Young people taking a selfie. Image by Iwaria, February 2021, free to use

Last year’s #EndSARS protests against police brutality, this year’s banning of Twitter and the #June12 protests across the country marking the historical battle to uphold democracy by resisting military dictatorship, are evidence of social media’s rising profile in Nigeria’s democratic landscape. For many Nigerians, social media has morphed into the tool of choice in outing the excesses of rich oligarchs and business people, promoting and mobilizing protests, and holding the government accountable.

This power of social media has rattled the Nigerian government. This explains why this free space is currently under assault, with freedom of expression and information dissemination as its latest victim.

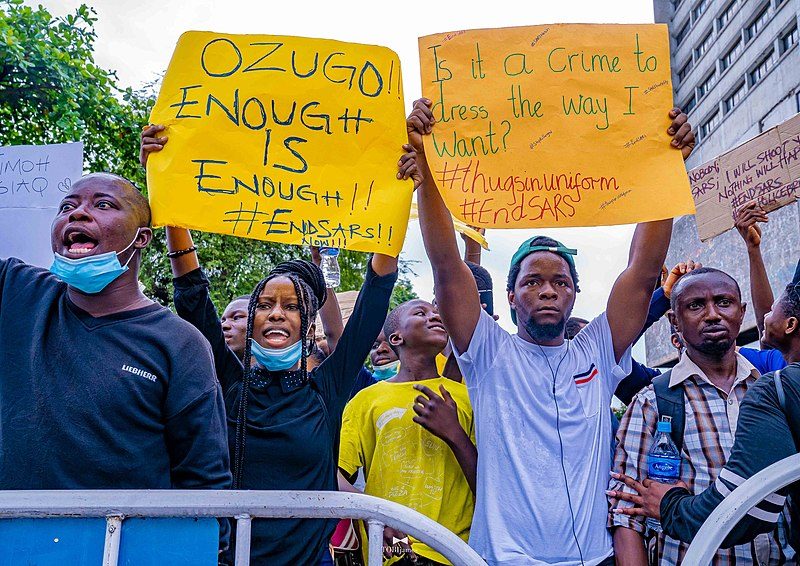

#EndSARS, the protest to end police brutality in Nigeria

The story of the Nigerian #EndSARS protests that finally reached its peak last year have been repeated over and over again — by activists, journalists, writers, filmmakers, and opinion writers. But they still bear repeating because it is at the root of the current assault on freedom of expression in Nigeria.

Agitations for the immediate disbandment of Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS)— the unit of the Nigerian police created in 1992 and notorious for illegal arrests, detentions, extrajudicial killings, sexual harassment of women, and brutalisation of young Nigerians — kicked off in 2017 as a Twitter campaign. Year in, year out, these agitations have always been met with the same promises to either reform or reorganize the group. But nothing happened.

By October 2020, Nigerians had had enough.

A tweet about a young man allegedly shot dead by the elite police unit, which has now garnered over 10,000 retweets since it was posted on October 3, was the first thing that grabbed people’s attention.

SARS just shot a young boy dead at Ughelli, Delta state as we speak. In front of Wetland hotels. They left him for dead on the road side and drove away with the deceased Lexus jeep.

I have videos…

— Chinyelugo (@AfricaOfficial2) October 3, 2020

The said video, one minute and 15 seconds long, came about four hours later, and from a different Twitter handle.

In the barely steady video, men are running towards what ended up to be a dead man dressed in a yellow pullover. The man had, allegedly, been killed by SARS officers.

This triggered Nigerians who immediately took to social media to express their infuriation, reviving the three-year-old hashtag — #EndSARS. This time, they wanted the police unit disbanded completely.

Hashtags — #EndSARS #EndPoliceBrutality — began to trend on Twitter. Infographics spread quickly on Instagram. Content creators got to work, journalists began to write, and activists began to galvanize people across the country.

The model for #EndSARS, unlike previous protests against the government, was not centred around any one individual, group, or organisation. Any one from any part of the country chose a location and a time and shared it online, and in a matter of minutes, people from that location began to gather in small groups in preparation for the protest.

“You messed with the wrong generation,” many young Nigerians wrote on Twitter. And they were ready to prove it.

In a few days, Nigerians both in Nigeria and in the diaspora were all on the street with one voice and campaigning for one cause — an end to SARS.

READ MORE: Global Voices Special Coverage — #EndSARS: A youth movement to end police brutality in Nigeria

In this period, Nigerians created a formidable team on Twitter — a decentralized fundraising effort, a team of volunteer legal professionals, volunteer cooks, private security officials, private medical officials, and netizens whose responsibility was to constantly tweet with the hashtag.

