Photograph of the town of Accompong in the parish of St. Elizabeth, Jamaica, in the early 20th century. Unknown author, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The relationship between Jamaica's Maroon communities and both colonial and post-Independence governments, remains complex. Now, a turn of events in the first week of January suggests that the Maroons may be adopting a new and more assertive stance; that many Jamaicans — with their incomplete knowledge of the key historical role Maroons have played — are ambivalent over their current status, and that there is considerable disquiet on the part of the government over the Accompong Maroons’ leadership.

There are four officially recognised Maroon settlements in Jamaica, divided into two groupings: the Leeward Maroons on the western side of the island, and the Windward Maroons to the east. The National Library of Jamaica describes their origins, which “date back to 1655, around the time when Tainos and Africans who were freed by the Spanish took to remote parts of the island for refuge from the English invasion and to establish settlements”:

The Jamaican Maroons are often described as enslaved Africans and persons of noticeable African descent who ran away or escaped from their masters or owners to acquire and preserve their freedom. […] From the second half of the seventeenth century to the mid eighteenth century, the Maroons developed into a formidable force that significantly challenged the system of enslavement imposed by the English. Though great controversy surrounds the terms of the treaties that they signed with the English, their role in undermining institutionalized slavery and cultural traditions are prominent parts of the history and heritage of Jamaica.

Accompong, situated in St. Elizabeth, western Jamaica and is named after the leader who founded it: Accompong was brother to Quao, Cuffy, Cudjoe and Nanny, the only girl and a national hero of Jamaica. The village was founded in 1739 on land given to the Maroons as part of a peace treaty with the British, and is home to the island’s most high-profile Maroon community.

Descended from the Akan (Ashanti) people of West Africa, the Accompong Maroons hold an annual ceremony on January 6 to commemorate the signing of the peace treaty and the establishment of the town and this year, took place with the usual large crowds in attendance, despite a warning from the Jamaica Constabulary Force that it was not in accordance with COVID-19 restrictions.

Publicity surrounding the event centred around its charismatic and university-educated leader, Maroon Chief Richard Currie, who at 44 represents a departure from his older, more conservative predecessors. Elected in March 2021, Currie has established a strong presence in Accompong, and apparently a good following. While some Jamaicans, both within and outside the community, find him divisive and aggressive, he also has admirers who see him as a strong, principled leader.

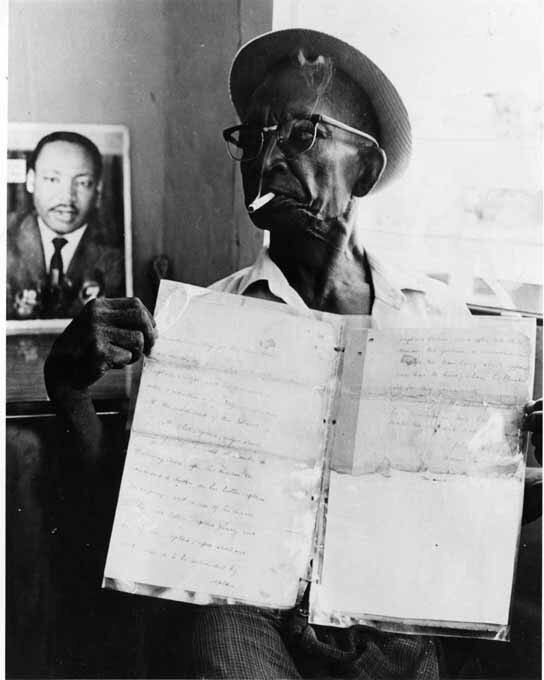

Accompong Maroon icon, Henry ‘Mann’ O. Rowe, holding the Maroon Peace Treaty. Behind him is an image of Martin Luther King, Jr. Image courtesy the National Library of Jamaica, used with permission.

When the January 6 event ended on a sour note, with a patron being killed by an off-duty policeman, the social media-savvy Chief Currie expressed his shock and regret on Instagram. On his Twitter account, Currie describes himself as “Head of State of Cockpit Country,” attesting that “Maroons are an Indigenous People with a sovereign republic predating the 1738 British Treaty.”

Such assertions have been a source of controversy and public debate over the years, as Accompong has its own Constitution. The debate has now been revived. At a January 9 security press briefing, Prime Minister Andrew Holness was asked about the issue of Maroon sovereignty and his administration’s decision not to fund projects in Accompong. In response, Holness alluded to “some threats that the average citizen looking on might think is innocuous,” vehemently asserting:

Jamaica is a unitary sovereign state. There is no other sovereign authority in Jamaica other than the Government of Jamaica. I want that to be absolutely clear. None. And under my leadership, not one inch of Jamaica will come under any other sovereign authority.

Addressing the journalist who had asked the question, Holness continued:

What you are asking would be for the Government of Jamaica to take taxpayers’ money and grant funds to fund another government…are you crazy? Really? Do you know what you’re asking? This is the stuff of how guerilla wars come and states break down. Wake up, Jamaica! Don’t court foolishness and problems. Wake up! People have died as a result. And you expect me to stand there as prime minister and fund activities that could lead to the breakdown of our state? Never!

