Shumona Sinha. Photo by Francesca Mantovani/Gallimard, used with permission

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union and India enjoyed a particularly friendly relationship as they shared ideological common ground. Tsarist Russia had long supported anti-British movements, having its own colonial ambitions in the region. After 1917, the Soviet Union increased its presence in India through Communist ideology, and according to one interpretation, the Communist Party of India (CPI) was actually established in Tashkent in 1920.

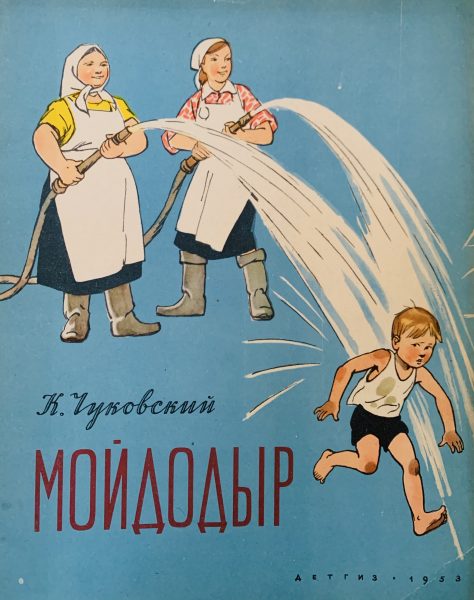

Cover of a 1953 edition of the iconic children story Moydodyr by Korney Chukovsky, which was first published by Lev Klyachko in the 1920s in his Raduga publishing house. Photo by Filip Noubel, used with permission.

Up until its demise in 1991, the Soviet Union supported the translation, and distribution of Russian and Soviet literature that influenced generations of Indian children and intellectuals.

This Russia-India relationship is the central plot of Shumona Sinha latest book, “Le Testament Russe” (The Russian Will).

Like many of her peers, Sinha grew up in Kolkata reading those same novels. She eventually moved to France, and became an acclaimed exophonic writer — or a writer that produces work in their non-native language.

“Le Testament Russe” centers around Tania, a young Bengali girl living in 1980s Kolkata. The heroine escapes her social and family background by joining the local Communist student movement, and eventually studying Russian. But her real inspiration is Lev Klyachko, the Jewish-Russian journalist who decided to become a publisher in the 20s, launched the politically independent publishing house Raduga, worked with the luminaries of Russian literature and art such as Korney Chukovsky, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin but was eventually censored and died in 1933.

GV author Filip Noubel interviewed Shumona Sinha to find out more about how Soviet children books shaped her own journey through languages, cultures and identities. The interview was edited for brevity.

Filip Noubel (FN): In your latest novel, you explore the ties – some of them going back to the 18th century – that have linked Russia and the Soviet Union to Bengal through ideology and children books in translation. Could you tell us more about this heritage? Was it also your experience when you grew up in Kolkata?

Shumona Sinha (SS) L’héritage de la littérature russe au Bengale occidental crée le cadre de mon roman, oui. Beaucoup de Bengalis qui possèdent une collection de livres chez eux, ont un rayon russe. Les livres russes et soviétiques ont joué un rôle important et pourtant délicat, ont influencé les pensées de tant de Bengalis, façonné leur regard sur la vie. Non seulement les classiques mais aussi les auteurs de la jeunesse comme Nicolaï Ostrovski, Arkadi Gaïdar, Dmitri Mamine Sibiriak, Boris Polevoï… C’était pareil chez moi. D’autant que mon père était économiste, professeur d’économie à l’institut équivalent de Science-Po, marxiste et leader communiste des années 1970. Il a failli être assassiné par les hommes de main d’Indira Gandhi. C’est d’ailleurs le sujet de mon troisième roman Calcutta. J’ai grandi avec les livres russes. Mes premiers contes de fées étaient russes, et non bengalis. C’est pourquoi j’ai été éprise de Kliatchko ! En fouillant dans les archives on trouve sa trace, mais rien n’a été écrit sur lui depuis sa mort, personne n’a contacté sa famille. Trouver leur trace et raconter cette histoire était une noyade voluptueuse pour moi.

