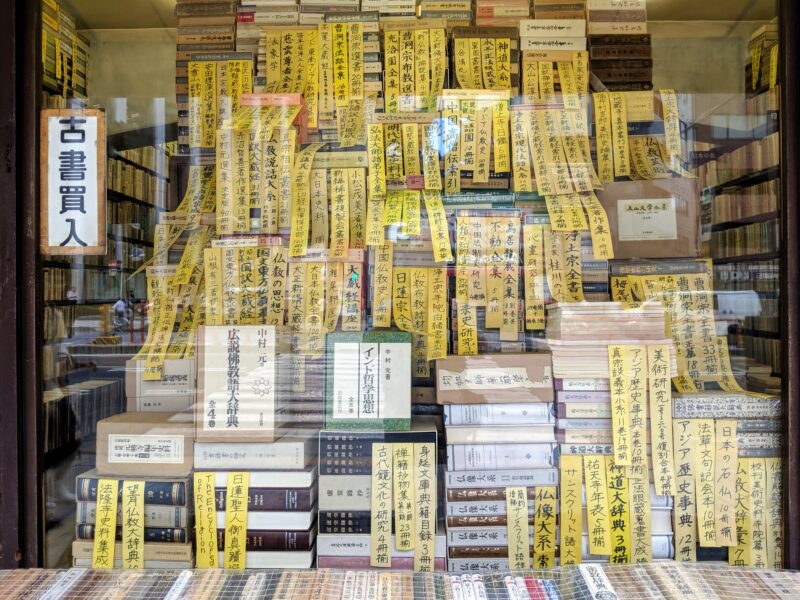

Used-books store in Jinbocho, in Kanda, Tokyo. On annual visits back to Japan, I set aside several days just to visit bookstores. I visited this bookstore 872 days ago. Photo by Nevin Thompson. (CC BY-NC 2.0)

It has been 879 days — 2 years, 4 months, and 26 days — since I last set foot in Japan. This is my longest absence from the country in 27 years — 10,009 days, to be exact. Thanks to Japan's strict, and, in some ways, incomprehensible COVID-19 travel restrictions for foreigners, it's hard to say when I'll be able to return. On the other hand, others stuck outside of Japan have it far worse.

Japan has effectively banned the entry of non-Japanese visitors to the country since the beginning of April 2020 and the start of the pandemic. Where the country welcomed at least 32 million visitors in 2019, by the end of 2021 that number had shrunk to just 190,000.

In response to the emergence of the COVID-19 Omicron variant in late November, unelected bureaucrats imposed even more draconian entry restrictions. For a few days last December, no one could enter Japan, leaving Japanese citizens stranded outside the country until elected politicians intervened.

However, it remains practically impossible for any non-Japanese person besides permanent residents (which I am not) to enter the country. Even if I could persuade the consulate in Vancouver to allow me to travel to Japan, I would still need to quarantine with my family for seven days in an approved hotel, at my own expense. With a family of four this is very expensive, potentially very claustrophobic, and very boring, and also cuts into what little time we might have to spend in the country in the first place.

I'm not allowed into Japan, anyway, so, I continue to count the days.

Toro Nagashi (Lantern Festival), Tsuruga Bay, Japan, 899 days ago. Each year at the end of Obon, the annual festival of the dead, lanterns symbolizing the ancestors are set sail for the afterlife. Photo by Nevin Thompson. (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Almost every non-Japanese person who spends a significant amount of time in the country marks their “Japanniversary” each year. For me, it's September 6, 1994, the anniversary of my arrival in Japan. I remember flying over the glittering sprawl of Osaka in the early evening, riding a wine-colored Hankyu train with green seats and faux-wood paneling to Nishinomiya, and my first meal, tuna-fish onigiri (rice ball) from Lawson.

I relocated from Japan with my family, including a dog, 3,506 days later, on Tuesday, April 12, 2004. I had decided to move to Canada in April 2004 in hopes of doing something else besides teaching English conversation. But I had few prospects “back home,” and very little money. I thought I would never be able to return to Japan. I became depressed.

Happily, 759 days later, we returned to Japan. Ever since then, I've been able to spend at least part of the year in Tsuruga.

What is my connection to Japan? Why do I feel the need to return to Japan regularly, in order to feel whole? I know I'm not the only person to feel this way.

I don't return to “Japan.” Instead, I return to Tsuruga, a small city on the Japan Sea Coast that most Japanese people couldn't find on a map. My mother-in-law lives there, as does my sister-in-law and her family. My sons are both Japanese citizens, and they need to maintain a significant connection to their country and their culture. The family graves are in Tsuruga, the family dead come home each August to Tsuruga, for Obon, the festival of the dead. We try to be there for them.

In our home in Canada we speak the Tsuruga dialect, which can sound strange to other Japanese people living here in Victoria. Tsuruga has its own flavour of soy sauce and miso, and rice grown right in the neighbourhood. There are hot springs nearby, beaches, and a swimming hole up in the hills.

The Kuroko River swimming hole, in Tsuruga, Fukui. I last visited here 895 days ago. Photo by Nevin Thompson. (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Arriving in Japan in my early twenties, I matured into an adult there. Many of my tastes, interests, and sensibilities were deeply connected to Japan, such as the taste of the soy sauce, miso and booze, all local to the small rural town where I lived.

TV shows, newspapers, magazines, libraries — on annual visits back to Japan, I set aside several days just to visit bookstores.

Until COVID-19 effectively banished me from the country, Japan had been a part of who I am, my identity. But the connection is fading now, the attraction harder to explain.

Many others, however, have it far worse than I do. Entire lives put on hold or destroyed by Japan's COVID-19 travel ban. Between 150,000 and 370,000 students and workers are blocked from entering Japan, giving up jobs, scholarships, and academic careers.

Families have been split up by seemingly punitive, cruel, and nonsensical border entry regulations.

Your Irony of the Day: the Japan foundation is funding a multidisciplinary conference on “COVID and Japan,” but because Japan won’t admit foreigners, they’re holding it in . . . Bangladesh.

— John Whittier Treat (@johnwtreat) January 20, 2022

We're fortunate, though. While we would dearly love to see our family in Tsuruga as soon as possible, my wife and I can still afford to wait, absorbed in the life we have built on this side of the Pacific.

While the Japanese public is largely unaware of the issue, Japanese businesses, which had been increasingly relying on immigrant workers before the COVID-19 travel ban, are becoming impatient with the Japanese government. Protests against Japan's COVID-19 ban are also being organized around the world.

In response, the Japanese government has let in just a few students. Some politicians are suggesting that entry restrictions be relaxed in the coming months.

I'm still counting the days. Can I return to Tsuruga for the start of summer vacation in 148 days? Or will I need to wait for winter holidays in another 316 days? Or, will I even be able to get in this year at all?

However, most people with work, school, or other connections to Japan must wait. Or must make other plans.

2 comments

From the other side of the glass being in Japan during this pandemic, it’s telling how the average Japanese citizen doesn’t care that foreigners are banned.

Thanks for reading, and thanks for the comment. Yes, it’s a bit disheartening how little support there is in Japan for ending the travel ban. As you well know, non-Japanese people are everywhere. In Tsuruga, NJ work in restaurants as servers, and in the back. And also in food processing, at textile mills, at chip factories, in care homes. And of course as teachers and instructors.