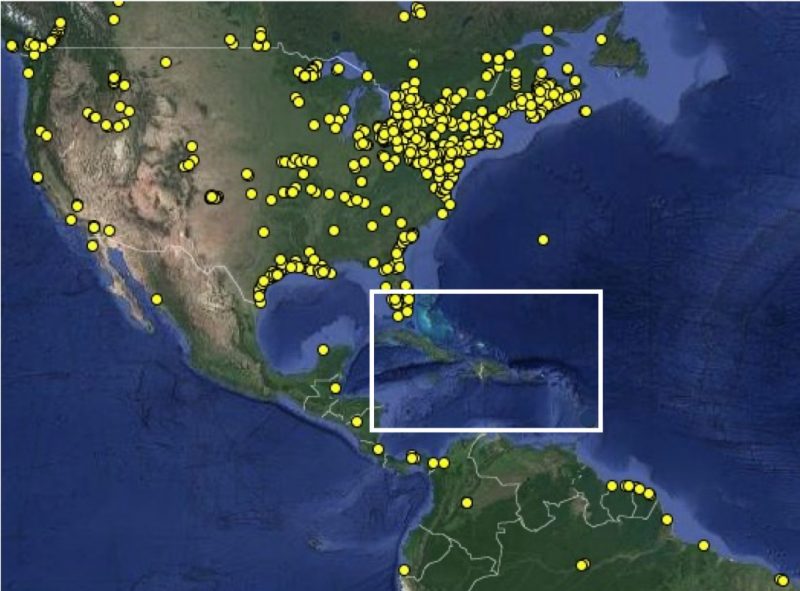

Graphic for the Caribbean Motus Collaboration, courtesy BirdsCaribbean, used with permission. Motus receiving stations function similarly to automated toll booths on a highway; every time a bird passes over the station, it’s recorded, just as automated toll booths record license plates. The stations have a range of about nine miles (15 km). Photo of the Ruddy Turnstone by Maikel Cañizares.

Across the Caribbean, thousands of birds of all sizes and species are busy preparing for their long journey to return to their northern breeding grounds. It’s migration time, marked by the celebration of World Migratory Bird Day [1], an event created by the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center [2] in 1993. It has been observed ever since by North American bird lovers each May, while birders in the Caribbean, Central and South America celebrate in October.

One of the questions on conservationists’ minds is how to determine which of the approximately 200 migratory species are on the wing at a particular time? Where might they be heading? Is their journey hundreds or thousands of miles? Where do they stop for rest and food? Now, an innovative programme could help shed some light on bird migration [3].

Designed with the objective of enabling conservation and ecological research by tracking the movement of animals, the Motus Wildlife Tracking System [4] is a powerful collaborative research network developed by Birds Canada [5]. Named after the Latin word for movement, Motus uses automated radio telemetry [6] to study the movements and behaviour of flying creatures, such as birds, bats and insects, that are nano-tagged and tracked by Motus receivers.

A Kirtland’s Warbler fitted with a lightweight nanotag. These tiny transmitters, which weigh as little as 0.2 g, allow researchers to track the movements of small animals with precision across thousands of miles. Photo by Scott Weidensaul, courtesy BirdsCaribbean, used with permission.

The system consists of hundreds of receiver stations and thousands of deployed nanotags on over 236 species, mostly birds. Scientists’ understanding of birds has already expanded because of data from this network, including pinpointing migration routes and key stopover sites, as well as movements, habitat use, and rituals during breeding and non-breeding seasons. This new technology and growing network of partnerships and data sharing hold great potential in bird and animal conservation.

The technology is also a valuable educational tool [7] with the power to advance conservation education, both in and out of the classroom. Birds Canada and the Northeast Motus Collaboration [8] have developed a curriculum that combines interactive classroom activities with Motus tracking tools, which can be used to teach local children about birds, migration, and conservation.

Although Motus is a widely established platform in Canada and the United States and is beginning to spread throughout Central and South America, there are currently no active receiver stations in the Caribbean. The greater the number of established Motus stations, the greater the understanding of where tagged birds are moving. In addition, many endangered and vulnerable species that either live in or migrate to the region have not yet been tagged.

It is a critical geographical gap that BirdsCaribbean [9], a regional non-governmental organisation, is keen to fill. It will be spearheading the Caribbean Motus Collaboration (CMC) in an effort to expand the Motus network regionally. The plan is to install and maintain receiver stations in strategic locations throughout the islands, deploy nanotags on priority bird species, and implement a specially adapted Caribbean educational curriculum.

The insular Caribbean is a global biodiversity “hotspot,” [10] home to over 700 species of birds. Roughly half of these are regional residents, including 171 that are endemic to the Caribbean. The other half are migratory, splitting their time between temperate and tropical habitats in the Americas, and making appearances in multiple countries along the way [11].

On this Motus receiver station map, the yellow dots represent active stations, while the white box outlines the parameters of the insular Caribbean. A few Motus stations that were put up in several islands have been damaged by storms and hurricanes, and need repair. Image courtesy BirdsCaribbean, used with permission.

For some migratory birds, the Caribbean is the perfect winter retreat—they arrive in early fall and stay until spring. Others use one or more islands as stopover sites to rest and refuel as they fly between their breeding and wintering grounds further south. Whether they stay or move on, they are much-loved visitors, reflecting the passage of the seasons and inspiring the region's cultural expressions, from folklore [12] to music [13].

However, bird populations are declining: 59 Caribbean species are at risk of extinction, with 30 listed as vulnerable, 24 endangered and five critically endangered, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature [14]. A recent study found that nearly 30 per cent of the bird populations in North America since 1970 have been lost, and Caribbean species are among the many that are in trouble.

Caribbean birds face an entire suite of threats, including habitat loss [15] and fragmentation, pollution, and invasive species. In addition, the climate crisis [16] has become a constant danger to the region, not just to people, but also to wildlife, with the region experiencing [17] increasingly intense hurricanes [18], long droughts and dramatic changes [19] to the marine environment.

While research on Caribbean birds has progressed considerably in recent decades, there is still a lack of basic information on many species. Knowledge gained from Motus collaborations is essential to safeguarding birds throughout their full life cycles and reversing population declines.

Caribbean natural resource managers and environmental organisations will use information from the Motus network to identify the key places where the region's resident and migratory birds live. Once identified, those in the Caribbean network and beyond will be able to focus their work on these areas, alleviating threats and protecting these sites.

The initiative will also contribute to the development of local research and environmental education programmes, through which it is hoped that local knowledge and appreciation for birds will multiply, a win-win situation for both the birds and those who work to conserve them in the region.

It is a hope that was buoyed by a recent announcement from the Joe Biden administration that it will revoke [20] a highly controversial rule initiated by former U.S. President Donald Trump to weaken the Migratory Bird Treaty Act [21]. The Act had protected birds since 1918, making it illegal to pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect migratory birds, their eggs or nests—or attempt to do so, without a permit. Although the contentious rule went into effect on March 8, it will shortly be replaced by new guidelines. Ornithologists and wildlife advocates across the Americas are counting this development as a major win.

It is unclear at the moment which Caribbean island will be the first to establish a receiving station to track the movements of its fragile bird populations on their south-north round trips, but the hope is that the programme will spread quickly and densely throughout the archipelago.