Chandra Kala slathers maard, a mixture of rice and water, on the threads to make them stronger. Image by Sudin KC via Record Nepal. Used with permission.

This article by Aishwarya Baidar was first published in The Record (Nepal); an edited version is republished below as part of a content-sharing agreement with Global Voices.

Shaded from the scorching heat of the Tarai sun by a bamboo-and-tin hut, Chandra Kala Dhimal places her glasses on top of her wrinkled forehead as she arranges threads, one string at a time, into a loom’s comb. She slides her feet into an alcove below the loom, tugging at two bamboo poles with her toes. Her hands move in unison, swiftly weaving the threads together. Veins pop like lightning along her slender arms as she presses thread against thread. Every day, the 65-year-old works for hours on her traditional wooden loom, a musical cling-and-clang ringing out across the hut. She is one of the last few weavers from the indigenous Dhimal community of Nepal still keeping traditional wooden weaving alive.

“It’s a difficult process which only a few of us in the Dhimal community can do properly,” says Chandra Kala, the sweat-soaked fabric of her blouse plastered against her back.

As modern weaving machines that are simpler to use and operable all year round become much more easily available, traditional looms for weaving tribal attire, like the kind Chandra Kala operates, are becoming harder to find.

Chandra Kala was 12 when her mother taught her “baojinka”, the process of weaving thread. She was often beaten by her mother if she was disobedient. “If I die, then who will teach you how to weave?” her mother used to say to her.

Her mother passed away soon after Chandra Kala turned 14 but by that time, weaving petani, a traditional Dhimal outfit, had already become her primary source of income as she never received a formal education.

“I learned to weave from my mother more than five decades ago,” Chandra Kala explains, “but none of my children want to learn those skills. They say it's too much effort.”

The traditional Dhimal art of weaving, passed down through generations, is now in danger of dying out. Like Chandra Kala’s children, who are laborers in the Nepalese capital Kathmandu, most young members of the Dhimal community have taken up other professions. Even those who do weave have adopted modern machinery.

“I […] prefer the machine because traditional looms are hard to work with and cannot be used during the monsoon as the pits fill up with rainwater,” says 54-year-old Ranga Maya Dhimal, a resident of Dapgachi, an Indigenous village that is home to the Dhimal community in Damak. “Chandra Kala is the only one among us who can still skillfully wield the traditional handloom.”

A photo of Chandra Kala Dhimal in her younger days. Photo by Sudin KC via Record Nepal. Used with permission.

According to Ranga Maya, she was able to weave 10 to 12 petani a year on the traditional loom but is now now able to produce 16 to 20 on her new, mechanized loom.

Dhimal women weave and wear petani, ankle-length black dresses with orange and white stripes representing the tribal pattern of the Dhimals, around the waist. Chandra Kala takes up to five days to weave a single petani and can finish four to five in a month—but she doesn’t work all year round. As most looms are out in the open, the alcoves tend to fill with water, rendering the looms unusable.

Petani woven by traditional methods are better and more durable, says Ranga Maya. Traditionally woven clothes tend to last longer, making them a more sustainable choice to modern alternatives. To the ethnic Dhimal, whose gods reside in nature itself, an aspect of their age-old sustainable coexistence with nature is also being lost alongside their tribal weaving process.

“The process begins by sowing the seeds of the indigo plant, known as solai in Dhimal dialect, which have been passed down to us by our ancestors,” says Ranga Maya. The leaves are harvested once the plant is fully grown, and boiled in water with thread to dye them. The dyed threads are rich in color and stronger. Once dry, they are detangled and made into spools. They become even more durable when slathered in rice water. The whole process can take about four days, after which they are woven into petani.

