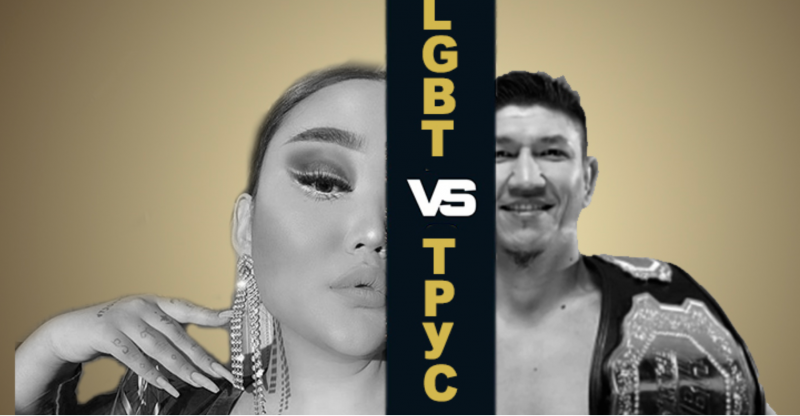

A photo collage from the Kazakhstani LGBT magazine Kok.team [1]. The Russian language text reads: “LGBT Versus Coward”. Image used with permission.

A row between a lesbian activist and a weight fighter has launched a fierce debate on Kazakhstan’s social media networks, revealing deep fractures about national identity among the youth of this Central Asian nation.

In mid May 2020, the Kazakh heavyweight fighter Kuvat Khamidov started uploading a series of tweets on his account calling for the killing and rape of members of the LGBTQ community, including posts such as:

почему есть отстрел бродячих собак, но нет отстрела педиков?

— Kuat Khamitov (@Kuat_Khamitov) May 22, 2020 [2]

Why are stray dogs shot, but not fags?

This caught the attention or Nurbibi Nurkadilova, an LGBTQI rights activist who responded to Khamitov on May 17, the International Day [3] against Homo-, Trans- and Biphobia. She wrote a long letter addressed to the fighter [4] on her Instagram account, which has so far received nearly 3,000 comments.

Part of her letter states:

Я являюсь открытым представителем ЛГБТ+ сообщества!

И своим заявлением, вы оскорбили меня, моих друзей и моего любимого человека! Что в вашем понимании, «такие люди хуже собак»? Вы сравниваете мои человеческие права, права гражданина этой страны, с собачьими – то есть, считаете меня бесправной? Своими высказываниями, вы откидываете страну назад! Вы препятствуете развитию!

I am a member of the LGBT+ community!

With your statements, you have insulted me, my friends and the person I love! What do you mean when you say that “those people are worse than dogs” [In reference to one of Khamitov's tweets, since deleted.] Are you comparing my human rights, my civic rights with those of dogs? Does that mean you consider me to have no rights? With your statements, you're taking this country backwards! You are an obstacle to progress!

Following her post, Nurkadilova says [5] she has received threats from sportsmen and wrestling fans:

В срочном порядке мне пришлось сменить место жительства, меня эвакуировали правозащитники. Я сменила квартиру, потому что ко мне домой начали заявляться незнакомые люди.

I had to urgently leave the place where I used to live, I was evacuated by human rights activists. I changed flats when unknown people started showing up at my door.

Clearly she has struck a nerve, which she mentions in her long post: the different – and conflicting directions young people in Kazakhstan would like their country to take.

The (re)invention of ‘traditional values’

In the ideological vacuum left after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, a number of post-Soviet states had to build alternative nation-making narratives. It was a challenging task: many former Soviet republics had only a very short prior history as modern nation-states, their intellectual elites had been wiped out in the Stalin-era purges of the 1930s, and the ethnic balance of power had been established by Soviet policies of privileging ethnic Slavs and Russian speakers. Kazakhstan was no exception.

The relative ideological leniency of the perestroika period of the mid-1980s allowed for the emergence of new discourses which had been severely suppressed in previous decades. The strongest of these new discourses concerned religion and national identity.

So when Kazakhstan became independent in 1991, the groundwork for an ethno-nationalist awakening had been laid for decades. Citizens sought to rekindle religious and conservative social norms and models which they could define as both non-Soviet and non-western. They advocated a return to an imagined and invented “traditional” model of patriarchy, heteronormativity, and strictly defined gender roles. It was a trend observed across the former Soviet Union, from Central Asia to the Caucasus and Russia itself.

In this understanding of Kazakh society, LGBTQ people were outsiders. Although the country decriminalised same-sex activities in 1998, there is still no legal protection [6] against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity; according to Human Rights Watch hate crimes against LGBTQ people are frequent [7]. Meanwhile, religious leaders of both the Islamic (about 70 percent of the population) and Orthodox Christian communities are known to support a strongly anti-LGBT discourse. [8]

But there are some young Kazakhstanis [9] who reject those values, such as Nurkadilova herself.

