[1]

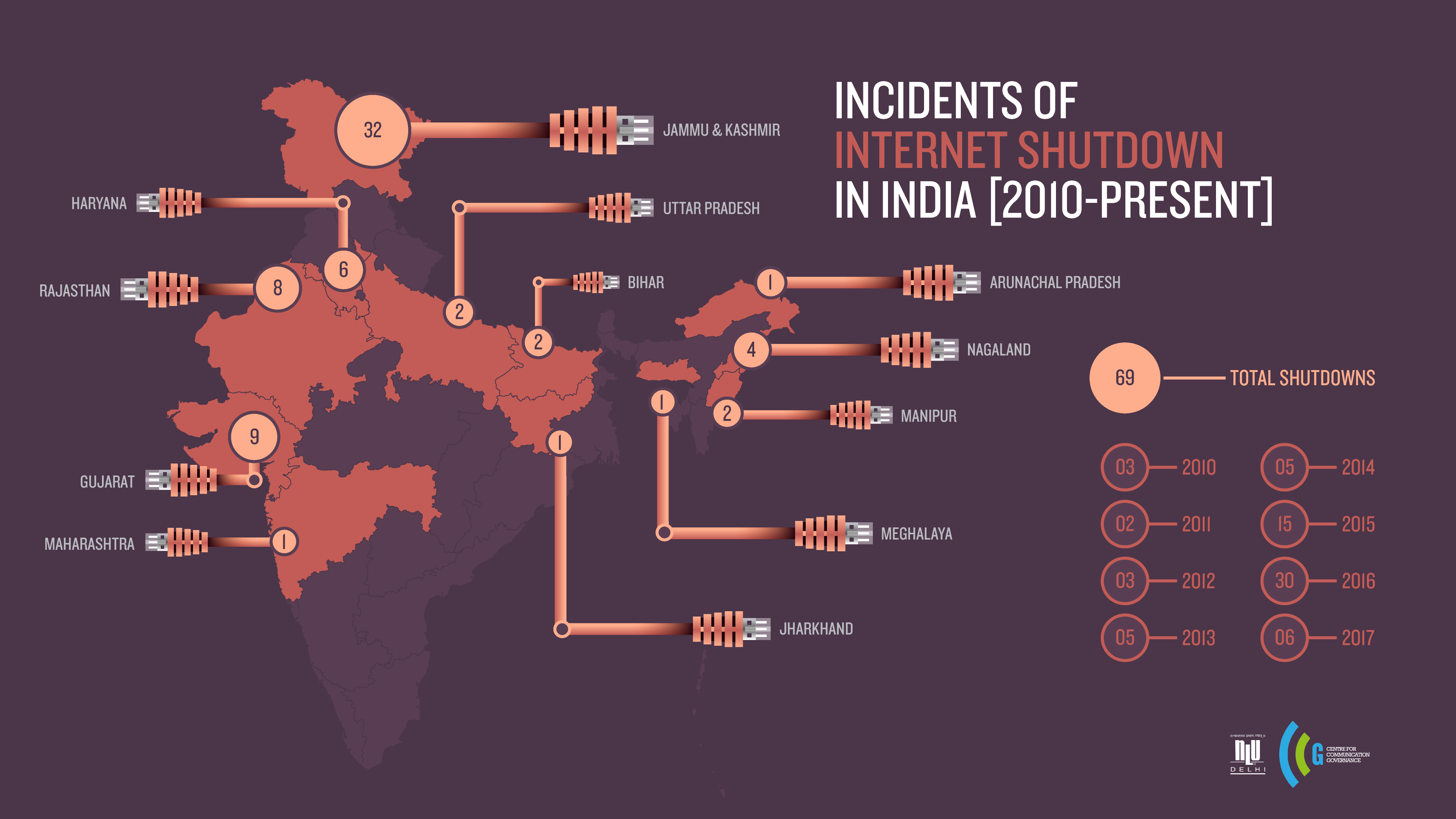

[1]India internet shutdown map, January 2010 – March 2017. Created by National Law University Delhi and the Centre for Communication Governance (CC BY)

India topped [2] the list of countries that shut down the internet in 2019 with a staggering 121 shutdowns, more than half the 213 events recorded around the world, according to digital rights advocacy group Access Now.

Globally, 33 countries switched off access as compared to 25 in 2018, the #KeepItOn report [3] on internet shutdowns in 2019 said.

1/ In collaboration with the #KeepitOn [4] Coalition, we have been documenting #internetshutdowns [5] since 2011. Today we launched our 2019 report. Below are some of the trends we observed ⬇️ https://t.co/pJdCf3em2J [6] pic.twitter.com/F2FMLJgOuX [7]

— Access Now (@accessnow) February 25, 2020 [8]

The shutdowns in 2019 were longer, geographically more targeted and included slowing down access to social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook.

Following India, Venezuela was a global leader for shutdowns, blocking access to social media platforms at least 12 times.

After Venezuela, Yemen, Iraq, Algeria, and Ethiopia were the countries with the most shutdowns.

Pakistan had five incidents of mobile or broadband services being switched off while Indonesia experienced three.

Myanmar imposed the year’s longest internet shutdown in its Rakhine and Chin states where 500,000-600,000 Rohingya Muslims reside.

Authorities in Bangladesh also shut down mobile internet connections in refugee camps where mostly Rohingyas reside. The shutdown has been imposed [9] since early September 2019 and it is still ongoing.

Governments justified their actions by claiming they were meant to help ensure public safety, increase national security and to stop the spread of fake news, among others.

Kashmir: the world’s second-longest shutdown in 2019

After scrapping [10] the special provisions from its constitution regarding the Jammu and Kashmir state, the Indian government banned public gatherings, detained local leaders, cut off telephone lines and imposed [11] a complete blackout of the internet for 175 days — the second-longest shutdown globally in 2019.

It was also among the longest shutdowns recorded in India to date.

Some of these restrictions were lifted after India’s Supreme Court criticized [12] the shutdown, termed indefinite internet blackouts unconstitutional and asked authorities for a policy revisit.

The ruling, however, failed to provide any immediate relief.

As of now, residents in India-administered Kashmir are only allowed [13] to access slow 2G internet connections, are blocked from accessing most social media platforms, and can only visit white-listed websites that are vetted by the government.

Besides Kashmir, #KeepItOn documented incidents of internet shutdowns in other Indian states “to stifle dissenting voices.”

Petitions were launched [14] across high courts in different Indian states challenging the shutdowns ordered following nation-wide protests against the controversial Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the proposed National Register of Citizens in Assam.

While a court in Gawuhati city forced [15] the Assam state government on December 20, 2019, to restore internet connectivity, which was disconnected on December 11, 2019, after demonstrations in 10 state districts, a court in Kerala also ruled [16] on September 19, 2019 in favour of a petition requesting right to internet access in a girls’ hostel at night.

“Shutdowns in Jammu and Kashmir comprised about 68% of the shutdowns in India, followed by Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and West Bengal,” Access Now said.

The most common government rationale for shutting down the internet in India was “precautionary measure” or restoring public order.

The network restrictions, the report said, have served to hide a series of egregious human rights violations in Kashmir such as detaining and beating children, and restricting travel and access to the disputed region.

The full report can be accessed here [3].