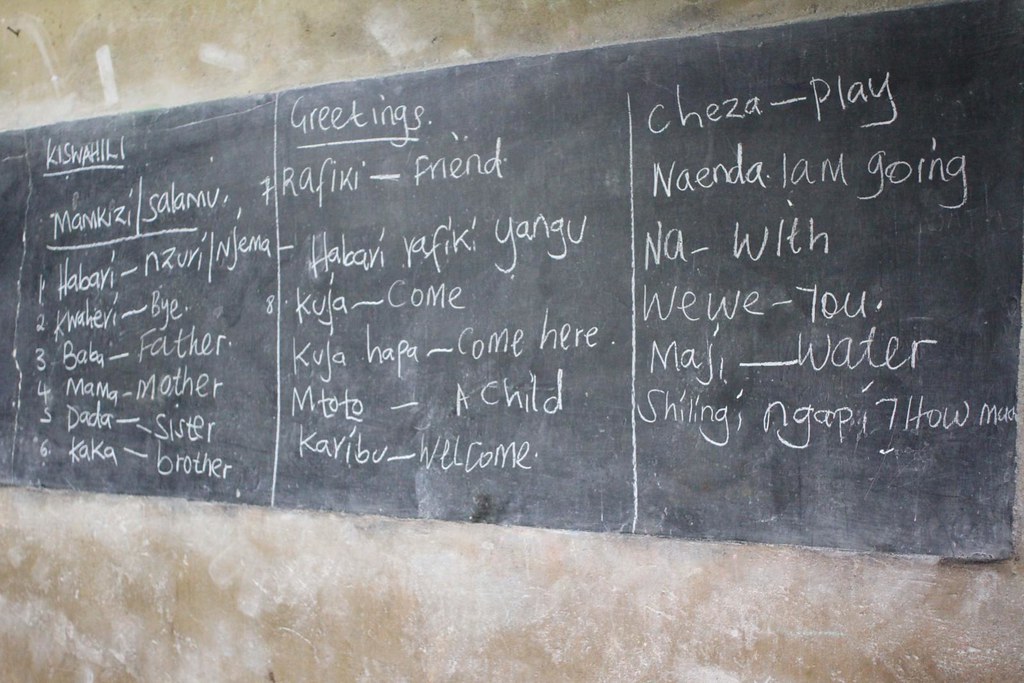

“Kiswahili phrases” by ultraBobban is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

In November 2021 during its 41st Session in Paris, UNESCO Member States declared July 7th World Kiswahili Language Day. Kiswahili — also known as Swahili — is a Bantu language native to Eastern and Central Africa where it's spoken either as a mother tongue or a fluent second language by an estimated 80 million people.

Despite its wide reach, many around the world are unaware of the significance and history of Swahili. Global Voices spoke with Hannah Gibson, a senior lecturer in the Department of Language and Linguistics at the University of Essex, about a new four-year project titled “Grammatical variation in Swahili: contact, change and identity” that she and her colleagues have launched to better understand present-day dialectal variations in Swahili.

In this interview, we hear from the project team: Hannah Gibson (University of Essex), Fridah Kanana Erastus (Kenyatta University), Tom Jelpke (SOAS University of London), Lutz Marten (SOAS University of London), Teresa Poeta (University of Essex), and Julius Taji (University of Dar es Salaam) about the aims and impact of the project, as well as the role of Swahili globally and in East Africa. They also speak on why the recognition of Kiswahili at a global level is important in helping more people take an interest in learning the language.

Global Voices (GV): What is the focus of this four-year research project?

Project Team (PT): This project looks at how the Swahili language varies depending on the various places where it is spoken, as well as the different groups of people who speak it. In addition to being the first language of some communities on the coast of East Africa, Swahili is used as a lingua franca by many others and now has over 100 million speakers.

With Swahili being spoken in so many diverse contexts, we expect there to be a lot of variation in how the language is used on day-to-day basis.

