Photos courtesy of the participants with illustration by Giovana Fleck and layout design by Natalie Van Hoozer.

When isolation measures were put in place around the world at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Latinas with disabilities were no strangers to handling confinement, loneliness, and figuring out how to care for themselves, day in and day out, in order to survive.

For them, the global health crisis increased barriers, as well as their caregiving responsibilities and dependence on others. These findings are supported by international studies. To illustrate these experiences first-hand, six women with disabilities from different countries, some immigrants, participated in facilitated conversations. The diversity of the interviewees is represented in the map below:

ALT TEXT: The preview image of the StoryMap digital tool features six photos of women wearing masks, as well as a map of the world marking six different locations in Latin America, Spain and the United States. A transcript of the text on the map and alternative text describing the photos can be accessed here.

The participants shared how, from the confines and comforts of their homes, they solved challenges brought about by COVID-19. They turned to their mutual support networks and used skills they had cultivated prior to the pandemic because of their disabilities. The three conversations, facilitated in pairs for this project, have been woven together to create the following fictitious conversation to illustrate their experiences.

The doorstep

The women explained that during the isolation period of COVID-19, whether they could leave the house was the luck of the draw.

CRISTINA: COVID created barriers for us that we had overcome before the pandemic. We try to be as autonomous as possible, but we’re obligated to ask for help from other people.

PAMELA: In the building where I live, a friend would bring packages sent to me by mail to my door.

ZARÍA: I brought my mom to my house to live with me, and we hunkered down, we shut ourselves in. It was very clear to me that there wasn’t any type of concerted effort to save people like us during the pandemic, and there wasn’t going to be.

The screen

Even though up-to-date information is a lifeline in times of pandemic, it is not always accessible or inclusive.

CRISTINA: The global health crisis has demonstrated that people with disabilities deserve to have resources and services adapted to their needs in emergency situations.

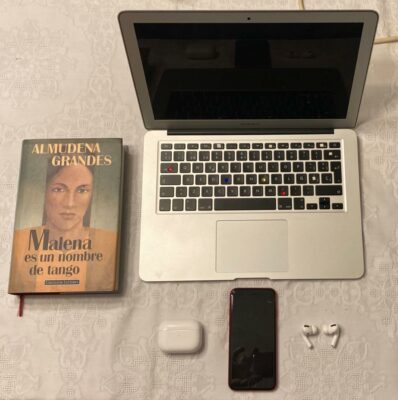

These objects represent the isolation period of the COVID-19 pandemic for Lida Margarita Carriazo, who is originally from Colombia and currently lives in Sama, Asturias, Spain. Photo courtesy of Carriazo.

KARINA: The information available about who was allowed to go out and who wasn’t, at what time, was always displayed on graphs and maps without any kind of description or alternative text.

CRISTINA: Those of us in the disability community effectively lobbied to have sign language interpretation provided at the Dominican government’s daily COVID press conferences. We also sent the government lists with the names of people who were confined to their homes and didn’t have essential resources and support.

ZARÍA: Many online activities are disappearing (due to many places opening up again). The hybrid format (virtual and in person activities) shouldn’t go away, because participating virtually is accessible for those of us who have mobility problems. Another issue is safety: it is not safe to go out because many places don’t have proper ventilation or adequate social distancing. The streets, which have so much commotion, are an especially high-risk place to be.

The desk

Private spaces, including these women’s homes, converted into places of work during the pandemic. While this prevented exposure to COVID-19, it did not stop discrimination toward the women who took part in these conversations.

PAMELA: I switched to working 100 percent virtually during the pandemic. While I do experience discrimination, I also have privileges that come with living in the United States, where laws are enforced. It’s important to be conscious of our privileges and the ways in which we are oppressed. In developing regions, [at the beginning of the pandemic] I would have had to take my chances going out into the world to work, because in other places, that’s the only option.

In Mexico, Zaría Abreu Flores chose her inhaler as an object that represents the pandemic for her. Photo courtesy of Abreu Flores.

ZARÍA: Since I lost my job, I’m no longer economically independent. There are also organizations that won’t hire me because I am an activist working to bring visibility to long COVID, which has progressively disabled me and makes it hard for me to plan things. Potential employers ask me, “What if you get sick and you can’t finish your work?” If they’d let me, I would do the work from home.

LIDA: On the contrary, they should be saying, “Because you’re dealing with long COVID, let’s see how we can help you.”

ZARÍA: Right, but it just doesn’t work that way due to ableism.*

The window

Being near the window, on the patio, or in a relaxing at-home space was a way for the women interviewed to care for themselves and figure out how to approach life during the pandemic, without having to leave the house.

