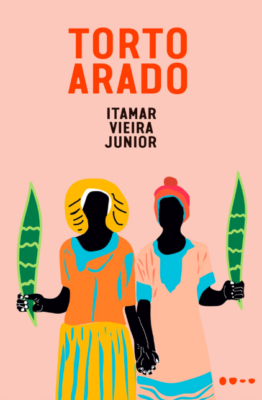

Itamar Vieira Junior, author of the literary phenomenon ‘Torto Arado’ | Image: Adenor Gondim/Editora Todavia

A few days before the first round of Brazil’s presidential elections, with far-right incumbent Jair Bolsonaro facing leftist former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, in the end of September, Brazilian writer Itamar Vieira Júnior [1] stood on stage in front of a large audience and endorsed Lula’s candidacy.

He explained how public libraries turned him into a reader, and what he learned from his parents, amidst an impoverished childhood. “I had the privilege of writing a story that has found many readers. A story that takes place in Bahia's countryside; it still shows the wound of slavery in our days, that there are still workers being exploited in the fields and in the cities.”

“Torto Arado” [2] (Crooked Plow [3], in English) is the story of two sisters from northeastern Brazil's Bahia state, and their lives with the echo of an accident from their childhood. The book ends with a message that “over the land, shall always live the strongest one.”

“The strongest is the people, is Brazil, and that’s why we will vote for Lula and we're for democracy,” said Vieira at the event [4] of the now president-elect [5].

Born on the outskirts of Salvador, Bahia, Vieira, 43, is a literary phenomenon in his country. “Torto Arado” has sold over 400,000 copies [6], was translated into other languages [7], has its cover illustration tattooed by fans, and will become a series on HBOMax [8].

The book was first published in Portugal in 2019, after winning a prestigious literary award [9], and only came to Brazilian readers a few months later when it became a hit.

Even as a successful author now, Vieira, who is also a geographer, has kept his job as a public servant at Incra [10], the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform in Brazil, responsible [11] for land policy and the agrarian reform.

The organization was one of those weakened under Bolsonaro’s government [12], like the National Indigenous Foundation (Funai [13]) and the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable National Resources (Ibama [14]).

Vieira told Global Voices in a video chat that the decision to publicly defend his vote for Lula was also inspired by another Brazilian writer, Raduan Nassar [15].

After years of avoiding interviews and retired from writing, Nassar began to make public appearances in 2016 to speak up against the impeachment of former president Dilma Rousseff [16]. He also showed up side-by-side with Lula before the latter's imprisonment — the convictions were later annulled [17].

In this interview with GV, Vieira talks about his work and Brazil in and out of the 2022 elections:

Itamar Vieira Júnior at a pro-Lula event in September, days before the first round of elections | Screenshot/PT Facebook [4]

Global Voices: You mentioned how your book found many readers, which you didn’t expect. “Torto Arado” is a best-seller, and became a literary phenomenon; to what do you credit all that?

Itamar Vieira Júnior (IVJ): Para quem escreve sempre é difícil falar sobre isso, mas eu fico com as impressões que os leitores compartilham comigo. Embora o Brasil seja um país diverso, com muitas origens, é uma história que ainda assim comunica um pouco da nossa história coletiva, que de alguma maneira não foi contada como deveria, tanto pela historiografia oficial, quanto pelas artes mesmo. Esse movimento é mais recente, com honrosas exceções do passado. Talvez seja uma vontade que os brasileiros têm de conhecer o próprio país.

Itamar Vieira Júnior (IVJ): It’s hard for writers to talk about it, but I keep the impressions that readers share with me. Even though Brazil is a diverse country, with many origins, it’s a story that still communicates a lot of our collective history, which wasn’t told as it should have been, somehow, neither by the official historiography and nor by the arts. This is a recent movement, with honorable exceptions in the past. Maybe it’s a willingness that Brazilians have to get to know their own country.

GV: How was the process of thinking about this story and your time living in it?

