Global Voices quinceañera: When the Caribbean did the right thing

In this final installment of the series honouring Global Voices’ 15th birthday, we highlight the stories in which people spoke out on tough matters that have been plaguing the region, or stood on the right side of history.

Rethinking education

Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Mottley gives a speech at the 108th (Centenary) Session of the International Labour Conference in Geneva, Switzerland, on June 19, 2019. Photo by Crozet / Pouteau, used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

In June 2019, Barbados’ prime minister Mia Mottley, who is proving herself to be one of the most forward-thinking in the region, announced that, in an effort to create more diverse and equitable educational opportunities for schoolchildren, her administration plans to get rid of the controversial Common Entrance exam.

Secondary school entrance examinations in the Caribbean have been around for over a century, a colonial holdover from as early as 1879 in some territories. Though renamed and restructured several times, they have remained as what many experts deem an irrelevant, stress-inducing test that sucks the joy out of learning for 11-year-olds region-wide.

Under the current secondary entrance exam structure, only the top performing students — essentially, those who test well — win access to the best schools. Class often becomes a factor, since parents with good social connections often pull strings to get their children into schools of their choice. Prime Minister Mottley's position is that Barbados must “create an educational system that makes every school a top school” — reform that includes moving away from a curriculum that is heavily slanted towards academics, to include more technical, vocational and arts training.

In other regional territories like Trinidad and Tobago, in addition to laments about the negative effects of such an exam, there have been calls for more inclusivity for special needs children, who tend to be inadequately supported by the public school system.

If Barbados succeeds in this endeavour, it would be history-making; other governments in other CARICOM nations have promised to abolish the exam before and failed.

Speaking out against corruption

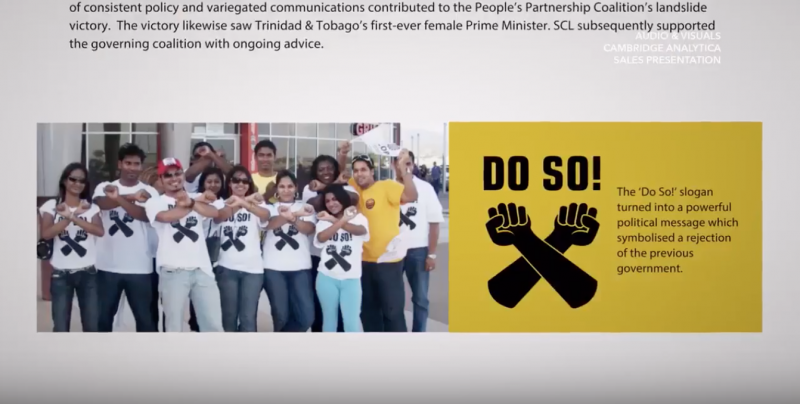

Screenshot taken from a YouTube video, showing an excerpt from “The Great Hack” related to Cambridge Analytica's alleged work during Trinidad and Tobago's 2010 general elections.

Corruption is one of the root causes of many of the problems regional societies face — from inadequate social services to rising crime rates. Realising this, people across the Caribbean have been speaking out — from Haiti's street protests against the continuing fallout from the PetroCaribe scandal to the arrest of a Trinidadian government official for money laundering, conspiracy to defraud, and misbehaviour in public office.

In fact, Trinidad and Tobago featured heavily in all the corruption stories we worked on this year. Public pressure was integral in forcing the government to drop proposed “undemocratic” amendments to the country's Freedom of Information Act and, after a union leader was charged with sedition, widespread debate ensued about freedom of speech, forcing the government to rethink the Sedition Act.

After Netflix's documentary, “The Great Hack,” premiered in July 2019, discussion was rife over Cambridge Analytica's role in Trinidad and Tobago's 2010 elections, renewing concerns about the ease with which corruption and voter manipulation can go hand in hand.

Even though the Cambridge Analytica scandal was widely reported on globally, the issue of how the company helped manipulate the electoral process in developing nations has been underreported, despite the majority of the company's elections-based clients having been from the Global South — but with Caribbean netizens speaking out about it, awareness of the dangers has now been raised in the region.

Honouring First Peoples

Visiting Surinamese Lokono people (Arawaks) at the reinterment ceremony of the First Peoples’ bones at the Red House in Port of Spain, Trinidad, October 19, 2019. Photo by Maria Nunes, used with permission.

This year, the importance of the legacy of the region's Indigenous peoples came through very strongly. Jamaica, for instance, has been experiencing a resurgence of interest in Taino (or Arawak) history: For the first time in 500 years, Jamaica has its first Taino chief (cacique), who was installed in June 2019. A month earlier, the Institute of Jamaica celebrated Taino Day with talks and activities, including the launch of a new illustrated children's book.

Even more significantly, the Jamaican government has been working — via the National Commission on Reparations — to have world-renowned wooden Taino artefacts returned to Jamaica from Britain. Minister of Culture, Gender, Entertainment and Sport, Olivia Grange, who has been spearheading the effort, said of the artefacts:

They are priceless, they are significant to the story of Jamaica, and they belong to the people of Jamaica.

This despite questions over whether or not Jamaican is doing its best to preserve what is left of its indigenous legacy, given the lack of a dedicated Taino museum and concerns over the degree of protection that Taino sites in the country are afforded.

At the southern end of the archipelago, meanwhile, in Trinidad and Tobago, there was an outcry over the proposed name change of the country's airport from Piarco (an Indigenous name) to one honouring the country's first prime minister. But by far the most moving event was the reinterment of the remains of Trinidad and Tobago's First Peoples.

When the restoration of Trinidad and Tobago's Red House — the seat of the country's parliament before the building fell into disrepair — began back in 2013, construction workers found the bones of as many as 60 Tainos. In a long-awaited reinternment ceremony on October 19, 2019, their remains — which date back to anywhere from 125-1395 AD — were finally laid to rest once more.

For the First Peoples community, it was a reclamation of an important piece of their past. At the reinternment ceremony, the Santa Rosa First Peoples’ Chief, Ricardo Bharath-Hernandez, said it was a way for their ancestors to speak to them and a moment to properly commemorate their dead:

Some may look at this ceremony as something that does not matter, neither important nor significant. But just as most of us treat our dead with respect, and use the appropriate rituals in their own tradition, we feel very strongly that the remains of our ancestors should be respected and treated likewise.

Since no country — or region — can go boldly into the future without knowing and understanding its own history, such rekindling of respect for where we have come from as Caribbean people forges a strong sense of hope for where we might go in 2020.

Support our work

Global Voices stands out as one of the earliest and strongest examples of how media committed to building community and defending human rights can positively influence how people experience events happening beyond their own communities and national borders.

Please consider making a donation to help us continue this work.