Wordle is everyone's favorite word game. Screenshot from video by CBS Sunday Morning.

Wordle, the minimalist online game taking the world by storm, first entered our lexicon in October 2021. That was when Josh Wardle, a Brooklyn, NY-based software engineer, decided to make the game available to the public.

Wardle initially designed the word-guessing puzzle as a gift for his partner, but after it proved popular with family and friends, he placed it on a simple public website. On November 1, 2021, just 90 people had played the game. In the two months since then, the game has attracted hundreds of thousands of fans and become a household name. Its emoji-based result reports — stacks of colored squares representing how many attempts it took to guess the five-letter word — have flooded our social media feeds.

Wordle has captured our imagination to such an extent that it has been dubbed “the sourdough starter of Omicron.” But why do we love it so much?

Wordle is the sourdough starter of Omicron.

— Emily Coleman (@editoremilye) January 14, 2022

Why is everyone mad for Wordle?

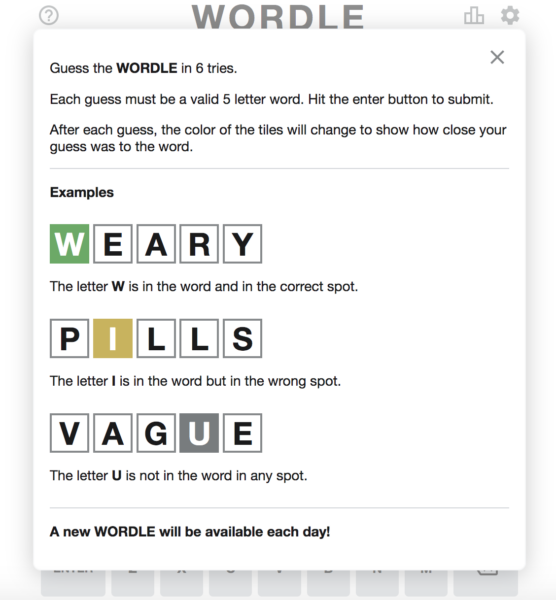

The game's success has been attributed to its simplicity: it asks you to guess a five-letter word, and gives you six tries, showing you whether any of your chosen letters are in the secret word and whether they are placed in the right position.

Some have also praised the game for being a once-a-day affair, meaning it only takes a few minutes of your time and does not send you annoying reminders, show you ads, or invite you to compete with other players (though it does show you your personal track record).

Screenshot from the Wordle website with simple directions for how to play the game.

“I think people kind of appreciate that there’s this thing online that’s just fun,” Wardle told The New York Times in an interview. “It’s not trying to do anything shady with your data or your eyeballs. It’s just a game that’s fun.”

On February 1, the game's fans woke up to the news that The New York Times was buying Wordle for “an undisclosed seven-figure sum.” Wardle himself shared an emotional post on Twitter, saying he was “thrilled” about the deal and adding that the game “has gotten bigger than I ever imagined”:

It has been incredible to watch the game bring so much joy to so many and I feel so grateful for the personal stories some of you have shared with me – from Wordle uniting distant family members, to provoking friendly rivalries, to supporting medical recoveries.

On the flip side, I'd be lying if I said this hasn't been overwhelming. After all, I am just one person, and it is important to me that, as Wordle grows, it continues to provide a great experience to everyone.

Though the newspaper promised that the game would “initially remain free,” many worried that the purchase would soon leave them without their daily moment of linguistic zen. However, some users noted that the game could easily be saved to a local server and remain available free of charge.

A world of Wordles

What's even more exciting about Wordle is that the code behind it can be adapted to work in a variety of languages and different contexts. More programming-savvy fans have already gotten their hands on the code and re-engineered it into every imaginable variation.

Wordles of the World (hosted on gitHub) is one of the more comprehensive listings of the game's incarnations in different languages. It contains a whopping 313 entries in 91 languages and proclaims its goal as being “threefold: having fun, celebrating language diversity, and exploring playful creativity.”

Wordles of the World is an ever-growing #multilingual list of ‘#wordle’ games from all over the world, aiming at being as comprehensive as possible.

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Have fun playing with your language(s), and remember: una lingua numquam satis est. 🗨🌐💬https://t.co/EM4tdxyOyX

— Júda Ronén (@JudaRonen) January 24, 2022

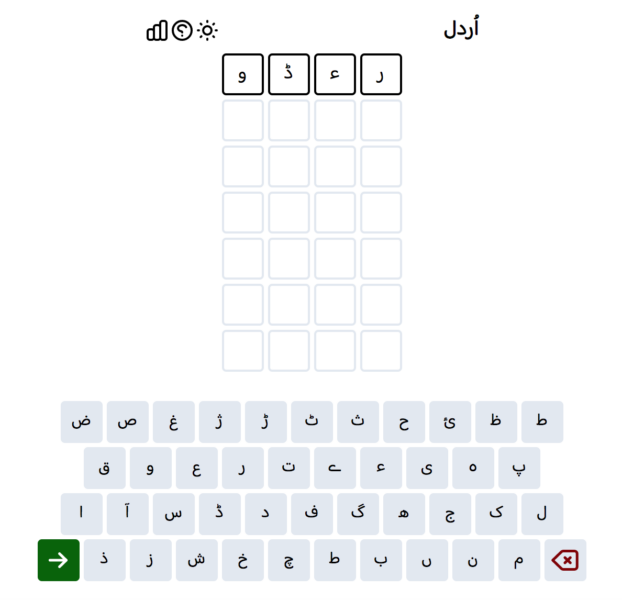

The Wordles on the list range from Belarusian and Cornish to Filipino and Kazakh, but also include versions in Klingon and American Sign Language (this one bears the name Dactle). Some languages, like Ukrainian, have more than one Wordle option: there's Slovko, Kobza and Wordle in Ukrainian to choose from.

Wordle in Urdu. Screenshot from Urdle.

Playful revival of indigenous languages

The game's popularity has also created new opportunities to promote indigenous languages: a Maui-based academic and language activist Keola Donaghy created a Hawaiian-language version called Hulihua to mark the start of “Mahina ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i” (Month of the Hawaiian Language).

Donaghy used open-source code initially released by Hannah Park and later modified by Aidan Pine, a linguist and software developer from British Columbia. Pine created a version of Wordle for the Gitksan language, an indigenous language spoken by the Gitxsan Nation in northwestern British Columbia.

There have also been other playful reimaginings of Wordle, including Eldrow, which gives you a clue word and asks you to guess what the previous word in the row above would have been, and Absurdle, an AI-based “adversarial” version that “is actively trying to avoid giving you the answer.”

There's also Lewdle, which, you guessed it, is based on a vocabulary of exclusively obscene and lewd words, and Custom Wordle, which allows you to make your own game by inputting a word for others to guess (this one has proved popular in school classrooms).

In a world where our daily existence is oversaturated with words and with so many sources of information vying for our attention, it's sometimes nice to exhale, set aside your social media feeds and spend five minutes meditating on a single word — doubly so if that word is in your native language.