IVJ: A primeira inspiração eram as histórias familiares que se contavam. Meu pai, meus avós tiveram origem no campo, em comunidades do Recôncavo na Bahia, e essas histórias sempre fizeram parte da minha vida. Mas, também, foi muito estimulada pela literatura brasileira da primeira metade do século 20, os autores do ciclo do Nordeste, por exemplo, escreveram com muita propriedade sobre os conflitos fundiários – Graciliano Ramos, Rachel de Queiroz, Jorge Amado, José Lins do Rêgo, João Cabral de Mello Neto. Foi assim que nasceu o mote inicial, a história das duas irmãs, numa propriedade rural e a relação que elas tinham com o pai.

Mas ao longo do tempo ela foi mudando. Eu fui trabalhar como servidor público, há mais de 16 anos, no Maranhão e depois na Bahia, diretamente com trabalhadores rurais, com indígenas e quilombolas, com comunidades tradicionais ribeirinhas e aprendi muita coisa sobre esse mundo. Acho que a história ganhou mais densidade, profundidade e pude contá-la da melhor maneira possível.

IVJ: My first inspiration were stories told by my family. My father and my grandparents have their origin in the countryside, in the Reconcavo region [18] in Bahia state, and these stories were always part of my life. But it was also stimulated by the Brazilian literature from the first half of the 20th century, authors from the Northeastern cycle, who wrote about land conflicts so well — Graciliano Ramos, Rachel de Queiroz, Jorge Amado, José Lins do Rêgo, João Cabral de Mello Neto. That is how the plot was created, the story about two sisters, in a rural property, and their relationship with their father.

But it changed through the years. I went on to work as a public servant, over 16 years ago, in Maranhão and then Bahia, with rural workers, with Indigenous people and quilombolas [19], with traditional riverside communities and I’ve learned a lot from this world. I think the story gained density, depth and I was able to tell it the best possible way.

Torto Arado original Brazilian cover | Image: Todavia publishing

GV: How was it living with this story?

IVJ: Acho que quase 25 anos, porque eu era adolescente quando a história surgiu. Inclusive o título é desse momento. Eu comecei a escrever e escrevi 80 páginas, que depois se perderam em alguma mudança, mas essa história continuava a me habitar. Fui estudar, fui para a universidade, fui trabalhar e aí a vida vira um tumulto, eu não tinha tempo para dar atenção a essa história. Como a literatura com o passar dos anos foi fazendo mais parte da minha vida, cada vez mais, essa vocação gritou mais alto à medida que fui me tornando mais velho. Foi assim que essa história foi amadurecendo.

Quando eu terminei [meu percurso acadêmico], eu decidi me dedicar com mais afinco à literatura, eu já tinha dois livros de contos publicados, e aí eu escrevi esse romance, então, os originais foram parar em Portugal, concorrendo ao Prêmio LeYa. O livro surgiu por isso, depois despertou o interesse da editora Todavia no Brasil. O livro foi publicado em 2019, em Portugal, meses depois aqui e aos poucos foi encontrando leitores, foi acontecendo.

IVJ: I think it lasted 25 years, because I was a teenager when the story came along. Actually, the title is from back in those days. I started to write and wrote 80 pages, which I ended up losing in moving, but the story continued to live on in me. I went on to study, entered university, went on to work and then life turns in turmoil and I didn’t have time to pay attention to it. Since literature was becoming more and more part of my life as the years went by, every time, this call rang louder as I was getting older. This is how the story was maturing.

When I finished [my academy path], I decided to dedicate myself more seriously to literature. I'd already written two short story books, and so I wrote this one and sent the original to the LeYa award in Portugal. The book appeared because of this award, and then aroused the interest of Todavia publishing in Brazil. It was published in 2019 in Portugal first, and months later here, where it started to find readers little by little.

GV: The book's last line says something like, “over the land, shall always live the strongest one.” What does it mean in a country with the continental dimension Brazil has, where land conflicts are still killing people?

IVJ: Eu trabalho com camponeses há mais de 16 anos, o forte e o fraco são categorias que existem com muita frequência nesse meio. A planta está forte, o chão está fraco. Eu penso na nossa história colonial, nessa história de violência que o Brasil viveu ao longo dos séculos, de imaginar sempre quem é o forte. Muitas vezes, na voz dessas pessoas, o forte é quem tem poder econômico, quem tem a fazenda, quem é o proprietário. É curioso e, ao mesmo tempo, paradoxal. Se a gente for olhar a nossa história, de violência contra os povos indígenas, contra a população da diáspora negra, é uma história de muitas atrocidades, e como essas pessoas sobreviveram?

