The Global Voices 15th birthday [1] celebrations continue, as we take a look at three 2019 stories that demonstrated ways in which the region evolved by going against the grain of traditional Caribbean society.

‘Queer as quantum joy’

[2]

[2]Pride parade in Port of Spain Trinidad on July 31, 2019. Photo by Maria Nunes. Used with permission.

On the occasion of the country's second annual pride celebrations, Trinidadian poet Shivanee Ramlochan posted a powerful essay [3] on Facebook that perfectly encapsulated both the freedom of being unapologetically out and the tough road it took to get there.

Pride is beautiful. And it is political. And it is born of a bloody, mutinous theirstory, from the roots of a radical understanding that acceptance was not the only striveable goal, at least not acceptance from the come-to-Christer, from the corporation, from the oligarchy, from the evangelical, from the elite. And so whether your body was visible in the parade, or not, to exist queerly is its own breathtaking defiance of the statutes of raw hatred. You are alive. All the cells in you, incandescently gay. Irrepressibly lesbian. Outstandingly bisexual. Terrifically transgender. Indisputably intersex. Notwithstanding societal bullshit, non-binary. Queer as quantum joy.

Being gay in a region where so many territories still have “buggery” [4] laws on the books is a challenge, but the fact that pride parades have been successfully pulled off — in Barbados [5], Guyana [6], and Trinidad and Tobago [7] — leaves room for the hope that diversity will not only be tolerated but appreciated.

‘Freeing up the herb’

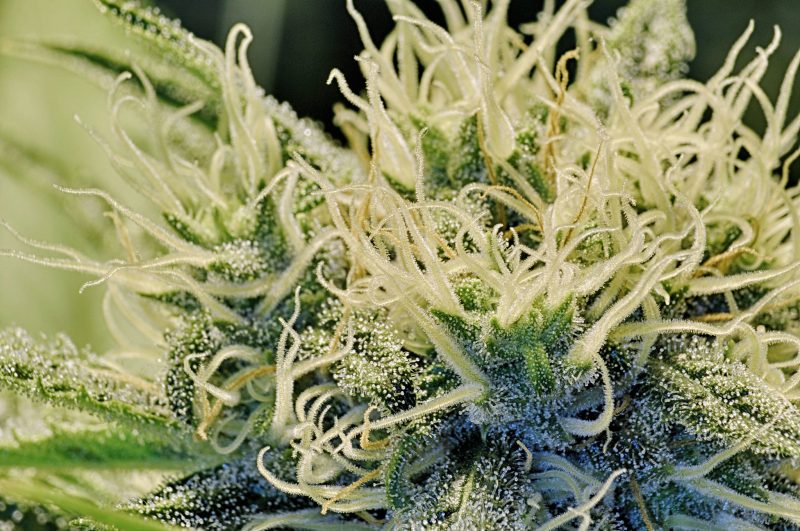

As far back as 2014, the Caribbean was in the midst of a debate [9] about marijuana legalisation. Jamaica eventually passed decriminalisation legislation [10] in February 2015; the measure was welcomed [11] as a kind of emancipation.

For the Caribbean, the idea of legal marijuana sales, purchase and consumption finally [12] seemed to be an idea whose time had come [13]; it was now a question of which countries would follow Jamaica's lead — and when.

Trinidad and Tobago was making moves [14] to decriminalise, pushed along by longtime cannabis advocates like Nazma Muller [15], who was arrested [16] outside parliament in October while continuing to press for the enactment of existing medical marijuana legislation [17]. She saw this as a forerunner to decriminalisation, which has taken longer than promised [18]. In the interim, people [19] were still arrested and sentenced [20] for marijuana possession.

As the marijuana bill was set to go to the country's cabinet [21] in early November 2019, advocates focused on how to get those charged with possession of small amounts of marijuana out of the criminal system [22].

Trinidad and Tobago's marijuana decriminalisation legislation will finally be proclaimed [23] on December 23 [24]. However, controversy is brewing over an alleged conflict of interest [25] with Attorney-General Faris Al Rawi, who piloted the bill. Members of the AG's family have allegedly registered [26] a for-profit entity called West Indian Cannabis Company, while, according to Muller [27], “cannabis is still illegal in T&T”:

The Attorney General must explain how his Ministry registered a company to engage in promoting — and possibly selling — an illegal substance, for which citizens have been jailed.