In the past, we know scholars have described some of the dialects on the coast. And more recently some of the “newer” varieties — such as Swahili spoken in DRC or Sheng — are being talked about. But there is no in-depth study of variation in present-day Swahili nor of the ways speakers use this variation for different purposes. That’s what this project aims to explore.

GV: What are some of the questions you hope to answer about dialectal variation in Swahili?

PT: Firstly, we want to gain a better understanding of the present-day variation in Swahili. And while traditionally the linguistic focus has been more on pronunciation and lexical variation (the way words differ in various dialects), we will focus on the structural differences — for example the different ways in which sentences are constructed.

The second set of questions we want to answer is how this variation is linked to the linguistic environments in which Swahili is spoke. Many East African contexts are highly multilingual, with people using several languages on daily basis. In our project, we ask how the contact between Swahili and various other languages in Kenya and Tanzania results in the languages influencing each other.

Lastly, we are interested in what these different Swahili varieties mean for speakers and their identities and how speaking a certain dialect may impact — or reflect — various societal issues.

GV: Who is undertaking this study? And why is this project important to you?

PT: The project is a collaboration between four different universities across three countries — Kenya, Tanzania, and the UK. Our team is made up of colleagues from Kenyatta University, SOAS University of London, University of Dar Es Salaam and University of Essex — each bringing their own set of skills and experience to the project.

We are very excited to embark on this study and to be able to focus on the role played by Swahili. Linguistic studies on dialects and variation in major languages tend to focus on European contexts or take the Global North as the starting point (for example through the study of English), so we are excited to be putting Swahili at the centre the study.

GV: How is this project significant for the current state and development of the Swahili language?

PT: The number of Swahili speakers is growing. So is the number of places where Swahili is used and taught. A better understanding of Swahili varieties has many uses and implications. For example, it can influence how the language is taught. It can help us to better understand how speakers use Swahili and what information they can access in it. It can also give us insights into what Swahili means for the speakers’ sense of identity and community and how this continues to change.

From an academic perspective, this study contributes to, expands and builds on the rich scholarly tradition of work on the Swahili language.

GV: When will the project be completed and how can people access the findings?

PT: The project is funded by the Leverhulme Trust and lasts for four years. Having just started in September 2021 it will be completed in August 2024. As well as the project website — to be launched soon — which will have regular updates, the broader findings will also be made available online.

It is important to us that any resources we gather are freely available to anyone interested in them and for people wanting to further work on the Swahili language.

GV: Last month, UNESCO declared July 7 as World Kiswahili Language Day what is/was your reaction individually and as researchers of the language to this declaration and recognition?

PT: We were excited to hear the news and we will celebrate Swahili with a project event on that day for sure!

GV: Why is this recognition important?

PT: It’s great to see an African language celebrated at a more international and global level — it is long overdue. Swahili as a language, its significance and history as well as its status today is unknown to many people around the world and this recognition can help us all to learn more about it – perhaps even get people excited to try and learn it too!

Our hope is also for Swahili to be celebrated in its complexity — with its many varieties and dialects, with the diverse groups of Swahili speakers for whom this language can mean different things and together with the varied and multilingual environments where it is spoken.

GV: What are the likely short-term and long-term effects of Swahili becoming the first African language to receive this honor?

PT: Hopefully, this can also be the start of an international celebration of many more African languages. Swahili is a major language and it is great to see it acknowledged and celebrated. It is also important it doesn’t end up being the sole representative of an entire continent but rather an example of the incredible linguistic diversity which surrounds it.

GV: How can people find out more about the project?

PT: Watch this space! We will hopefully be doing regular updates for Global Voices online. So we will be back to let you know how we are getting on.

2 comments

This is definitely an exiting project that I will follow closely being a linguistic scholar myself. Kiswahili is one of those unique languages that do not belong to anyone. Everyone receives it and customizes it to fit their own needs. Sheng will also be an interesting creole to investigate due to its rapid morphing.

Looking forward.

What a great project. The history of Kiswahili has really grown and it is a language worth this celebration. Am excited to do a research on how Kiswahili is interacting with technology, considering this new honor of being recognized and celebrated worldwide.