A história de Torto Arado, no fundo, é uma história de força, de coragem, é mostrar que os sobreviventes é que são os mais fortes. Aquelas personagens são sobreviventes de uma história que nem começa com elas, uma história ancestral, de muita violência. Mas elas sobreviveram e não deixaram a terra a despeito de tudo. Foi pensando nisso que essa frase é o desfecho dessa história.

IVJ: I have worked with farm workers for over 16 years now, weak and strong are categories that exist often in this environment. The plant is strong, the soil is weak. I think about our colonial history, this history of violence that Brazil endured for centuries, imagining who is the strongest one. Many times, in these people’s voices, the strong one is the one with the economic power, who owns the farm, who is proprietary. It’s curious and paradoxical at the same time. If we look into our history, of violence against Indigenous people, the people from the Black diaspora, it’s a history of so many atrocities, and how did these people survive?

“Torto Arado”’s story, deep down, is about strength, courage and showing that the ones who survive are the strongest. Those characters are survivors of a story that starts before them, an ancestral story, with so much violence. But they survived and did not leave the land despite everything. Thinking about all of this I made this sentence the foreclosure of the story.

GV: You did two DNA tests to discover your origins. What made you do it and what did it change for you?

IVJ: Eu sou um homem mestiço. A família de meu pai tem uma ascendência negra e indígena, a de minha mãe, branca e negra. A família da minha mãe tem ascendência ibérica, portugueses do norte de Portugal, região do Minho, pessoas que migraram para o Brasil fugindo da pobreza e chegaram nos anos 1910 em Salvador. Sobre essa parte da família, tínhamos muitas informações, conseguíamos fazer a árvore genealógica, e isso para mim era marcante, porque eu não tinha o mesmo sobre os outros ancestrais. Era como se soubesse apenas uma parte da minha história.

Esses testes foram se tornando mais baratos, e eu não pensei duas vezes, quando eu pude fazer. Se eu não posso afirmar com toda a certeza, eu sei pelo menos de que região da África vieram meus ancestrais negros, da Costa da Mina, entre Serra Leoa e Nigéria. A história indígena e negra brasileira sofreu um apagamento brutal, histórico.

Essa questão da identidade é complexa, porque eu sempre me enxerguei como um não-branco, mas falar não-branco é trazer a centralidade do branco na minha vida e não é bem assim. Claro, tenho ancestralidade branca, como boa parte dos brasileiros, mas se a gente pensar a história da colonização nas Américas é uma história de violência, violência sexual inclusive, contra mulheres indígenas e negras.

[O teste] resgatou um pouco da minha história que estava perdida, diluída na minha cor mais clara, e me devolveu uma identificação que também é política, muito importante neste momento que vivemos.

IVJ: I’m a mixed-race man. My father’s family has Black and Indigenous ancestry, and my mother’s, white and Black. My mother’s family has Portuguese ancestry, from the northern region of Portugal, Minho, people who immigrated to Brazil escaping poverty and arrived in Salvador in the 1910s. About this side of the family, we had a lot of information. We were able to trace the family tree, and it was remarkable to me, because I didn’t have the same from my other ancestors. It was like if I’d only known part of my history.

These tests became cheaper, and I didn’t think twice when I was able to afford it. If I cannot affirm with absolute certainty, I know at least from which region of Africa my ancestors came, Costa da Mina [20], between Sierra Leone and Nigeria. The Black and Indigenous history has suffered a brutal, historical erasure.

This identity issue is complex, I’ve always seen myself as non-white, but saying non-white is to bring the white to the center and it’s not that. Of course, I do have white ancestors, as a good portion of Brazilians do, but if you think about the colonial history in the Americas, it is a history of violence, sexual violence included, against Black and Indigenous women.

[The test] rescued a bit of my history that was lost, diluted in my lighter complexion, and gave me an identity that is also political, so important at this time we’re living in.

GV: You've worked as a public servant at Incra for years now. What did you learn and what can us you tell about it?

IVJ: Trabalhar no campo me deu uma medida de como esse país é diverso. Acho que, no campo brasileiro, as nossas mazelas estão de alguma maneira registradas, são parte da paisagem, então, fica muito mais fácil compreender o que é esse país. Trabalhei com várias coisas ao longo desse tempo, com alfabetização de jovens e adultos, acompanhando projetos, com assistência técnica de trabalhadores rurais, aplicando crédito, participei de campanhas de documentação da trabalhadora rural, com regularização de territórios quilombolas.