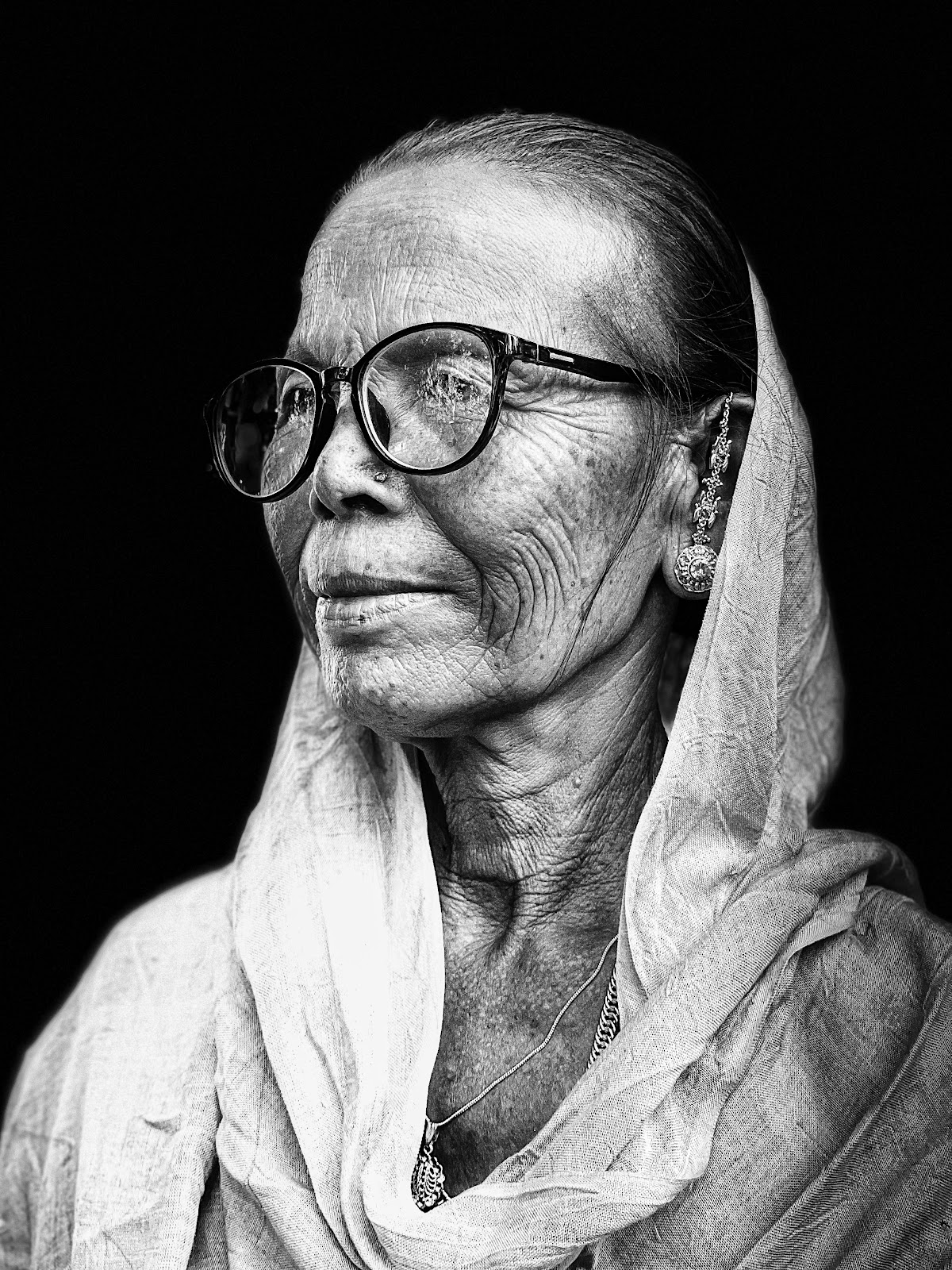

A portrait of Chandra Kala Dhimal. Image by Sudin KC via Record Nepal. Used with permission.

The entire process, passed down for generations by the Dhimal community, is a sustainable one, utilizing natural resources not just for the weaving but also for the dyeing. Hybrid seeds can be purchased in the market, but Chandra Kala says they make for poorer dyes.

“I have woven many clothes, especially for my relatives,” she says. In the past, Chandra Kala used to earn 200 to 500 rupees (1.7 to 4.2 United States dollars) for a petani. Now, she makes Rs 1,000 (US $8.4) per petani, but old age has caught up with her and she weaves less often due to her poor eyesight.

Ever since her husband passed away, Chandra Kala has taken care of her two daughters and two sons with the earnings she makes from weaving. It is an art that has not just been Chandra Kala’s source of livelihood, but also her way of life. She has handwoven most of the clothes in her family's home.

“Since learning to weave, I only own a few clothes that I didn’t make,” she says. “Why would I buy from others if I have the skills to make clothes with my own hands?”