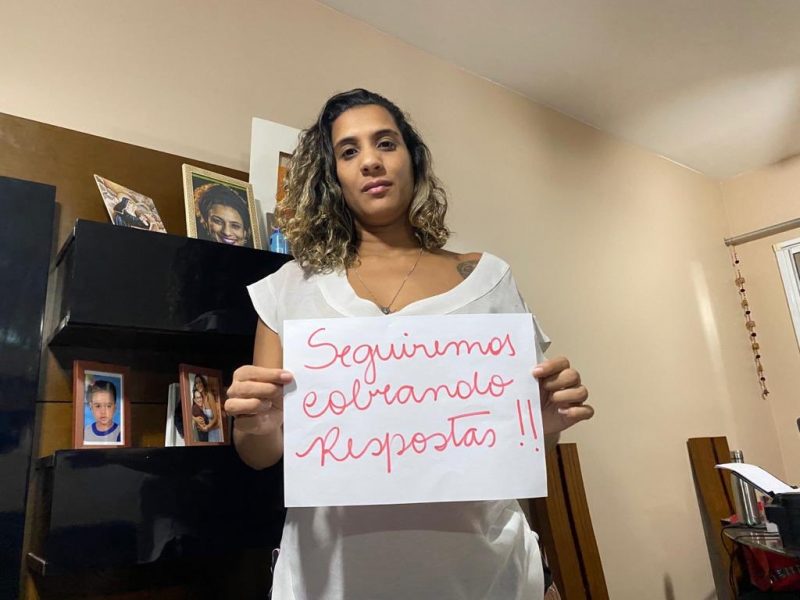

Anielle Franco, Marielle's sister. Message: We will continue demanding answers. Photo: Reproduction/Instituto Marielle Franco. Used with permission.

On May 27, Brazil's High Court of Justice (STJ) ruled that the investigation of the murder of Marielle Franco, the Rio de Janeiro city councillor killed in March 2018 [1], would remain in the hands of the state police and not be handed over to the federal authorities.

Marielle's family members and advocates have feared that moving the case to federal level would make it vulnerable to interference by President Jair Bolsonaro, whose family has links with the suspects [2] in the crime.

Marielle was a black, bisexual, favela-born elected city councillor in Rio de Janeiro for the Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL). On the night of March 14, 2018, the car she was in on her way home was shot 13 times [3], killing her and her driver Anderson Gomes. Marielle was 38, and Anderson was 39.

Investigation of the murders has been handled by Rio de Janeiro's Civil Police and the State Public Prosecutor's Office since. However, in late 2019, the Attorney General's Office requested [4] Brazil's Federal Police, which is subordinate to the Ministry of Justice, to take over the probe.

The attorney general at that time, Raquel Dodge, alleged that the investigations were likely compromised inside the state sphere given the delay in finding the assailants.

Marielle and Anderson's families immediately opposed the request. The Marielle Franco Institute launched the campaign [5] “Federalização Não!” (“No Federalization!”) and collected 150,000 signatures of support, including from 200 civil society organizations.

The families also sent an open letter to the STJ's justices, which stated [6]:

Muitas são as razões fáticas e jurídicas que nos levam a acreditar que a federalização do caso não é o caminho que as instituições de Justiça devam seguir para garantir a responsabilização de todos os envolvidos no bárbaro crime que tirou a vida de nossos familiares. (…) Ao contrário do alegado pela PGR (Procuradoria Geral da República), a federalização do caso revela-se justamente como a abertura do caminho para a impunidade dos responsáveis pela prática dos crimes.

There are many factual and legal reasons that lead us to believe that federalizing the case is not the path that the institutions of Justice should follow to ensure accountability of all those involved in the barbaric crime that took the lives of our relatives. (…) Contrary to what the PGR [Brazil's Attorney General's Office] claims, the federalization of the case shows itself to be precisely the beginning of the path to impunity for those responsible for committing the crimes.

The STJ eventually denied the federalization of the case. The Institute Marielle Franco celebrated the decision on Twitter:

VITÓRIA! Por 5×0 no STJ a federalização do caso Marielle e Anderson já está NEGADA! Foram mais de 150 mil pessoas e mais de 200 organizações da sociedade civil assinando contra a federalização, e inundamos as redes com a hashtag #FederalizaçãoNão [7]

Não temos como agradecer o apoio! pic.twitter.com/A4bzeAks1I [8]— Instituto Marielle Franco (@inst_marielle) May 27, 2020 [9]

VICTORY! By 5 to 0 in the STJ the federalization of the Marielle and Anderson case was DENIED! Over 150,000 people and over 200 civil society organizations signed against the federalization, and we flooded social media with the hashtag #NoFederalization

We can't thank you enough for your support!

