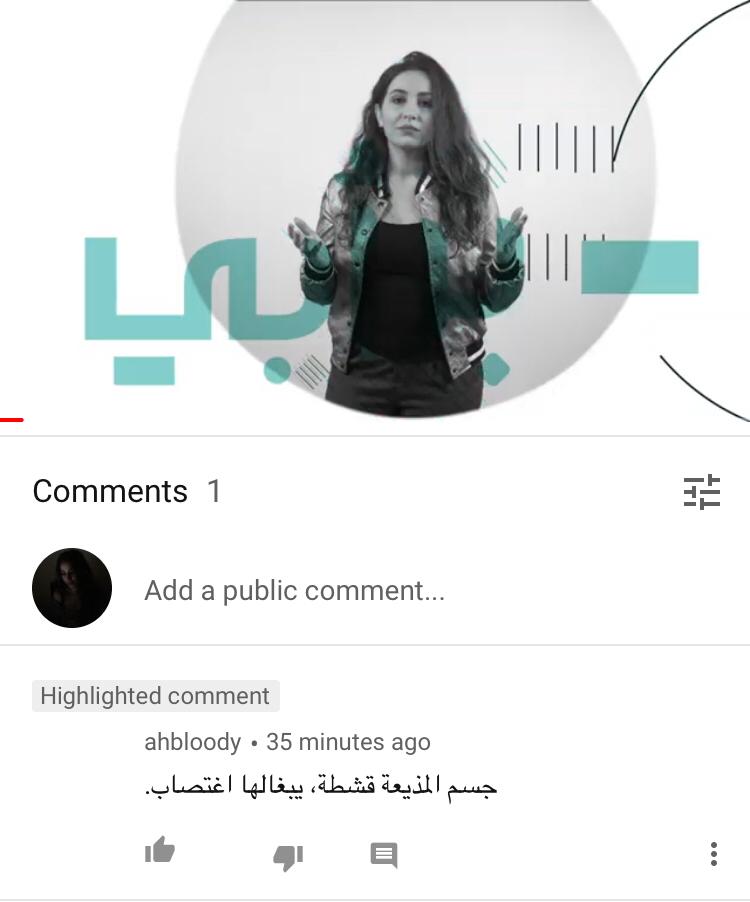

A viewer of a video presented by journalist Maya El Ammar left a comment that read: “The presenter’s body is like a sweet shop and is worth a rape”.

Women journalists, feminists, activists, and human rights defenders around the world are facing virtual harassment. In this series, global civil society alliance CIVICUS highlights the gendered nature of virtual harassment through the stories of women working to defend our democratic freedoms. These testimonies are published here through a partnership between CIVICUS and Global Voices.

Since October 2019, anti-government protests known as the “October Revolution” have erupted across Lebanon. Protesters have called for the removal of the government and raised concerns about corruption, poor public services and a lack of trust in the ruling class. Protests have been met with unprecedented violence from security forces. The country has faced an ongoing political crisis, which was worsened by the Beirut port explosion in August 2020. Feminists have been at the forefront of the revolution and have stepped up to provide assistance in the aftermath of the explosion. Since the revolution began, the government has intensified its crackdown on free speech, and journalists have also faced attacks.

Maya El Ammar is a feminist writer, activist and communications professional who currently contributes to various media outlets as a journalist, writer and translator, produces her own opinion videos covering a range of feminist and human rights issues and publishes gender-focused articles in collaboration with independent media platforms alongside her job as a media strategist for a non-profit organization. She has a BA in journalism and an MA in communication studies.

This is Maya El Ammar's testimony:

Speak up, woman! But to whom?

“The presenter’s body is like a sweet shop and is worth a rape,” was one man’s reaction to a 2018 video I produced, not on sugar-apples, but on the bias of Lebanese media in covering femicide cases.

“If that’s what you wear for work … I wonder what your nightgown looks like?”

“Why don’t you eat a ‘banana’?” and,

“Why should I hear from an impure woman such as yourself?” wondered others.

