciones diferentes y la región siempre ha sido una encrucijada de civilizaciones, religiones e imperios. Soy muy consciente de que mi identidad albanesa fue forjada por la mezcla de estos pueblos y culturas a lo largo de los siglos.

ES: The Indigenous populations make up the most important part of the image we have of Latin America, and in particular the one I have as a Hispanophile because they are the very heart of the American continent. I am thinking of the mixture of ethnicities, languages, traditions, and roots that contributed historical civilizations and also in the contribution of native cultures: without them Latin America would not be the same.

The Balkan peninsula has also been inhabited by many different nations and the region has always been a crossroads of civilizations, religions, and empires. I am well aware that my Albanian identity was forged by the mixing of these peoples and cultures over the centuries.

GV: Do you find cultural similarities between the Balkans and Latin America?

Seguramente podemos encontrar muchas, sí. Aunque no me gusta hablar de aspectos negativos hay que mencionar que en estas dos regiones hay problemáticas comunes como falta de estabilidad, problemas económicos, crisis gubernamentales, dictaduras pasadas y sistemas democráticos híbridos. Afortunadamente también compartimos una actitud en la vida cotidiana de vivir con alegría, somos irascibles, despreciamos las dificultades que enfrentamos y hay un cierto disfrute de la lentitud en el día a día que nos permite apreciar los pequeños placeres que se nos presentan. Me gusta pensar que, en cierto modo, los Balcanes son la América Latina de Europa en muchos aspectos hermosos.

ES: Surely we can find many, yes. Although I do not like to talk about negative aspects, it should be mentioned that in these two regions there are common problems such as lack of stability, economic problems, governmental crises, past dictatorships, and hybrid democratic systems. Fortunately, we also share an everyday attitude of living with joy, we are quick-tempered, we despise the difficulties we face, and there is a certain enjoyment of the slowness of everyday life that allows us to appreciate the small pleasures that come our way. I like to think that, in a way, the Balkans are the Latin America of Europe in many beautiful ways.

GV: Are there Albanian words that have clear translations into Spanish, but at the same time, translating them into other languages is difficult because there are no equivalents?

Creo que sí. Pienso en la muy típica palabra española “siesta” que puede traducirse fácilmente con la palabra albanesa “kotem”: una especie de siesta relajante, que también implica una tradición del lento disfrute de la vida que ambas culturas compartimos.

ES: I think so. I think of the very typical Spanish word “siesta” that can be easily translated with the Albanian word “kotem:” a kind of relaxing nap, which also implies a tradition of the slow enjoyment of life that both cultures share.

GV: And if you had to choose just one Spanish word, what would it be?

La que siempre me ha fascinado es “hermosa”, ya que es una de las primeras palabras que aprendí al leer el libro “La judía de Toledo” de Lion Feuchtwanger. Es un escritor judío alemán sobreviviente del Holocausto que en su novela describe el amor entre el rey Alfonso VIII y Raquel, una muchacha judía a quien llamaban la “Fermosa”. Para mí, España y el mundo y culturas hispánicas son simplemente hermosas.

ES: The one that has always fascinated me is ” hermosa” (gorgeous), since it is one of the first words I learned when I read the book “The Jewess of Toledo” by Lion Feuchtwanger. He is a German Jewish writer and Holocaust survivor who describes in his novel the love between King Alfonso VIII and Raquel, a Jewish girl who was called the “Fermosa.” For me, Spain and the Hispanic world and cultures are simply gorgeous.

GV: Which Spanish and Latin American authors do you like or enjoy translating the most?

Me encanta hacer traducciones especialmente de poetas, ya sea de España o de América Latina, y debo señalar que mi primera traducción del español fue de tres de las Novelas Ejemplares de Miguel de Cervantes. Todo el tiempo traduzco autores, como Octavio Paz, Mario Benedetti, César Vallejo –uno de los poetas más difíciles de traducir–, Jaime Sabines, Pablo Neruda y, mi favorita en absoluto, Elvira Sastre.

ES: I love translating, especially from poets, whether from Spain or Latin America, and I should point out that my first translation from Spanish was three of Miguel de Cervantes’ Exemplary Novels. I translate authors all the time, such as Octavio Paz, Mario Benedetti, César Vallejo —one of the most difficult poets to translate —, Jaime Sabines, Pablo Neruda, and, my absolute favorite, Elvira Sastre.

GV: What literature is there on the relationship between the Albanian and Hispanic worlds?