Global Voices asked the founders of Kok.team [10], a trilingual Kazakhstani LGBT online magazine founded by Daniyar Sabitov and Anatoly Chernoussov what the Nurkadilova versus Khamitov spat reveals about the worldview of Kazakhstan's youth:

Мы еще раз убедились, что в Казахстане существуют два лагеря людей, которые радикально противостоят друг другу, когда речь заходит о правах человека в контексте ЛГБТ. Их борьба очень важна, потому что ведется она на поле третьего лагеря – людей, которые пока не определились.

This once again confirms to us that there are two groups of people in Kazakhstan who stand in radical opposition to each other when discussing the human rights of the LGBT community. Their fight is important, because it takes place before third group — people who remain undecided.

Nevertheless, Sabitov and Chernoussov believe that this scandal is particularly unique:

То, что у Нурбиби большая стабильная лояльная аудитория подписчиков, которая только растет – вот это может быть индикатором того, что у части молодежи есть запрос на новых героев. Это первая ЛГБТ-активистка не из числа “купленных Америкой городских сумасшедших”, как думают о нас, а активистка с большим социальным капиталом.

The fact that [Nurkadilova] has a stable and loyal audience that keeps growing is perhaps an indicator that part of Kazakhstan's youth is seeking new role models. She is the first LGBTQ person who cannot be simply dismissed as one of the “urban crazies who are influenced and bought by the US,” as we are often described. She is an activist who has her own significant social capital.

Music versus stereotypes

In recent years, music has become an important means for Kazakhstan's youth to raise issues of identity and gender inequality. One band which has played an important role in that discussion is the wildly popular K-pop style boys band Ninety One [11]. The band sings almost exclusively in Kazakh and its public presentation shows its members’ interest in subverting gender stereotypes and identities. This video alone received five million views — not a trivial number given that Kazakhstan has a population of 18 million [12].

The fact that such a band could become cultural icons is highly significant in modern Kazakhstan. Yevgenia Plakhina, a Global Voices contributor and close observer of Kazakhstan's popular culture, co-produced a documentary [13] about Ninety One which seeks to expand the debate about role models for Kazakhstan's youth. She shared her thoughts with Global Voices about the band's importance to discussions on gender identity in Kazakhstan:

Группа Ninety One появилась, когда в Казахстане полным ходом шел процесс ре-традиционализации – перепридумывания традиционных ценностей. Почему они стали причиной ожесточенных дебатов? Во-первых, у них очень много фанатов по сравнению с другими казахскими группами – около 600 тысяч подписчиков на YouTube, около 575 тысяч подписчиков в Instagram. Во-вторых, они выглядят не так, как канонически должен выглядеть казахский мужчина – сережки в ушах, крашеные волосы, яркая одежда. В третьих, за это они очень нравятся девушкам и женщинам, уставшим от образа казахского мачо. В четвертых, против них сложно использовать риторику, что все зло приходит с Запада. K-Pop, который в Казахстане, превратился в Q-Pop пришел к нам с Востока. В пятых, ребята поют на казахском и собирают вокруг себя ту аудиторию, которую хотели подмять под себя традиционалисты.

The band Ninety One emerged when Kazakhstan was undergoing a “return to traditions”, or the reinvention of traditional values. Why did the band become the subject of so many debates? Firstly, because they have a large number of fans compared to others in Kazakhstan: around 600,000 subscribers on Youtube and 575,000 on Instagram. Secondly, they do not appear as traditional Kazakh men are supposed to: they wear earrings, dye their hair, and wear bright clothes. This is why many young girls and women love them;they are tired of the typical Kazakh macho man. Furthermore, one cannot use them to advance the narrative that all evil comes from western culture: K-pop [Korean pop] came from the East, and turned into Q-pop in our country [Kazakh is written Qazaq in Kazakh Latin script]. Finally, they sing in Kazakh and gather the audience that supporters of traditional values would like to influence the most.

Фанаты Ninety One открыты для новых идей и не хотят строить такое общество какое строили их предки 200 лет назад. Конец 1990-х в Казахстане,был временем относительной свободы. В мои студенческие годы популярной была MC Гуль [14] – женщина, читающая рэп (кто бы мог подумать!). В казахоязычной среде, я думаю, это была группа «Орда [15]». Именно оттуда вышел продюсер группы Ninety One – Ерболат Беделхан.

Ninety One fans are open to new ideas and do want to build a society inspired by their ancestors 200 years ago. In the late 1990s, Kazakhstan experienced relative freedom. When I was a student, the female rapper MC Gul [14] was popular. In Kazakh-speaking areas of the country, it was the band Orda [15], whose member Erbolat Bedelkhan became the producer of Ninety One.

It can even be argued that Ninety One has been more successful than Kazakhstan's government in promoting the use of the Kazakh language, by singing almost exclusively in Kazakh and promoting the new spelling of the language in the Latin alphabet. The following video, which already has over 200,000 views on YouTube, is a good example:

Perhaps the strongest message of Nurkadilova's letter was that Kazakh culture is not solely the property of nationalists and traditionalists —and that exploration and a thirst to explore new pastures is not a novelty for Central Asia's largest country.