When the matter was raised in parliament, Al Rawi replied [28], “It is a fantasy that I could have any pecuniary interest in debating this bill. My wife has a very large family and I can’t claim to know what they do.”

Even with the imminent passing of the legislation, it seems that the controversy over marijuana in Trinidad and Tobago isn't quite over.

Reparations realised

Redemption Song Statue, Emancipation Park, Jamaica. Photo by Mark Franco, used with permission.

The concept of reparations for the injustices of slavery is one that has held a lot of traction in the Caribbean. In October 2015, when then-British Prime Minister David Cameron visited Jamaica, the topic was raised — and dismissed out of hand [29] with Cameron's admonishment for Jamaican to just “get over slavery.”

In response to “the whole idea of this dough-faced Tory coming to the colonies to tell the subjects what's what in our own damn house,” acclaimed Jamaican author [30] Marlon James said [31]:

Listen David bae, I feel you. I'm with you on this forgetting slavery business, screw all the haters. I too am all ready to move past slavery and forget the whole thing.

I just have one condition: YOU FIRST.

You heard me. I promise to stop bitching about the legacy of Slavery and Colonialism (don't get it twisted, the latter was even worse) and move on if you also move on, by destroying every building, every landmark, every statue, every port, every bridge, every road, every house, every palace, every mansion, every gallery (Hello, Tate!), every museum, and every ship built with slavery and colonialism blood money.

That would mean that London, Bristol and Liverpool would all have to go.

Then we'd all be just about full free, David.

Such calls for reparations are not new [32]. Guyana was the first CARICOM territory to speak out on the issue. In 2011, Antigua and Barbuda made a stirring plea [33] for reparations at the United Nations and the following year, both Jamaica and Barbados established reparation commissions [34], charged with leading the lobby for both formal apologies for the horrors and inhumanity of slavery as well as economic justice for descendants of slaves.

Finally, on July 31, 2019, their efforts met with success as vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies, Professor Sir Hilary Beckles [35], and the University of Glasgow’s Chief Operating Officer, Dr. David Duncan, signed a historic agreement [36] for slavery reparations — the first such contract since people enslaved by the British were fully emancipated [37]in 1838.

Never before has a UK-based institution that profited from slavery [38] apologised for its role [39] — and proven its remorse by showing the money — in this case, £20 million ($24,308,500 United States dollar). Symbolic of the sum [40] the British government paid to slave owners as compensation for the abolition of slavery, the money will be used for research and other development-based initiatives between the two universities over the next 20 years, under the auspices of the Glasgow-Caribbean Centre for Development Research [41], which is to be jointly owned and managed.

Three months later, the prime minister of Antigua and Barbuda, Gaston Browne, wrote to Harvard University President Lawrence Bacow, asking the Ivy league university to live up to its responsibilities and pay his country reparations for the school's historical ties to — and profiteering from — the transatlantic slave trade.

Browne maintained that reparations were owed to Antigua and Barbuda on account of the fact that Isaac Royall Jr. [42], an American slave trader and landowner who also operated in Antigua, bequeathed money to Harvard to establish its first law professorship, which later led to the creation of the Harvard Law School [43] in 1817. He is hoping to have the reparations put toward education — specifically The University of West Indies at Five Islands [44].

To make matters worse, in celebration of the university's tercentenary in 1936, Harvard Law turned Royall's shield into the school's official seal — a hugely controversial decision. In 2016, Harvard students protested [45] to have the crest removed, calling it “a glorification of and a memorial to one of the largest and most brutal slave owners in Massachusetts.”

The seal was eventually removed [46], and Harvard's former president, Drew Faust, declared [47] the university's ongoing commitment to acknowledging its ties to slavery, a fact that the current president mentioned in his response [48] to Browne.

Thus far, there has been no confirmation [48] as to whether or not Harvard intends to follow the example set by the University of Glasgow, but whether or not the attempt is successful, there is no disputing that the Caribbean has performed admirably this year in tackling an issue for which the Global North — despite its profiteering from slavery, colonialism and other injustices in the region — is still reluctant to make amends.