Trinbagonian writer Lisa Allen-Agostini, whose book ‘The Bread the Devil Knead’ has been shortlisted for the 2002 Women's Prize for Fiction. Photo by Paula Obe Photography, used with permission.

The Trinidad and Tobago-based author Lisa Allen-Agostini has been writing ever since she's known herself. Yet, despite her skill and substantial body of work, mainstream publishing recognition mostly eluded her, that is, until her most recent novel, “The Bread the Devil Knead” (released almost a year ago and published by the independent UK publishing house Myriad Editions), was shortlisted for the 2022 Women's Prize for Fiction.

In it, Trinidad comes to life. Scenes that are both colourful and real, that you can only see playing out in a post-colonial city like Port of Spain, are rife throughout the book. It also helps that the novel is written in local parlance: Trini-isms abound, submerging the reader in a vernacular that feels so authentic it's like you're there with the characters. Whether it's the complicated and spirited heroine, Alethea “Allie” Lopez, who is a victim of domestic abuse, her violent live-in boyfriend Leo, the boss man she's sleeping with or her motley crew of friends, the reader lives through the experience with them.

In an April 9 BBC Front Row interview, Allen-Agostini talked about writing cinematically, and it's true; reading her book, my muscles tense up at the possibility of Leo turning ugly; my breath catches in my throat when Allie comes to terms with the truth of her past — I might as well be watching a Hitchcock film. Over the course of the next few days, Allen-Agostini and I chat, WhatsApp and email about the book, the shortlist and more …

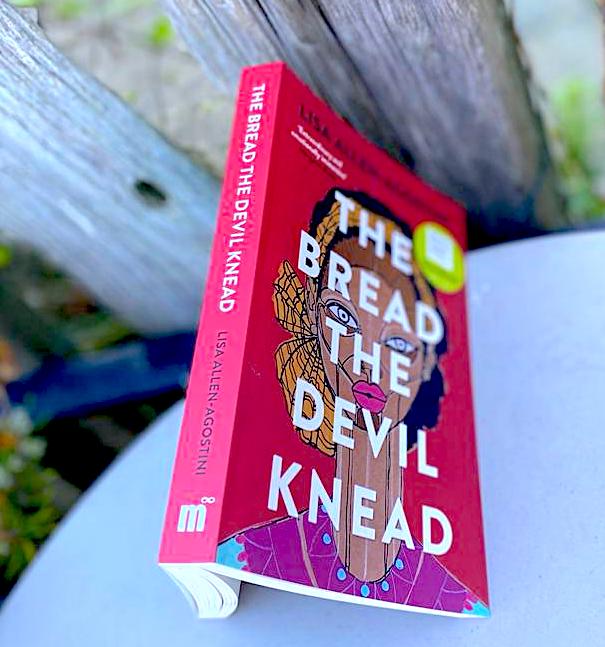

Lisa Allen-Agostini's novel ‘The Bread the Devil Knead,’ which has been shortlisted for the 2002 Women's Prize for Fiction. Photo by Corinne Pearlman, used with permission.

Janine Mendes-Franco (JMF): Congrats on the book — not your first by any means, but the first for which you’ve been shortlisted for such a prestigious writing prize. What does the honour mean to you?

Lisa Allen-Agostini (LAA): As my friend and fellow writer Anu Lakhan said, even if I don’t win, forever after I’ll be a writer whose book was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction! I’m in the same category as Margaret Atwood, who was also shortlisted for this prize in the past. I’m waiting to see what happens. God promised the book would go far, and stay in print for a long time. I think he’s very keen on getting its message out: that women don’t have to stay in abusive relationships, that they can be delivered, that they can find loving support and change their lives. The shortlisting helps that happen and so I’m grateful for it.

JMF: You’ve said that the character of Alethea came to you while doing a writing workshop with author Wayne Brown in the mid 2000s. I think it’s brilliant that you’ve cast the “red woman,” who in Caribbean culture is typically put up on a pedestal thanks to her fairer skin, as a victim of horrific violence — but you don’t particularly like her. Why?

LAA: She’s blunt and bitchy— I mean, the things she says about the other characters are really awful and she’s kind of cold and distant in some ways. And I’ve always felt that for a woman to walk away from her family as she did seems to make her less sympathetic even when she’s doing it to save her own life. I am shocked when people say she’s one of their favourite characters. And yes, the point of the story is that she looks like this “browning with tall hair,” which Professor Patricia Mohammed has theorised as the epitome of sexualised Caribbean femininity — men want her and women want to be her — but in private she has had this terrible family history and she lives in hell. But she red, so nobody sees that. The novel is a way to show that our assumptions about a woman’s life may be wrong, and that we may all possibly be living through terrible things, and that all women can be subject to abuse, regardless of class, caste or colour.

JMF: Let’s talk about violence in the local context: childhood violence, both corporal and sexual (now a front page story once more because of alleged abuse in children’s homes); violence linked to race in terms of colourism and how people are treated. How do you think we should be dealing with issues like these in order to effect positive change?