Tenho consciência da importância de tudo que é feito nesses lugares para a nossa segurança alimentar, para a preservação ambiental. Porque, se a gente for olhar, no Brasil, as grandes propriedades produzem commodities, que podem ser importantes para a balança comercial, mas a gente não come commodity. O Brasil é um país que produz mais de 270 milhões de toneladas de grãos por ano, é mais de uma tonelada por habitante, mas temos 33 milhões passando fome, porque as pessoas não comem soja pura. Isso me deu uma medida da importância do que é o campo para o nosso país, tanto para conhecer a nossa história, quanto para projetar um país e um futuro que seja possível para todos, aliando preservação ambiental e produção de alimentos.

IVJ: Working in the rural fields gave me an idea of how diverse this country is. I think that, in the Brazilian fields, our ills are somehow registered, they are part of the landscape, so it gets easier to understand this country. I’ve worked with many areas during the time [at Incra], with literacy project for youngsters and adults, following up projects, with technical assistance to rural workers, applying credit to them, I’ve participated in documentation campaigns to the women rural workers, with regularization of quilombola lands.

I’m conscious of the importance of everything that is done in these places for our food security, for environmental preservation. Because, if you take a look in Brazil the large properties produce commodities, which may be important to trade balance, but we do not eat commodity. Brazil is country that produces over 270 million tons of grains every year, which is more than a ton per person, but we still have 33 million people in hunger, because people do not eat pure soy. This gave me a measure of how important the land is for our country to know our history, and also to project a country and a future viable to all, allying both environmental preservation and food production.

GV: Agrarian reform is something always postponed in Brazil. For example, it was one of the causes defended by President João Goulart [21] when he suffered a military coup in 1964 [22]. Is it now possible to advance on it in Brazil?

IVJ: Eu acho, ainda acredito. Eu vejo a história de outros países, México, Egito, Moçambique, vários países fizeram a reforma agrária. E ela não é algo que você faz uma vez e o problema está resolvido. É uma política pública contínua, que deve ser feita ao longo do tempo. É uma cláusula pétrea da nossa Constituição, a função social da propriedade – é um bem econômico, mas ela precisa ter uma função social. A gente sabe dos problemas que tem o agronegócio, mas ele é muito diverso. Tem aqueles que são inimigos do país, de fato, que desmatam, mas tem os que são conscientes, porque isso é exigido pelos compradores das nossas commodities.

Acho que o Brasil não pode abrir mão do agronegócio, não é algo que está no nosso horizonte, mas pode aliar essas duas maneiras de desenvolvimento social. É possível o agronegócio e preservação ambiental, e é possível também o agronegócio nas pequenas e médias propriedades. Agora, é preciso ter um equilíbrio e é aí que o Estado é imprescindível

IVJ: I think so, I still believe in it. I see the history in other countries, Mexico, Egypt, Mozambique, several countries that underwent a land reform. And it is not something you do it once and the problem is solved. It’s a continuous public policy, that should be made through time. It’s an indelible clause in our Constitution, the social function of propriety [23] — it’s an economy good, but it needs to fulfil a social function. We know about the problems in the agribusiness sector, but it is also widely diverse. There are those who are enemies of the country, people who carry deforestation on, but there are also those people who are conscious, because commodities buyers demand so.

I think Brazil cannot give up on agribusiness, it’s not something in our horizon, but we can align these two forms of social development. It's possible to have agribusiness and environmental preservation, and it's possible to have agribusiness in small and medium lands. It's necessary to have a balance and that is where the State is indispensable.

GV: You’ve met rural leaders who were assassinated, and you were threatened yourself, right? Can you talk about it?