Shumona Sinha (SS) Indeed the frame of my book is created by the heritage of Russian literature in West Bengal. Many Bengalis who own books have a shelf of Russian books. Russian and Soviet books played a key and delicate role, and have influenced the thinking of so many Bengalis, shaped their take on life. Not just the classics, but also authors of children literature, such as Nikolay Ostrovsky, Arkady Gaydar, Dmitri Mamin-Sibiryak, Boris Polevoy…It was the same in my home. Besides, my father was an economist, teaching that subject, and a Marxist as well as a Communist leader in the 1970s. He almost got killed by Indira Gandhi's henchmen. This is actually the topic of my third novel called “Calcutta”. I grew up with Russian books. My first fairy tales were Russian, and not Bengali. This is why I fell in love with Klyachko! By digging in archives, one can find his trail, but nothing has been written about him since his death, no one contacted his family. To find them and to tell that story gave me a voluptuous feeling of drowning.

FN: Your novel is also a book about books. Tania, whose father owns a bookstore that sells Soviet books, but also Hitler’s Mein Kampf, is fascinated by the fate of the publisher Lev Klyachko. What is the power of books and literature today?

SS: La scène d’autodafé de mon roman est imaginaire. La vente libre de Mein Kampf, le fait qu’il soit un best-seller en Inde, surtout parmi les jeunes, m’ont révoltée. Depuis la montée au pouvoir national de Modi alias son parti suprémaciste hindouiste BJP, depuis les déclarations massives et éhontées pro-Hitler, islamophobes de ses électeurs, j’ai voulu en parler dans mon roman. Le pouvoir des livres et de la littérature est majeur. Mais les livres aussi mentent, ce n’est pas mentir-vrai comme a dit Aragon, mais plus compliqué. On propage les idées suprémacistes, sectaires, religieuses, en guise d’une quête personnelle spirituelle. Doit-on bannir ces livres-là ? C’est le piège de la démocratie. Le capitalisme est un totalitarisme à ciel ouvert. On me considère comme un écrivain engagé, mais dans mes livres je cherche à explorer les complexités de la vie, j’ai horreur des discours binaires, dogmatiques. La littérature n’a pas la prétention de changer le monde, mais elle peut dévoiler la condition humaine, elle peut semer les germes d’espoir, de rêve pour un monde meilleur, accompagner le lecteur esseulé et lui donner un élan renouvelé.

SS: I imagined the scene in my novel where books are burnt. The fact that “Mein Kampf” is readily available, that it is a best-seller particularly among young people in India revolted me. Since Modi gained power together with his Hindu supremacy party the BJP, massive and shameless statements have been made by his voters in favor of Hitler and against Muslims. I wanted to talk about this in my novel. The power of books and literature is huge. But books also lie. French poet Aragon once created a neologism: “mentir-vrai” meaning that books lie to say the truth, but it is in fact more complicated than that. People spread ideas of supremacy, sects, religion pretending this is all a personal spiritual quest. Should such books be banned? This is the trap of democracy. Capitalism is an open air form of totalitarianism. People describe me as a writer who is “engagé” – who is politically and socially involved, but in my books, I try to explore the complexities of life. I hate binary and dogmatic discourse. Literature does not pretend it can change the world, but it can unveil the human condition, plant seeds of hope, of dreams of a better world, provide company to the lonely reader and give them a new impulse.

FN: Your novel spans across India and Russia – you also traveled many places, including the US to research the novel and the history of Klyachko. Do you accept the label of global novel for “Le Testament Russe”? Is all literature global in the 21st century?

SS: Bien sûr, je le prends comme un compliment. C’est même l’aspiration du Testament russe.Même si tous les romans du XXIème siècle ne le sont pas. Il y a des romans français qui s’inscrivent dans le contexte historico-social franco-français. Ce n’est ni une qualité de plus, ni un défaut évidemment.

SS: Of course, I take that word as a compliment. This is what my novel aspires to. But not all novels of the 21st century are global, certain French novels remain grounded in a typically French historical and social context, which is not to say this is a quality or a fault, obviously.

