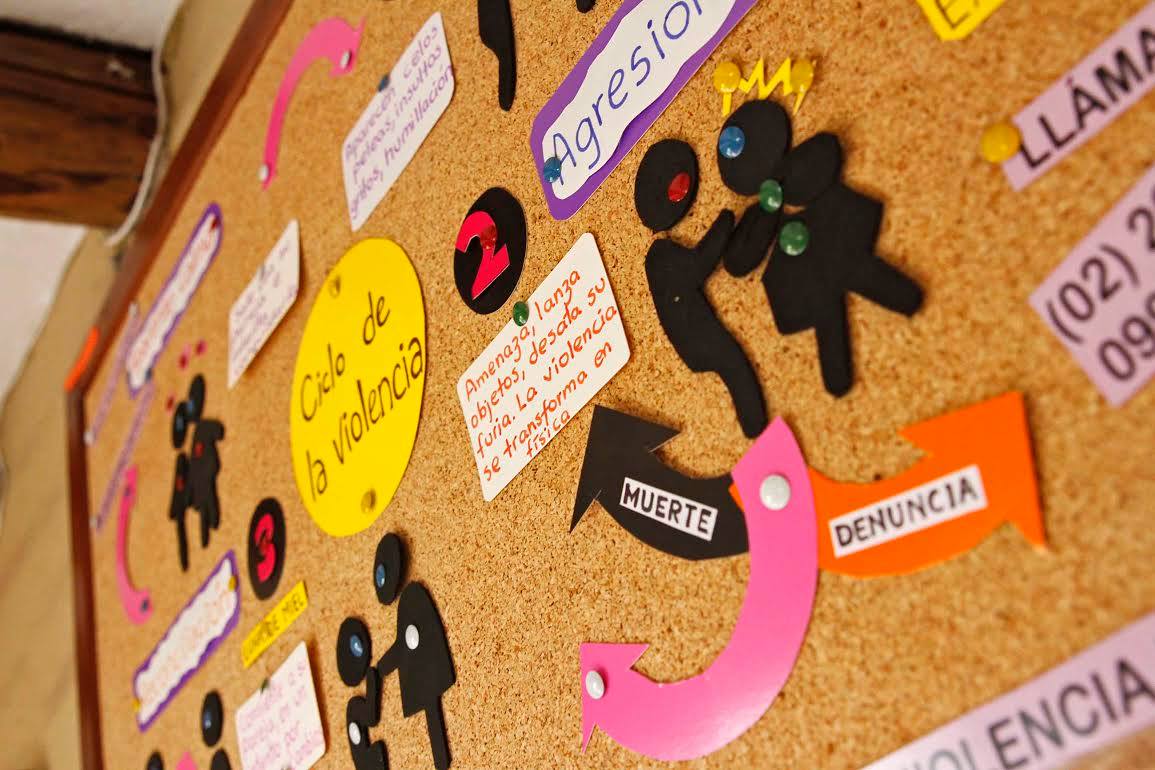

The cycle of violence. Photo from the ‘Casa de Refugio Matilde’ women’s shelter in Quito, Ecuador. Used with permission.

This article is part one of the author's report on women with violent partners during lockdown in Ecuador. Click here to read part two.

Elisa, whose name has been changed for her protection, is a 41-year-old Ecuadorian businesswoman in an abusive relationship. Although almost half of all women in Ecuador have endured this type of violence at least once in their lives, Elisa believes that abusive relationships are not really understood by the general public. In a phone interview with Global Voices, she explained:

Me dicen: ‘Solo déjalo’, pero no funciona así. Quien no ha pasado por esto no siempre entiende por qué es tan difícil dejar a una pareja violenta, y estos comentarios solo hacen que me sienta juzgada y deje de contar lo que me pasa. Yo he intentado separarme de mi pareja algunas veces, pero él se convirtió en el centro de mi universo. Por eso, a pesar de todo, sigo con él.

People say to me: “Just leave him”, but it doesn’t work like that. People who haven’t been through this don’t always understand why it’s so hard to leave a violent partner. Comments like that just make me feel like I’m being judged and I stop telling people what’s happening to me. I’ve tried to leave my partner a few times, but he became the centre of my universe. That’s why, despite everything, I stay with him.

Esteban Laso, a psychotherapist and social psychologist, explains that the difficulties Elisa describes are common; it is a complex process that can take many years and an average of 5 to 7 attempts. According to Laso, this is because ending any relationship (whether it is violent or not) is always hard, but violence introduces certain factors that make separation even more difficult.

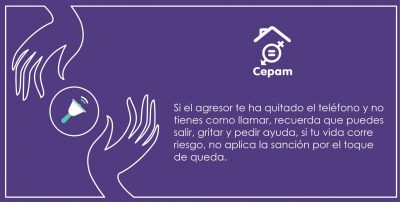

Care protocol for female victims of domestic violence. Shared on the Surkana Ecuador Facebook page.

These difficulties can increase in crisis situations, such as the pandemic that we are living through now. Ecuador has been under lockdown for over a month, with a curfew from 2pm to 5am. Lily Rodríguez, President of the Ecuadorian Centre for the Empowerment and Advancement of Women (CEPAM), says that domestic violence can increase because there are fewer opportunities to seek help or to offer support to women during the lockdown.