Poca y no está traducida. El clásico de referencia es el famoso libro Hasta la vista (NdR: título original en albanés) del gran autor Pietro Marko, donde describe la Guerra Civil Española inspirado en sus propias experiencias como voluntario de las Brigadas Internacionales. Nunca se ha traducido al español y yo siempre recomiendo su traducción por su disidencia a la dictadura y las experiencias que cuenta. También me gustaría destacar mi libro A España con Amor, en el que describo las relaciones culturales y humanas entre albaneses y españoles desde la década de 1930 hasta nuestros días a través de tres historias de amor en tres épocas diferentes. (NdR: en junio se ha publicado en España la novela policial La espía de cristal de Pere Cervantes, que ambienta una historia de amor entre un reportero español y una sobreviviente de guerra albanesa en el Kosovo de la posguerra)

ES: Few and most is not translated. The reference is the famous book “Hasta la vista” (Ed.: original title in Albanian) by the great author Pietro Marko, where he describes the Spanish Civil War inspired by his own experiences as a volunteer in the International Brigades. It has never been translated into Spanish and I always recommend its translation for its dissidence to the dictatorship and the experiences he tells. I would also like to highlight my book “To Spain with Love,” (A España con Amor), which describes the cultural and human relations between Albanians and Spaniards from the 1930s to the present day through three love stories in three different periods.

GV: Since Albanian literature is little known, who should we pay attention to in order to better understand this cultural landscape? The name of the writer Ismail Kadaré always comes up, but who else is there?

La literatura albanesa está viviendo una especie de renacimiento, después de la caída del régimen totalitario en Albania, pero también en Kosovo, y hay muchos escritores talentosos que están creando una nueva ola sin vínculos, pocas influencias y una mentalidad distinta al antiguo régimen y sus reflejos en nuestro espacio literario, como pueden ser Erjus Mezini o Kristaq Turtulli.

Kadaré es un grande, y eso no lo digo yo, sino los lectores de medio mundo en los más de treinta idiomas en la cuales han sido traducidos sus libros. Pero sus obras están inevitablemente vinculadas a aquel periodo histórico. Él supo jugar majestuosamente con la censura, señalando problemas que nadie más podría. Sin embargo, un hecho lamentable en el que caen muchos cuando escriben sobre Albania es tomar siempre como punto de referencia la violencia del Kanun medieval, las Vírgenes Juradas, la dictadura de Hoxha, la prostitución, las organizaciones criminales mafiosas y nada más, como si Albania y los albaneses fuéramos sólo eso. Es algo muy despectivo, que no le hace justicia a Albania ni a su literatura.

ES: Albanian literature is living a kind of renaissance after the fall of the totalitarian regime in Albania, but also in Kosovo, and many talented writers are creating a new wave with no ties, few influences, and a different mentality from the old regime and its effects on our literary space, such as Erjus Mezini or Kristaq Turtulli.

Kadaré is one of the greats, and I am not the one saying it, but rather the readers around the world who read in the more than thirty languages into which his books have been translated. But his works are inevitably linked to that historical period. He knew how to play majestically with censorship, pointing out problems that no one else could. However, a regrettable fact that many fall into when writing about Albania is to always take as a point of reference the violence of the medieval Kanun, the Sworn Virgins, the Hoxha dictatorship, prostitution, mafia criminal organizations and nothing else, as if Albania and Albanians were only that. It is a very derogatory thing, which does not do justice to Albania and its literature.

GV: Indeed, when talking about “Albania” and “Kosovo,” negative stereotypes tend to proliferate, or at least premodern and dark ones. How can cultural production counteract these representations and offer the world a more accurate, modern, and cosmopolitan vision of today's Albania and Kosovo?

Tanto extranjeros como muchos autores albaneses suelen enfocarse en esto, quizás, porque les resulta más fácil que profundizar en otras cosas. En mi literatura, por el contrario, siempre trato de centrar la atención en el carácter cosmopolita ancestral típico de los albaneses. Por ejemplo, en el hecho de que nuestra tierra desde siempre ha sido encrucijada de civilizaciones, lenguas, culturas y tradiciones y eso lleva a una mentalidad abierta y a una hospitalidad característica que se aprecia, entre otras cosas, en el rescate de los judíos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial o en la acogida de refugiados de la guerra de Kosovo en 1999. Intento destacar de nuestra Besa –código de honor tradicional albanés– nuestra actitud alegre y nuestra obstinación y carácter invencible ante las dificultades de la vida, el mal destino, los invasores y los regímenes opresores.

ES: Both foreigners and many Albanian authors tend to focus on these things, perhaps, because it is easier for them than to delve into other aspects. In my literature, on the contrary, I always try to focus on the ancestral cosmopolitan character typical of Albanians. For example, on the fact that our land has always been a crossroads of civilizations, languages, cultures and traditions and that leads to an open-mindedness and a characteristic hospitality that is seen, among other things, in the rescue of Jews in World War II or in the reception of refugees from the Kosovo war in 1999. I try to bring out from our Besa — the traditional Albanian code of honor — our cheerful attitude and our stubbornness and invincible character in the face of life's difficulties, bad luck, invaders and oppressive regimes.

GV: What future collaboration can we expect between the Albanian world and the Hispanic world considering that they are peripheral spheres of global cultural production?

Estoy seguro de que seguirán construyéndose puentes culturales entre nuestras culturas y gente, especialmente a través de la literatura, y daré lo mejor de mí para dar mi aporte en este contexto, como autor y como traductor.

ES: I am sure that cultural bridges will continue to be built between our cultures and people, especially through literature, and I will do my best to contribute in this context, both as an author and as a translator.