Anielle, the institute's president, spoke with Global Voices on WhatsApp in June. She said:

Foi uma vitória não só para a família, mas para todos os 154 mil companheiros e companheiras que assinaram essa mobilização da sociedade civil contra a federalização. (…) Essa votação foi unânime e importante no meio de tanto caos, de tanta interferência e de tanta dor.

It was a victory not only for the family, but for all the 154,000 comrades who signed [to support] this mobilization by civil society against the federalization. (…) This vote was unanimous and important amid such chaos, such interference and such pain.

Anielle added:

Esperamos que as investigações evoluam, finalmente. Esperamos não ter que esperar mais dois anos para descobrir quem mandou matar minha irmã. Quem sabe um dia teremos esse caso solucionado.

We hope that the investigations will progress finally. We hope we don't have to wait another two years to find out who ordered my sister's murder. Maybe one day we'll have this case solved.

The Bolsonaro family connection

In the year following Marielle and Anderson's murders, investigations made little progress. Between March and August, police discovered links between the killers and a group of militia [10] members known as the “crime [11]bureau [11]“; in Rio de Janeiro, what is commonly called “militias” are paramilitary groups comprised of off-duty police officers linked to organized crime.

In January 2019, an operation by the Prosecutor's Office found that President Jair Bolsonaro's son, Senator Flavio Bolsonaro, employed [12] in his office the mother and the wife of one of the “crime bureau” leaders, the former police officer Adriano da Nóbrega.

In March, two other names associated with the “bureau”, Ronnie Lessa and Élcio Vieira de Queiroz, were arrested [13] for the murders. According to the police, Lessa shot Marielle while the former police officer Queiroz drove the car that pursued the councillor's vehicle. Authorities still don't know who ordered the murder.

Ronnie Lessa lived [14] in the same residence compound [15] as President Jair Bolsonaro, in a wealthy area of Rio de Janeiro. A doorman initially told the police that Queiroz was allowed to enter the compound on March 14, 2018, hours before the murders, by somebody in the house belonging to Jair Bolsonaro, who at that time was a federal deputy.

Days later, the doorman changed [16] his version of events to the police, declaring in a statement that he had mistaken the number of the house.

Bolsonaro then accused [17] Rio de Janeiro’s governor, Wilson Witzel, of manipulating the investigation to try to destroy his reputation. Witzel denied the accusations and said he would sue Bolsonaro for them.

Further controversies

Before the High Court of Justice's decision, Bolsonaro exchanged messages [18] with the then Justice Minister Sergio Moro saying that he wanted more control over the Superintendence of Rio de Janeiro’s Federal Police. In a meeting with his ministers on April 22, the Brazilian president was filmed [19] saying:

Já tentei trocar gente da segurança nossa no Rio de Janeiro, oficialmente, e não consegui! E isso acabou. Eu não vou esperar foder a minha família toda, de sacanagem, ou amigos meu [sic], porque eu não posso trocar alguém da segurança na ponta da linha que pertence à estrutura nossa. Vai trocar! Se não puder trocar, troca o chefe dele! Não pode trocar o chefe dele? Troca o ministro! E ponto final!

I've already tried to change our security people in Rio de Janeiro, officially, and I didn't manage it! And that's over. I won't wait to get my whole family screwed, by dirty tricks, or friends of mine, because I can't change somebody from the security at the end of the line belonging to our own system. They will be replaced! If you can't change them, change their boss! You can't change their boss? Change the minister! And that's it!

Moro resigned [20] from the government shortly thereafter. He said that what triggered his resignation was Bolsonaro's demand [21] to sack the director-general of the Federal Police, Marcelo Valeixo, a Moro ally.

After Moro resigned, the president replaced Valeixo with Alexandre Ramagem [22], but the appointment was soon afterwards blocked by Brazil's Supreme Court. Justice Alexandre de Moraes found that Ramagem had too many personal ties to the president's family — photos [23] of him with Bolsonaro's sons on New Year's Eve had been shared on social media. Bolsonaro then nominated somebody linked to Ramagem, Rolando [24] Alexandre de Souza.

One of the first things Souza did in his new role was to replace [25] the superintendent of Rio de Janeiro's Federal Police.

Regarding the federalization of the Marielle case, the Attorney General's Office can still appeal the decision of the High Court of Justice to the Federal Supreme Court, the highest court in Brazil.