That was in response to my piece in the same year on the kafala (guardianship) slavery-like conditions enforced on domestic workers and their similarities with marriage laws in our region.

A year later, things escalated to, “Reply to my email and answer my calls or else I’ll have to come to your office, Maya.” That was the first time in my life I consulted a lawyer, for this very polite threat was the culmination of a sickening combination of online and offline stalking, delusions, lies, and what I call a man's “revenge thorn” after I pursued a story—my story—without him.

In my case, it was a male videographer and civil society worker I crossed paths with. He has even gone so far as to start harassing the person at the center of the story, in order to punish me. But luckily, I survived that, too. I even told myself what I would never tell my friends or say out loud, that this was still considerably trivial in comparison to the more serious violations my colleagues, and women in general, face. The “It’s not daily threats or rape yet” melody kept me going because there was so much I wanted to do that I did not wish to be stopped, let alone to publicly share.

The strange revelation that has just hit me is that thousands of other women are having to deal with similar violations as I write this, and as you read it.

Many of them are probably dealing with their ordeal with an odd level of acceptance. And I say this because, as women, I suppose we have always seen those misogynist and ad-hominem commentaries hovering over our heads, coming to land in the digital spaces we decided to claim, just as we once decided to claim public spaces. History does repeat itself sometimes.

Thanks to our own experiences with gender-based violence in the offline world, we have rationalized the reality that our virtual world would only naturally mirror our off-screen existence. Thanks to the women whose inspiring trajectories have often had to be turned into outright warnings for their successors, we have perhaps unintentionally come to terms with the inevitability of going about our lives being victimized. It turns out that as girls we all had to be born prepared, though unarmed. And the worst part of it all is realizing decades later that as women, we still are unarmed, underequipped and uncared for. So we might as well care less for ourselves and our own wellbeing, might we not?

As women journalists and activists from the Middle East and North Africa, our force is a destabilizer, but also a parasite, a thing to deal with later when the ever more important issues are dealt with. And as independent women journalists and activists, we are all the more unprotected and unendorsed by any higher establishment.

“Hope for the best but always expect the worst,” my sister used to tell me.

I don’t think she realizes that I ended up expecting the worst, incessantly. Instead of chasing hope, I opted for being on alert for the worst. At the time, maybe I thought this could help me grow into Destiny Child’s “strong, independent woman.” But a few years later I found out that it actually meant I had to coexist with my fears, and accept this open relationship with the leftovers from my Freeze-or-Flee-or-Fight skills. In digital terms, these would be the Ignore-or-Block-or-Report skills.

But report to whom? To giant tech corporations that couldn’t care less about our safety, so they prioritize removing language that bothers authoritarian and “apartheid” regimes in the region over addressing reports of sexist and harmful content? Or to companies that are much quicker to disapprove “sensitive ads” and censor political Arabic content than they are to respond to threats of violence, bullying and harassment?

Report to whom? To national cybercrime bureaus that may have proved effective in tracking and arresting perpetrators of blackmailing and sextortion, and yet remained way more effective in unlawfully prosecuting social media users and arresting journalists, including women, for expressing unwelcome opinion?

As I write these lines, I cannot but think of my female colleagues who are constantly pushed to deal with the shadow of a monstrous police-state apparatus compounded by outpourings of attacks against “who they are,” but rarely against “what they say.”

Miraculously, these same women refuse to back down and are becoming even more determined to point the finger at the corrupt and the harasser, and dig for answers on who killed their colleagues, the researchers, the thinkers, the journalists, and on who was behind the improperly stored 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate that destroyed half of Beirut.

If the recently approved anti-harassment law was passed in Lebanon for a reason, it should be for them, and for the 307 per cent rise in official reports of online violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. This new—albeit weak—law should be for all the women whose work is never enough and are often expected to sacrifice more, yet are the first to be sacrificed during crises.

This new law, which encompasses online harassment and could see the most flagrant perpetrators spend up to four years in prison, should be for all the brave women who are taking individual and collective action to protect themselves and their communities. Most importantly, it should be for those among us who are still reluctant to seek help for fear of retaliation, and lack of trust and hope.