IVJ: Tem sempre risco. Eu mesmo já recebi ameaças veladas, pessoas dizendo para não aparecer mais ali, fazendeiros descobrindo meu telefone e ligar fazendo assédio ostensivo. Essa violência ocorre contra servidores, mas a gente tem a proteção do Estado, eu já fiz operações com acompanhamento da polícia. Mas uma pessoa comum, uma liderança de comunidade, quase nunca pode fazer isso. A gente passou por anos críticos, esses últimos anos foram de grande violência. Essa história de morte no campo nos acompanha desde sempre, mas ela não pode ser banalizada. Estamos no século 21, é inadmissível que aconteça ainda hoje, e que boa parte desses crimes não se chegue a uma solução, o que termina favorecendo que novos crimes aconteçam. Nesse governo, então, nem se fala.

Parece que eles se sentem autorizados a fazer isso – carros de servidores foram queimados na Amazônia, unidades do ICMBio queimadas por garimpeiros, madeireiros, parece que nós viramos criminosos por tentar cumprir a legislação, fazer aquilo que é correto. Nosso trabalho é pragmático, delimitado, tudo tem embasamento jurídico, normas, leis, decretos derivados da Constituição. Não é nada da nossa cabeça, vontade própria. É um momento muito crítico.

IVJ: There are always risks. I did receive veiled threats, people telling me not to show up in a place anymore, farmers getting my phone number and calling to harass me. This violence occurs against public servants, but we have State protection, I already did some operations with police support. But regular people, community leaders, almost never have that. We went through critical years, these last few years were of great violence. This history of deaths in the fields follows us for a long time, but it cannot be trivialized. We’re in the 21st century, it’s inadmissible that it’s still taking place and that a good portion of these crimes are never elucidated, which helps new ones to keep happening. In this government, don’t get me started.

It seems they feel authorized to do these things: public servants’ official cars were burnt in the Amazon, ICMBio (Institute to Preserve Biodiversity) [24] units burnt by illegal miners, loggers; it’s like we became the criminals for trying to comply with the law, doing the right thing. Our work is pragmatic, delimited, everything has a legal ground, norms, laws, decrees originated from the Constitution. It’s not pulled out of our heads, our own will. This is a very critical time.

GV: Has manifesting your support for Lula interfered in your work at Incra?

IVJ: Eu não estou fazendo uma manifestação institucional, estou me manifestando como cidadão, como qualquer outro cidadão. Algum dia pode aparecer algum questionamento, mas até o momento, não. O tempo pede, urge que todos nós tenhamos um posicionamento muito claro. Não é uma questão de um candidato ou outro que está disputando, não é uma eleição normal. São valores, lutas de uma vida que podem ser perdidas. A democracia está em risco e uma parte da população compreendeu isso.

Eu nasci no período da ditadura, eu vi meu pai e minha mãe votarem pela primeira vez para presidente em 1989. Meu pai tinha mais de 30 anos. E eu lembro de toda a emoção que eles estão vivendo, panfletando, isso é muito importante. É uma luta histórica que a gente não pode deixar que se perca. Muitos perderam a vida nessa luta, a gente tem que ter apreço. Pode ser uma democracia imperfeita, mas ela ainda é melhor do que qualquer outra coisa. Foi nela que conseguimos alguns avanços importantes na nossa história.

IVJ: I’m not doing an institutional expression I’m expressing myself as a citizen, just like anyone else. Someday there may appear some questions, but so far there haven't. The time asks, demands, that all of us have a very clear stand. It’s not about one candidate or the other, this is not a regular election. There are values, lifetime fights that can be lost. Democracy is at risk and a part of the population did understand it.

I was born during the dictatorship, I saw my parents being able to vote for a president for the first time in their lives in 1989. My dad was in his 30s. And I remember the emotion they were going through, delivering pamphlets; this is really important. It’s a historical fight that we cannot let be lost. So many people gave their lives in this, we need to appreciate that. This might be an imperfect democracy, but it’s still better than any other thing. It was in it that we made some important advances in our history.

GV: What is at stake with this year’s presidential elections?

IVJ: Eu acho que estamos diante de dois projetos: um projeto imperfeito, mas que ainda assim é civilizatório, e um projeto que só nos entrega violência e barbárie. Então, é importante, inclusive para a existência do Brasil e dos brasileiros, que a gente abrace nosso país nesse momento, para que a gente batalhe para não retroceder.

IVJ: I think we’re facing two projects: one imperfect, but still civilizing, and the other one that only delivers violence and barbarism. So, it’s important, even for the existence of Brazil and Brazilians, that we embrace our country now and battle to not go backwards.