ZARÍA: I’m a sick person who cares for myself and for others. I’ve taken on more self-care, on top of caring for my mom. My partner also provides me support, but I’m the only one who can take care of my mental health.

MARGARETH: When I got COVID, my children did too. My newborn little girl got sick, as well as my two older boys, who had a fever for two days.

Originally from Colombia, Lida Margarita Carriazo lives in Sama, Asturias, Spain, and her guide dog Raquel is now her companion to navigate the world. Photo courtesy of Carriazo with illustration by Giovana Fleck.

LIDA: Lockdown at the beginning of the pandemic wasn’t so bad for me. I read a lot. I exercised more. I took up writing again. However, after the first three months of confinement, we did have a crisis because my guide dog Raquel started to get really anxious and kept scratching herself.

ZARÍA: I was able to handle the first stages of the pandemic well. My autism was an advantage, although it is considered one of the risk factors for getting COVID. For me, my autism comes with various repetitive behaviors that have to do with cleaning, which are part of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Having these behaviors, I felt like I’d been handed the rules of the “pandemic game,” and as an autistic person, I was equipped to follow them.

PAMELA: Not being able to see each other and having to do everything online definitely made an impact. It was manageable for me because deaf people are used to the loneliness that comes with having communication barriers. I have built my own world, and loneliness is now a companion of mine.

ZARÍA: For me, the isolation stage hasn’t ended. I long to see trees and the horizon, sense the sky overhead, but it just isn’t safe for me to go out. Once again, those of us with disabilities are being left behind.

The kitchen

The women who participated in these facilitated conversations said the pandemic has changed the way they acquire and prepare food.

CRISTINA: Due to the strict isolation regulations enforced in the Dominican Republic at the beginning of the pandemic, people like me could no longer count on having assistants who could come to the house during the day to help us cook, wash, or clean. Many people had to ask someone to move in with them to provide them this support, but not everyone had a family member available to do that, which created a lot of uncertainty and a variety of problems.

KARINA: My husband has a 12-year-old daughter who lived with us for two months at the beginning of the pandemic. That was when Spain was in a declared state of emergency and I was going to radiation therapy at the hospital every day. We had to try to make the situation as comfortable as possible for all three of us, deciding together what we should do and what to cook.

Margareth Durán Vaca lives in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, and is a member of the Association for People of Short Stature of Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Photo courtesy of Durán Vaca with illustration by Giovana Fleck.

MARGARETH: For everyone living at my house, it was very difficult to go to the market. My daughter's father and his family would bring me food on a weekly basis.

PAMELA: Because of the need to isolate myself, I started buying everything online, because in the U.S., I can. I have internet access and shopping online actually works. Even though I am by myself here, I can do online chats and communicate with an interpreter 24 hours a day. Here, all of that has worked during the pandemic, but it hasn’t in my home country of Chile.

Solidarity as a way to fight the pandemic

The women who took part in these conversations have their own antidote to discrimination.

PAMELA: Having a support network is essential to me, as someone with a disability who is an immigrant and a woman. My identity is intersectional and the discrimination I face is more profound as a result. We are all capable, but those of us with disabilities face barriers constructed by society.

ZARÍA: People don’t want to understand that, because it’s easier for those of us with disabilities to be marginalized. There are more people who are eugenic and ableist*. I’m saddened by society’s lack of commitment to those of us who are their “sick”, who are their discas** (people with disabilities). My rage and belief in the solidarity of the disability community keeps me going.

CRISTINA: Many women have been marginalized without even leaving home, studying or working. When we come together and see that we can fight for our right to have the type of life that we want, both the individual and the collective are more powerful. Working together this way, each of us has a much stronger voice. There is strength in unity.

*“Ableism” refers to ways of discriminating against and constructing taboos around people with disabilities, generally to consider them inferior, of less value and/or infantilize them. “Eugenics” refers to ways of eliminating people with physical characteristics associated with being “weak,” in order to make the human race “healthy” or “strong.”

**In Spanish, “discas” is a way to say “people with disabilities.” It’s often used in common speech by people with disabilities to refer to themselves.

“Persisting in the Pandemic: Conversations between Latinas with disabilities” was produced with support from the International Center for Journalists and the Hearst Foundations as part of the ICFJ-Hearst Foundations Global Health Crisis Reporting Grant. The grant also provided mentorship and editorial support from Mexican journalist Priscila Hernández Flores, who specializes in reporting on human rights with an emphasis on diversity and disability. The women who participated in this project interviewed each other and guided their conversations. This article is the third of a four-part series. The interview quotes included in this article have been edited for clarity and brevity. The first article of the series provides context about the rights of women with disabilities in Latin America during the pandemic. The second story details their experiences leaving the house during the pandemic and the fourth expands on the methodology used for this project.