People reported arrested colleagues on Twitter and found solutions, people reported instances of police brutality and got medical support, people posted alerts of where SARS officials were operating and saved hundreds of other Nigerians from going that route, people gathered evidence (against the government and the police) in cases of extrajudicial killings.

The protests died down about a week after they kicked off, but not without leaving young Nigerians with very important lessons. Nigerians had finally recognised, in that moment, that Twitter was not just a social media platform. It’s where they can galvanize themselves to take action against the government, hold their government accountable, and build processes to circumvent their government’s inefficiencies. The Nigerian government was taking notes too.

The Twitter ban

On June 4, the Nigerian government banned Twitter. This, however, was not an isolated action.

The Nigerian government was following precedents set by governments within the continent — Egypt, Uganda, Ghana, Ethiopia — and others around the world — Iran, North Korea, and China. These governments have previously shut down or throttled the internet and blacked out social media while cracking down on all forms of communication among citizens.

In an almost unexpected twist of fate to the government, hours after the ban was announced, Nigerians found a solution. The day after the ban, June 5, Google Trends recorded an over 500% spike in searches related to VPNs in Nigeria.

The #June12 protests

June 12 holds a very strong and far-reaching symbolism for Nigerians.

On June 12, 1993, Nigeria held the first democratic presidential elections since the military coup of 1983. Nigerians came out en masse, defying bad weather, religious, class, and ethnic affiliations for an election that was described as the freest and fairest election in the country. Chief Moshood Kashimawo Olawale (MKO) Abiola, a Nigerian businessman and candidate of the now defunct Social Democratic Party, had supposedly won the election.

But the joy of June 12 was short-lived. The military government led by General Ibrahim Babangida annulled the results of the elections, citing election irregularities. This led to a political crisis. On June 11, 1994, Abiola announced himself as the lawful president of Nigeria. Abiola was detained for four years in solitary confinement, and in 1998, he died of unknown circumstances.

In 2018, the government in a bid to co-opt the symbolism of June 12, moved the Democracy Day celebrations from its initial date — May 29 — to June 12. Prior to 2018, June 12 was only celebrated in Lagos, the economic capital, and in some states in southwestern Nigeria.

As the 2021 Democracy Day drew near, agitations for a #June12 protest increased. The clampdown on Twitter precipitated a traumatic déjà vu for Nigerians old enough to remember the events surrounding Abiola’s incarceration and death.

So on June 12, damning all consequences and warnings from security operatives around the country, young Nigerians came out — again — to protest. This time, unlike the #EndSARS protests, Twitter had been banned. But people defied the ban by using VPNs to tweet.

The ripple effect of the use of VPNs was an avalanche of tweets in support of the #June12 protests in different countries of the world with little or no input from celebrities in those countries. With VPNs, Nigerians were able to get their tweets on global trending tables in many countries around the world — the U.S., the UK, Netherlands, Ukraine, Switzerland, Austria, and Belgium — garnering global attention to their cause from the protest grounds (or the comfort of their homes).

Nigerians are not letting go without a fight

#EndSARS protesters hold up their placards in front of the Lagos State House, October 11, 2020. Image by TobiJamesCandids via Wikimedia Commons

The Nigerian government had, once again, underestimated the resilience of its booming youth population, about 13.9 million of whom are unemployed. What appeared to be a strategic move on the part of the government intended to silence the voices of millions of Nigerians became yet another opportunity for Nigerians to mobilize. In the face of a defiant Nigerian Army, in the face of intense resistance, in the face of the possibility of being killed, many Nigerians took an opportunity to — once again — demand justice from the government.

For the average Nigerian, social media has morphed from being “just Twitter” or “just Instagram” — photo sharing apps and microblogging platforms. They have become avenues for Nigerians to create their own platforms without the risk of censorship, to galvanize themselves en masse for the purpose of securing their rights, and to expose the ills of their government. It’s not ‘just Twitter’; it’s the only platform Nigerians can ensure that their voices are not silenced and that they can hold an oppressive government accountable. It’s not ‘just Instagram’; it’s the only way we can preserve evidence of a mass shooting by the Nigerian Army.

Twitter is the only surviving bastion for political discourse in Nigeria. It’s a space for tech savvy, bold, and borderless young people constantly demanding good governance. It’s an independent channel for public information, exchange of news and ideas, outside the government’s regulation.

The Nigerian government knows this.

Nigerians were not letting go of the one thing that finally gave them a voice, a platform and an opportunity to hold their government accountable, without a fight.