Currie countered by sharing a January 6, 2019 tweet in which the prime minister described the treaty as “between two sovereign nations”:

Maybe the JLP loyalist should go clear this up with their PM so he doesn’t make Jamaica look so uneducated about the illustrious history of the #Maroons. We protected the island from invasion yet you wish to disrespect those who shed blood for this island. The world is watching! pic.twitter.com/3bxHgLu8kp

— Chief R. Currie (@ChiefCurrie) January 11, 2022

Currie also made the point that Jamaica is a signatory to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Jamaican academics have differing views on Maroon-related issues. Professor of History at the University of the West Indies, Verene Shepherd spoke to the question of Indigenous rights:

Maroons are considered Indigenous Peoples and they have rights under the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Please look up that Declaration.

— Verene A. Shepherd (@VereneAShep) January 10, 2022

To underscore her point, Professor Shepherd added that the Maroons lived with Taino peoples:

Mr Moore-Minott is correct. Maroons have Taino blood. They fought together in the mountains against colonialism.

— Verene A. Shepherd (@VereneAShep) January 10, 2022

Jamaica's Taino cacique, Kasike Nibonrix Kaiman, has been supportive of the Maroons’ cause.

However, Professor of International Law at The University of the West Indies, Stephen Vasciannie, discussed the 1739 Treaty in a newspaper column, in which he stressed that “the foundation document for Maroon rights and duties does not support the sovereignty case”:

There was a provision on Maroon leadership in the Maroon lands and punishment of Maroons in the defined area could largely be carried out by the Maroon leader. Generally, the arrangements envisaged freedom and some special rights for Maroons in return for peace and loyalty, but they did not create a Maroon State […]

Both Jamaican and international law point firmly against the notion that the Maroons may be regarded today as an independent State. This conclusion is consistent with clear facts on the ground throughout Jamaica. Maroons accord generally with the laws within the country and conduct their affairs as Jamaicans. If the Maroons wish to be regarded as politically separate from the rest of Jamaica, they will have to make the case with clarity and precision.

They will need to demonstrate convincingly why the small Jamaican State, already struggling with the problems of small island development, should support a diminution in its size at the behest of another small unit which is physically part of the existing Jamaican State.

A “concerned citizen” expressed doubts in a letter to the newspaper:

Perhaps […] the colonel is determined to take his tribe where others before have not [while] the Cabinet has ordered the withholding of funds and support to any entity which claims to be a sovereign State.

However, a tougher stance is needed, especially when viewed in the context of last August when a stand-off ensued between an armed Colonel Currie, his loyalists, and the police resulted in the police retreating, thus saving likely bloodshed […]

Clear lines must be drawn and, if needs be, a law must be passed with strict rules which, if breached, will result in harsh punishment.

Colonel Currie cannot continue to function as a law unto himself. This foolishness just has to stop.

It did not stop there. The prime minister later invited the heads of the other three Maroon groups to a meeting at his office, leading cultural activist and university lecturer Sonjah Stanley to muse:

I wonder if this was a move to divide and conquer in post colonial Jamaica 👀—- Accompong's Currie left out as PM meets with maroon chiefs https://t.co/I63ofQDAzK

— Culture Doctor of Kingston (@SonjahStanley) January 21, 2022

While Currie expressed hope at dialoguing with the prime minister, he was disappointed that — although they had agreed to present a united front — his fellow Maroons leaders appeared to have changed their minds.

One reason for Jamaicans’ general ambivalence towards the Maroons is that some groups returned escaped slaves to the British at certain points in history (and in fact, captured National Hero Paul Bogle). On a recent television current affairs program, the host asked Accompong’s Ambassador if they should apologize for returning runaway slaves to the British?

If you missed #TVJAllAngles here’s one of the highlights:

Should the maroons apologize for returning runaway slaves?@djmillerJA explores with Ambassador Anu Tafarri Zion El. pic.twitter.com/ZzFxLylPOP

— #ClimateChange (@aneikaangus) January 27, 2022

The other critical element is the Maroons’ connection to Cockpit Country — an ecologically sensitive area that has been the subject of long-running debates between government, bauxite mining companies, residents, and environmentalists.

Despite the January 3 announcement that a smaller portion of the highly controversial Special Mining Licence (SML173) would be apportioned for mining, concerns remain, including that other areas in and around Cockpit Country may be targeted. Bauxite mining remains a source of unending pressure, stress, loss of agricultural land, and health concerns for local residents, prompting one climate change expert to tweet:

This Maroon business really gone way beyond the initial point though.

Ignore the noise. Focus. Protect the Cockpit Country.

— Gerald Lindo (@geraldlindo) January 22, 2022

There are also concerns over a forthcoming and quite significant UN-funded project in the area, in which the Accompong Maroons insist they should have input. The Holness administration has already reportedly instructed government agencies not to engage with or fund activities in the community while it is under its current leadership.

As things escalate, One Jamaican suggested:

Both the PM and Chief Currie need to lower the temperature of this discussion #TvjAllAngles

— Obika G (@kingofkgn) January 13, 2022

Personalities aside, unresolved issues and questions over the Maroons linger — many of them recurring over several years — for which ongoing dialogue appears to be the only answer. The current situation, however, appears to be mired in stalemate.