FN: You are a global and exophonic writer. You have transitioned across cultures and languages – what has this process brought you? How have you negotiated your multiple identities? What are the challenges and advantages of writing in a non-native language?

SS: Je suis venue à la littérature non seulement pour franchir les frontières mais pour les voir effacées. Je n’ai jamais eu de solidarité ethnique ou communautaire. Je me considère comme une métisse culturelle, une nomade et heureuse de l’être. Ce n'est pas l’Inde ou la France qui sont ma patrie, mais la langue française.

Quant à écrire en français, on ne choisit pas la langue, c’est la langue qui nous choisit. Alors on n’a plus le choix. Ça se passe dans le corps. On est habité par la langue. Le français m’était d’abord une langue étrangère, ensuite une langue autre, puis la langue, ma langue. Toutes les autres langues natales de ma vie antérieure sont endormies, comme des rivières souterraines, elles ne sont pas manifestes, et le français est devenue ma langue vitale car je ne sais plus concevoir ma vie dans une autre langue que le français. Écrire en français est révolutionnaire pour moi qui ai écrit en bengali quand j’étais adolescente et jeune femme, et je n’ai jamais écrit en anglais. Contrairement au bengali qui est une langue limpide, le français est une langue rationnelle et analytique, ainsi écrire en français a façonné ma pensée. Les interrogations linguistiques et existentialistes sont devenues la matière de mes livres. Quand on est écrivain en situation d'exophonie, on vit toujours une intranquillité vis-à-vis de la langue autre. Cet état est excitant, propice à la création.

SS: I came to literature not only to cross boundaries, but to see them disappear. I never felt ethnic or communalist solidarity. I consider myself to be a person of mixed cultural origins, a happy nomad. My home country is not India or France, it is the French language.

Regarding the fact that I write in French, we don't get to choose the language, it is the language that chooses us. And then we no longer have a choice. This takes places inside the body. French was a foreign language for me, then it became another language, then the language, and finally my language. All the other mother tongues of my previous life have fallen asleep, like underground rivers, they are not visible, and French became a vital language because I can only conceive my life in that language. To write in French is revolutionary for me, as a person who used to write in Bengali when I was a teenager and a young woman. I never wrote in English. Unlike Bengali, that is a limpid language, French is rational and analytical, thus writing in French shaped my thinking. Linguistic and existentialist questions have become the inspiration for my books. When you are an exophonic writer, you are always in a relation of non-tranquility with the other language. This state of mind is exciting and conducive to creation.

FN: Your book is also a homage to translators, such as Nani Bhowmik. You have also worked as an interpreter for asylum seekers. How important are literary translators?

SS: Le travail des traducteurs littéraires est d’une valeur inestimable ! Ils jouent un rôle primordial pour construire les ponts et les passerelles entre les pays et les cultures. Nani Bhowmik est d’un talent rare. Il a écrit lui aussi des romans, primés par l’Académie indienne de la littérature. Son œuvre est marquée par son voyage entre deux langues, sa langue d’écriture est innovante, affranchie, fantasque et profonde. Pour ma part je me sens plus heureuse de mes anthologies de poésie française et bengalie contemporaines dont j’ai assuré la traduction. Les traducteurs qui ne sont pas eux-mêmes des écrivains, ils réécrivent les textes d’origine dans la langue d’arrivée. C’est à la fois une contribution linguistique, littéraire et socioculturelle. Les livres traduits qui franchissent les frontières sont les messagers d’espoir et de liberté.

SS: The work of literary translator has immense value! They play a key role to build bridges between countries and cultures. Nani Bhowmik was a man of rare talent. He also wrote novels awarded by the the Indian Academy of Literature. His writing is shaped by his journey between the two languages, Russian and Bengali, it is innovative, free, whimsical and deep. As for me, I am particularly happy with my anthologies of contemporary French and Bengali poetry which I translated. Translators who are not writers themselves rewrite texts produced in the source language in the target language. This represents a linguistic, literary and socio-cultural contribution. Translated books that cross borders are messengers of hope and freedom.