In Myanmar, conversations about the military regime happen on Facebook. On the platform’s groups, pages, and individual profiles, the population is divided between democracy and military supporters. Every social media post carries evolving narratives that shape the makeup of the convulsed nation, yet mainstream media outside Myanmar have failed to report on them.

Myanmar researchers have dissected — by combing through Burmese social media — how pro-Junta citizens are justifying the military’s violence against civilians.

Why it matters

More than a year has passed since Myanmar’s military took over the country and arrested its democratic leaders and about 10,000 civilians. Dozens of people have been sentenced to death. The killings of more than 1,700 people, including children, have been attributed to the army. Hundreds of thousands of young people – students, professionals, and political activists – have fled to neighboring countries or are in hiding inside Myanmar.

Because the massive pro-democracy demonstrations were severely repressed last year, thousands of youth took up arms in what can be called guerrilla warfare. Many of them have received training from ethnic militias that have challenged the government for decades. Myanmar went through military rule from 1962 to 2011 — the year that it initiated a period of democratization before falling into the hands of the junta again.

The new, decentralized civilian armed resistance, which goes by the name “People’s Defense Forces” (PDF), is mostly funded by donations from the Burmese community. The country’s military supporters, who tend to be on the conservative side of the spectrum, are attempting to discredit and justify violence against the armed resistance.

How everyday usage of Facebook works

- In 2021, Myanmar’s junta banned Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and people access these sites using VPNs. Military sympathizers support this measure as a means of disrupting pro-democracy content on the platform, but they also use VPNs, thereby breaking the rules of their leaders.

- The Tatmadaw is seeking to ban the usage of VPNs altogether and has cut off internet access in resistance strongholds.

- A large portion of pro-military discourse is based on misleading and false content. Propaganda is used to undermine reporting of human rights violations and mass atrocities. Content also varies from happy-go-lucky videos of dancing soldiers to violent and humiliating recordings.

- Pro-military people tend to not share posts they agree with, but rather copy-paste the content and publish it as separate posts. This helps them avoid Facebook’s content moderators.

- Pro-democracy and pro-military promoters tend to use different fonts. Mobile users made the switch from Zawgyi to Unicode font for Burmese, but most military supporters continue to use Zawgyi, making it unreadable for other users whose phones cannot decipher it.

Myanmar's pro-military narratives

1.“The People's Defense Force is a terrorist group and harms people”

Since the coup in 2021, the Tatmadaw, as Myanmar’s military is known, has been accused of committing brutal human rights violations. In January 2022, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, stated that the military has “a flagrant disregard for human life.” Many civilians – who are not necessarily linked to the armed resistance – “have been shot in the head, burned to death, arbitrarily arrested, tortured or used as human shields”. For example, last December, a military truck rammed into a crowd of demonstrators, killing five people. Two days later, the military was allegedly involved in burning 11 people alive in the Sagaing region.

Facing mounting repression, thousands of pro-democracy civilians have banded together to defend themselves and counterattack. In the past few months, they have targeted police stations, military trucks, and small units and have killed military and police personnel. Many Myanmar people continue to raise funds to support the PDF.

This narrative leads to more dangerous ones, such as those that justify lethal violence against the PDF. Lately, this has become more extreme as some army supporters believe that the Tatmadaw has “grown soft”.

How this narrative plays out on Facebook

April is the month of Thingyan, a water festival in Myanmar. During the festival, people splash water at each other. Some people give out food. The post claims that the PDF has put acid in water bottles and that it is poisoning boiled eggs. The post does not refer to the PDF by name, but it is evident that it is talking about them (in the usage of the words “destruction and disturbances”). Comments and people who shared the post warned others to be careful about alleged PDF attacks. More analysis here.

See more analysis of media items. Some Facebook users ask that the army disregard international community standards (MM_124), others blame pro-democracy supporters for disturbances in education, and alleged soldiers say that the military is not appreciated enough.

2.“Young people who join the PDF are misguided and immoral”

Junta sympathizers lean toward traditional values like organized religion, nationalism, and formal education. When the country started its democratic shift in 2011, some conservative people felt threatened. In the country’s 2020 general election, pro-democracy activist Aung Suu Kyi’s party won by a landslide, but a few months later, the Tatmadaw deemed the results illegitimate and annulled the vote altogether.

“Pro-military supporters, who are nationalist and extreme Buddhists, feel threatened by the progressiveness among Burmese people as the country shifted into a civilian government. They feel secure in their daily lives of religious activities while living under a dictatorship that holds the same values,” our researchers say.

The narrative blaming youth for perverseness is closely linked to the discourse that says “Only military supporters value Buddhism and care about the nation” and to Islamophobic sentiment.

Junta sympathizers accuse young activists of being under the influence of drugs, alcohol, or Western values. This narrative also encompasses sexist connotations about the sexual lives of young women and provokes sexual violence.

How this narrative plays out on Facebook

This pro-military Facebook page shared two pictures: the first photo shows a pregnant woman, an alleged member of the armed resistance, and the second portrays Aung Myo Min, the Minister of Human Rights from the National Unity Government (NUG), the political entity of elected politicians from the 2020 elections, now in exile. The text of the image says that “the pregnant PDF woman and the gay minister” are going to appear in a pro-democracy film. More analysis here.

See more analysis here of posts that claim that Buddhism is no longer respected, that education promotes Islamic and liberal values, that the PDF is dismantling the educational system, and posts that promote violence against women in rebel groups.

3. “The military regime needs leaders who will take stronger actions against the pro-democracy movement”

After the coup in 2021, army sympathizers welcomed the Junta and the new military council led by Min Aung Hlaing. However, a year later, some have expressed their dissatisfaction with the regime for being too soft or indecisive against the pro-democracy movement, despite the violent crackdowns. This view is largely motivated by news of soldiers being killed in clashes against armed rebel groups. Other military supporters say that the army could easily destroy the PDF if it had the will to do so.

How this narrative plays out on Facebook

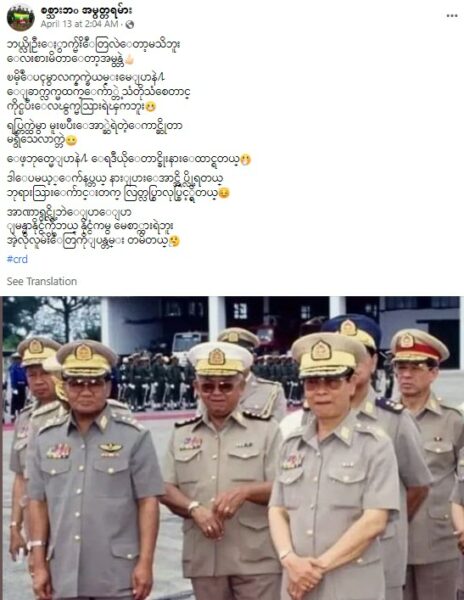

A pro-military Facebook page shared a nostalgic post about Myanmar’s past dictatorship. The photo shows previous dictators (former Senior General Than Swe with General Khin Nyut) and the caption reads that the country was peaceful enough during those days. It ends by saying that the author would like those leaders to return. This post implies that the country is losing its stability because of armed resistance and that the current leadership is too soft with its opponents. More analysis here.

See more posts that say that the current regime is too weak and which reminisce about the previous dictatorship.

View our entire Myanmar dataset

More related narratives to explore:

- “Violence against pro-democracy supporters is justified”

- “Facebook is violating the freedom of expression of pro-military people”