The landmark Gandan monastery in the centre of the Mongolian capital Ulaanbaatar. Photo (c): Filip Noubel, used with permission

Sandwiched between Russia and China, Mongolia is a large but sparsely populated country whose long and bitterly cold winters provide ample time for reading. As Mongolia marks the 30th anniversary of its transition from state socialism to a free market economy, its publishing market has evolved to reflect the priorities of a more internationally connected society.

Bookshelves in Ulaanbaatar are heaving with international literature in translation, and new local authors writing in their native language. So, what are Mongolians reading?

From monopoly to plurality

In 1924, Mongolia became the world's second country after the Soviet Union to adopt state socialism as its ideology. Its ties to Moscow were so close, and its relations with its southern neighbour China so frosty, that Mongolia was often described in the 20th century as the “16th Soviet Republic” (the Soviet Union itself comprised 15). That all changed in 1990, when from January to March, Mongolia underwent its own glasnost-inspired revolution, embracing a democratic system based on political plurality and market economy.

One of the sectors deeply affected by the sudden changes was publishing. Under socialism, the content of books, newspapers, and magazines was tightly censored and shaped by ideological control from Moscow. With the revolution, that system collapsed. The resulting free-for-all meant greater freedom of expression, but it also spelled an end to state subsidies for book production and distribution. According to Bayasgalan Batsuuri, a writer and literary translator who co-founded the independent Tagtaa Publishing house:

After the democratic revolution of 1990, due to the closure of the state owned publishing factory, we experienced a whole decade of dark years. We had nothing to read but leftover books from the socialist period. But from early 2000, several private companies emerged and started to rebuild the industry. Now we have five big private publishing companies, and more than 40 independent publishing houses. I think that today, the publishing industry is one of the rising sectors of Mongolia.

Example of the traditional Mongolian alphabet. Photo (c): Filip Noubel, used with permission.

Therefore, the outlook appears positive. But there are obstacles. While there are over six million Mongolian speakers in the world, the Mongolian language book market is sharply divided because of differences in alphabets. Mongolia uses a Cyrillic alphabet, imposed by Moscow in 1940, which is used by the country's three million inhabitants.

Meanwhile, around six million Mongols live in China, roughly half of whom speak their ancestral language. China is also home to the Autonomous Region of Inner Mongolia, where the traditional Mongolian alphabet is in official use. Also known as “Bichig,” it was inspired by the old Uyghur script, and is written in vertical lines from top to bottom.

According to a survey conducted by Batsuuri in 2019, over 600 books are published every year in Mongolia, for an average price of 7.5 US dollars for paperbacks, and 14 USD for hardbacks. This makes books rather expensive, given that the average monthly salary is below 400 USD.

The same survey mentions that nearly two thirds of these titles are domestic works and one third are translations. Most readers are aged between 21 and 38.

The majority of bookshops are concentrated in the capital Ulaanbaatar where over one-third of the country's population lives. Nevertheless, online reading and ebooks are also taking off.

History buffs and armchair travellers

Two major topics of interest seem to shape reading habits in Mongolia: national history and big names in global literature. The first is related to a legacy of heavy censorship under state socialist rule. After Stalinist purges in the late 1930s that led to the death of over 30,000 “enemies of the people” or ideological opponents, the Mongolian Communist Party imposed a rewriting of national identity that erased large parts of the country's history, Buddhist culture, literature, and art. Many Mongolians are still rediscovering forbidden parts of their heritage today, thus prompting a large demand for books about history and traditions, as Baatsuri explains:

Historical novels are more popular: after centuries of external pressure and lost identities, our people have an inevitable need to recover their national from their history.

Publisher and translator Bayasgalan Batsuuri holds a Mongolian translation of Chinese author Yu Hua. Photo used with permission.

Similarly, Batsuuri makes sense of the popularity of translated literature by way of Mongolia's historical traditions:

Mongolia has a very rich history of translation. The first recorded translations are from the third century BCE, when our ancestors translated mainly religious manuscripts from Sanskrit, Uyghur, Tibetan, Chinese, Persian, and Arabic classical literature. During the socialist period, Russian classics and Soviet literature were translated under strict censorship.

These days, Mongolians are free to travel, migrate, and publish leading figures from contemporary world literature. Japan's Murakami Haruki, Turkey's Orhan Pamuk, and China's Yu Hua are all popular choices, as are the world classics such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Ernest Hemingway, and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Consequently, Mongolians have access to a greater choice of literature than ever before. Many of these names would have been unthinkable under socialism. But what has been gained in diversity is sometimes lost in the quality of these translations, warns Oyunzul Ariunbold, a 24-year-old translator and literary activist who ran a book club for several years in Ulaanbaatar.

Translator Oyunzul Ariunbold. Photo (c): Namuunsuren Tsendsuren, used with permission.

Before 1990, the state commissioned translations. That meant that the books had high standards: there was meticulous editing and proofreading. Today, some people say that the quality of books has gone down, and that translated works can be unreadable, blaming young translators. There is some truth in this criticism, but it’s getting better. And I'm just grateful that a reading culture is growing amongst young people, so that for example, my niece can read “To Kill a Mockingbird” in Mongolian.

Ariunbold agrees that Mongolia's independent publishers are aiming for true diversity:

A lot of emphasis is given to modern classics. Basically, we are just catching up with modern literature. One publishing house, for example, publishes only one author per country per year, to avoid ending up offering only white male authors from Europe.

Paper is popular

Despite steep prices, and the variety of other forms of entertainment available now with the internet, cable television, Mongolians value paper books. Mongolia's reading culture seems strongly established, particularly as self-published books enjoy great popularity, as Batsuuri explains:

In our culture, books are very respected, and during the Soviet period, the reading culture developed intensively. For a population of three million, our national bestselling record was 95,000 copies: a book by a Mongolian author who self-published. In 2019, our company published Yu Hua's novel “To live” (活着) and we've already sold 12,000 copies.

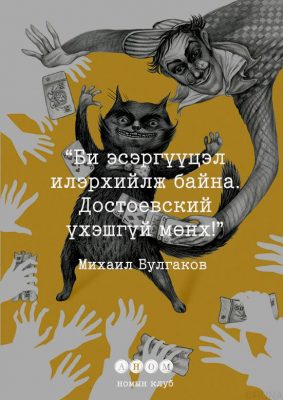

Image designed by Oyunzul for her Book Club Facebook page. “I protest, Dostoyevsky is immortal,” reads this quote from Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov's famous novel, The Master and Margarita. Used with permission.

Oyunzul Ariunbold shares this impression:

Nobody expected “Madonna in a Fur Coat,” by Turkish author Sabahattin Ali, to become so popular, and yet it did. People are in need of emotional books, stories of vulnerability when society expects them to be tough and stoic. People are definitely using their phones and tablets to read, but we still have huge respect for paperbacks.

Perhaps the biggest change in Mongolia's reading culture in recent years has come from the phenomenon of self-publishing. As poet and journalist Yesunerdene Tumurbaatar explained to Global Voices:

If you have a bit of money, it's easy to print your own book yourself. Usually people print a thousand, then either sell them directly to bookstores or at their own events.

We organise events where we read poetry and perform music. That's how I sold two collections of my poems.

For now, at least, it seems that Mongolians have plenty to take their minds off those punishing winters.