Rodríguez adds that emotional separation is essential to achieving physical separation, but this is made more difficult when victims are permanently living with their partners. Elisa says that this emotional dependency is the main reason that she is still with her partner:

Se piensa que solo es cuestión de tomar la decisión, pero no. Yo he decidido irme algunas veces, y he estado en terapia mucho tiempo, pero los hombres violentos son excelentes manipuladores y tienen mucha experiencia en hacer que te aferres a ellos. Esto hace muy complicado deshacer el lazo emocional que te ata a esa persona. Tú sabes que lo que te están haciendo está mal y que estás en peligro, pero tu dependencia hacia ellos es más fuerte.

People think that it’s simply a matter of making the decision, but it’s not. I’ve made the decision to leave many times and I’ve been in therapy for a long time, but violent men are excellent manipulators and they are very experienced in making you depend on them. This makes it very hard to undo the emotional link that ties you to that person. You know that what he is doing to you is wrong and that you are in danger, but your dependency on him is too strong.

Laso points out that we tend to believe that our decision-making process is guided by reason. However, this assumption is wrong:

El fundamento de las relaciones humanas es el amor. Sin amor nos morimos, entonces haremos lo que haga falta para evitar la pérdida de relaciones afectivas importantes, incluso si esto implica sacrificarse uno mismo. Por eso, la primera pregunta que se hace una mujer en una relación violenta no es si la debe abandonar o no, sino si su pareja puede cambiar.

The foundation of human relationships is love. We die without love, so we do whatever it takes to prevent the loss of important emotional relationships, even if that means sacrificing ourselves. Therefore, the first question that a woman in a violent relationships asks herself is not whether she should leave him, but whether her partner can change.

Soledad Ávila, clinical psychologist and academic director of Fundación Azulado in Ecuador, adds that abuse often starts with psychological violence. This type of abuse is harder to recognise and affects the victim’s self-esteem, thereby prohibiting her ability to leave the relationship. In addition to this, according to Ávila, the aggressor is not violent all the time. He also has his “good moments” in which he professes his “undying love” and offers to change. This cycle creates patterns that are difficult to break.

Recommendation from CEPAM Facebook page.

The fear that the violence will get worse when deciding to leave the relationship also hinders the process. This anxiety may increase during quarantine, in which restrictions on movement make it harder to seek and offer help against a threat. However, Rodríguez explains that in Ecuador people are allowed to leave and ask for help when faced with an imminent threat during lockdown.

Ávila adds that the cultural norms that underpin a structure of violence also have an influence:

Se promueve una posición pasiva de la mujer. Esto nos lleva a aguantar y pensar que, con paciencia, vamos a lograr que nos traten bien. Muchas veces no notamos estas ideas porque están muy arraigadas en la sociedad.

Women are encouraged to be passive. This leads us to endure certain situations and believe that, if we’re patient, eventually they'll treat us well. A lot of the time we don’t notice these ideas because they’re so entrenched in society.

These cultural norms are intertwined with economic and structural factors. For example, existing inequalities place women in a disadvantaged position of financial dependency. This often means that they cannot leave the relationship if they do not have enough money for themselves and their children, given that responsibility for childcare usually falls on women. Quarantine makes it increasingly difficult for them to generate this necessary income.

What’s more, despite Ecuador’s existing rules and protocols of care for victims of violence, Ávila identifies a lack of awareness by professionals in healthcare and the judiciary about this issue. This was the case for Elisa, who told GV:

Aparentemente tienes apoyo legal, pero existen muchas trabas que te desaniman. Cuando mi pareja me pegó por primera vez, fui a denunciarlo, pero fue terrible. El abogado me dijo: “Si vas a poner la denuncia tienes que seguir hasta el final y no puedes volver con él”. Yo no estaba lista para eso. Lo que te deberían decir es: “Tu vida está en peligro. Vamos a poner la denuncia juntos y vas a tener un acompañamiento psicológico y legal para que tú culmines este proceso”, pero te asustan en vez de darte este soporte.

You seemingly have legal support, but there are a lot of obstacles that put you off. When my partner hit me for the first time, I went to report him, but it went terribly. The lawyer said to me: “If you are going to report the crime, then you need to see it through to the end and you can’t go back to him”. I wasn’t ready for that. What they should say to you is: “Your life is in danger. We’re going to report the crime together and you’re going to have psychological and legal support to help you through to the end of this process”, but they scare you instead of offering you this support.

Rodríguez concludes that overcoming these challenges requires a combination of efforts, which has been highlighted by the quarantine:

Es fundamental que las mujeres no se sientan solas en el confinamiento; que sepan que estamos unidas de diferentes maneras, y que esta unión nos fortalece. Así, seguimos tejiendo hilos de solidaridad que aumentan nuestra resistencia colectiva hoy y siempre.

It’s vital that women do not feel that they’re alone during lockdown; that they know that we’re united in many different ways, and that this union makes us stronger. We therefore continue weaving the threads of solidarity that increase our collective resistance for now and for the future.