LAA: Of course we should talk more about violence across the board and stop pretending it only happens in certain classes of people. I tell young people when I talk to them about mental illness that if they had a “sore foot” (a Trini expression for an ulcerated wound) but that they kept it covered up and never treated it, it would only get worse and worse and eventually cause the foot to rot and fall off. The same is true about the endemic violence we face here. Across all ages, races, classes. We are born and raised in violence because of our national history. We minimise the effects of African chattel slavery here, say it was “mild” compared to Barbados, Jamaica, Cuba, or Brazil — but it was still horrific. And those lessons are in our DNA. We have to talk about it before we can begin to untangle its generational effects and heal.

JMF: Over the past few years, the issue of domestic violence has been consistently grabbing headlines in Trinidad and Tobago. In the book, you break down the situation into a series of cause-and-effect scenarios, painting a picture of the emotional rollercoaster that is domestic violence and perhaps giving the “Why don’t you just leave?” crowd pause. In real life, why do you think we’re still grappling with very basic approaches to the issue? Why aren’t women being better protected? And really, why aren’t men being called to account for their behaviour?

LAA: I think there has been some change in systems and legal protections. For example, it’s no longer legal to beat your wife, even if it is still tacitly approved of by many men across the board in my experience. Violence against women is an intractable problem that has in fact been made worse in a way because women have changed through feminism and men, by and large, have not. So a woman will get box in her mouth because she feels she has the right to say things to her man and he doesn’t feel she has that right at all. So there’s a gap in understanding and a gap in lived experience between men and women. It’s no good telling men, ‘Get over it’ without giving them the tools with which to understand how to get over it; or telling women, ‘Be independent’ when they still have to live with men who don’t really want independent women. It’s complicated and difficult and honestly, I don’t know what the answers are but I am sure that we need to talk about it more honestly and more frequently.

JMF: There’s no hero in the book. No one’s coming to rescue Allie, and by your own admission, she’s not really a heroine herself. Is there an underlying message you want readers to take away?

LAA: The main character is delivered. If you look at the structure of the book, you’ll see that she cries out to God and her life begins to change — and in the end she’s delivered and nobody can explain how. People in secular modern society mock the idea that God can deliver someone from a terrible situation but I’ve seen it. I’ve lived it. I am not a survivor of this kind of violence but I’ve experienced other kinds of deliverance, and there are many who can testify that, indeed, they have been delivered from terrible situations where they could have been killed. I would really like women to know that they don’t have to stay in abusive situations, and that even when things look absolutely hopeless, God is there and he can help them.

Writer Lisa Allen-Agostini; photo by Paula Obe Photography, used with permission.

JMF: Despite your strong faith that God will — and has — brought you through things, there was a point at which you were on the verge of turning your back on writing. Why — and what happened to change your mind?

LAA: After many years as a writer of poetry and prose, I had given up. I just wasn’t getting though, not in the way I thought I deserved after decades of hard work and sacrifice. I was what they call a “respected writer” and “widely published,” and I had had some international success with a Young Adult (YA) novella and a book of poems and a collection of short fiction which I had co-edited. But the big success — winning international prizes, getting an agent, selling a book to a really big publisher — kept eluding me. I gave up. I said, “God, I’m done. I am not doing this anymore.”

Not long afterwards, two things happened. First was the news that a manuscript of mine had been awarded in the CODE Caribbean YA Lit prize administered by the Bocas Lit Fest. The other was that Margaret Busby called to invite me to contribute to New Daughters of Africa. Busby is the doyenne of Black British publishing; when she says you’re good, trust and believe that you’re good. That she would personally reach out to ask me to contribute blew my mind and made me realise that I wasn’t yet done with writing. It’s significant, too, that the manuscript that was awarded (it was published as “Home Home” in 2018) was about a young black Trini girl with mental illness; and the anthology New Daughters of Africa is black women’s writing from the African diaspora. It gave me great clarity about what my mission is as a writer, what I had been sent to do and whom I had been sent to reach.

JMF: You describe yourself as a Trinidad writer. What does that definition mean to you?

LAA: I chose to stay in Trinidad and Tobago despite the fact that it would hurt my chances at international success. It’s mad to stay here and hope someone will publish your book out there; and it rarely happens, relatively speaking. But I stayed and I continue to stay. I also call myself a Trinidad writer because I write about this place and its people, in its voices. I write about its traditions and its vagaries and its joys and horrors. I write about its past and its present and its future. It’s not that I’ve never written about anything else, but Trinidad and its people are overwhelmingly my theme and subject matter. My Facebook author page is literally @trinidadwriter because, of all the things I’m called to document or give voice to, it is Trinidad and its people’s stories that are the most urgent and compelling.

JMF: What do you think makes a “successful” writer? Is it being recognised, selling lots of books? Is it that feeling of having birthed something worthwhile? Is it the joy of the process?

LAA: For me success is being able to buy groceries and pay the light bill from what I’ve earned as a writer. (Maybe buy a car, build a house, too. I haven’t got there yet.) But also, there’s the kind of success that I have achieved: that my work is respected, that my voice is heard, that the books I have written have largely remained in print for many years, and that generations of readers may come to find something in a Lisa Allen-Agostini piece. Writing gave me life for many years and there was another success in that: the success of finely crafting words to diamond sharpness. I take great pleasure in that. When I know I’ve written the pants off a piece, that’s success.