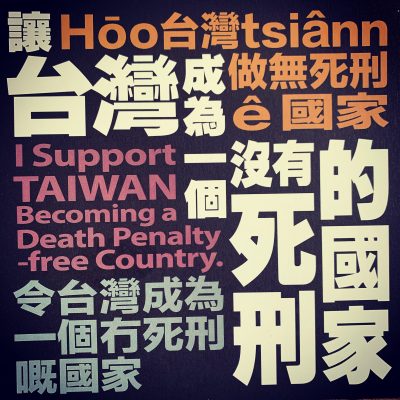

Leaflet from the Taiwan Alliance to End Death Penalty calling for the abolition of capital punishment in Chinese and English. Photo by Filip Noubel, used with permission.

Despite being recognized as the third most advanced democracy [1] in Asia, Taiwan still maintains the death penalty. On the surface, there seems to be a general consensus on the issue: 85 percent of Taiwanese [2] support it according to recurrent polls. Yet some activists believe the time has come to revisit the issue of capital punishment, particularly as the island gears up for presidential elections in January 2020 [3].

Worldwide, the death penalty has been abolished in over 100 countries [4]as it is considered a major violation of human rights [4]. In East Asia, allowing capital punishment is the rule and not the exception: Mongolia [5] abolished it in 2016, preceded only by Macao [6]in 1976 and Hong Kong [7] in 1993; all other countries apply it, including China where thousands of people [8] are sentenced every year.

In Taiwan, the death penalty was introduced when the island was under Japanese rule [9] (1895-1945). When the Kuomintang sought refuge [10]from mainland China in 1945 and resumed state control over the island, it maintained capital punishment. To this day, executions are carried out with the inmate sedated and shot in the back as he or she lies down on a mattress.

The death penalty is applicable to serious crimes, [11] such as treason, espionage, murder, or rape. The number of executions [12]has been consistently going down from about 50 to 70 a year leading up to the early 1990s, to around 5 per year on average since 2000.

If crime rates in Taiwan are among the lowest in the world, [13]why then are people in Taiwan overwhelmingly in favor of capital punishment? Lin Hsinyi, a long time anti-capital punishment campaigner who heads the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty [14](廢除死刑推動聯盟) and also works with former death row inmates, believes one of the reasons is that people lack the will to challenge existing norms:

台灣人習慣已經存在的事情。他們不太會思考,到底對不對。還有一些比較傳統的概念, 比如說,殺人要償命。但是我覺得我們沒有思考說,它存在就有道理嗎?台灣人很喜歡聽政府的規定。當然有些冤案, 可是這不是廣泛為人所知。

Taiwanese people are used to accept existing situations, they won’t necessarily spend time overthinking the matter to assess if it is correct or not. Traditional views do play a role here, for example the notion that ‘if you kill someone, you have to pay with your life’. But I think the real issue is that we haven’t processed one question enough: Is it because something exists that it is therefore right? People in Taiwan are very much inclined to obey government rules. Of course there have been cases of miscarriage of justice, but the broad public wouldn’t know about those.

In an effort to change the norms, the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty (TAEDP) has worked with government structures and researchers to frame the issue in a more nuanced way that goes beyond the idea of just “being for or against” capital punishment. The results of a 2013-2014 questionnaire, [15]which included over 100 questions and polled 2,000 people indicated that people's positions are not as entrenched as they would appear. Lin Hsinyi explains:

你問人們有冤案的情況的話, 他就更不想判死刑, 所以支持死刑並不是一個理性思考的想法。我們做了一個很走趣的事情,我們做了兩套問卷,分成A和B。在A的問卷,我們把‘你支持不支持死刑“的問題放在前面的地方, 在B問卷,把同樣的問題放在最後面。 你會發現, 如果人花時間考慮, 82%的人會支持死刑,如果問題放在前面,這個比例是88%, 大概有6%的差異,說明15分鐘的區別就可以造成怎麼大的改變。如果我們提供更多的資訊, 如果我們教育民眾, 應該可以改變。

所以如果你有選擇的可能性的話,大家會不選擇死刑。政府經常說“因為民意支持死刑,我們要執行死刑”,我覺得這是錯的。你要做政府,你是不是要跟我講,有其他的方案? 廢除死刑最大的困難不是民意,是不負責任的政府,不管是民進黨還是國民黨。

If you ask people about cases of miscarriage of justice, then they are not in favor of death penalty, thus the support for capital punishment is not at all based on rational thinking. We did a very interesting thing, we divided the questionnaire into type A and B. In questionnaire A, we put the question ‘do you support the death penalty or not?’ at the top, while in questionnaire B this question appeared at the very end. We discovered that if people spend time to think over it, only 82 percent of the respondents would support death penalty, while if you ask at the beginning, the rate in favor is 88 percent. There is a gap of about 6 percent. This shows that a difference of 15 minutes of time is enough to create such a change in opinions. If we provide more information, if we educate the public, we can certainly change perceptions.

Thus when given the possibility of choice, most people do not opt for the death penalty. The government often says ‘we implement the death penalty because the public supports it’. But this is wrong in my opinion. If you are the government, shouldn't your role be to explain, to provide alternatives? The biggest obstacle to the abolition of the death penalty is not public opinion, it is the government that fails its responsibilities, be it a DDPor KMT [government].

The reintegration of former death row inmates who have been freed once a judiciary error has been recognized by the state is an important part of the work Lin Hsi-yi and her organization undertake. As she explains:

政府每天會賠償一千到五千台幣,但是到找NGO之前,他們(這些冤案的受害者)要自己找律師, 家人也不能工作為了要幫忙他們,所以拿了賠償之後,他們要把錢還給家人, 其實很快就沒錢了。

The government will compensate from 1,000 to 5,000 Taiwanese dollars per day [about US$ 32 to 160 for every day spent in prison]. But before they find an NGO to help, they have to pay for their own lawyers, their family members have to support them and cannot go to work, so once they receive the compensation, they have to return the money to their families and use up all the money very soon.

While some of the former inmates work in NGOs advocating the abolition of the death penalty, others choose manual work as part of their therapy to overcome their trauma. One of them is Cheng [16]Hsin-tze who was wrongly accused of murdering a police officer. He spent 16 years in a prison in Taiwan, 12 of those years were spent on death row. Now, Cheng [16]Hsin-tze grows and sells organic rice.

Organic rice produced by former death row inmate Cheng Hsin-tse. Photo by Filip Noubel, used with permission.

Some also become spokespersons for the abolition campaign. At a photo exhibition opened recently in Taipei, the work of artist Christophe Meireis [17] profiled the lives of inmates and their relatives and was attended by Hsu Tzu-chiang. [18]

Hsu Tzu-chiang speaking at the opening of a photo exhibition of death row inmates in Taipei on November 15, 2019. His own portrait is exhibited as well with the following quote: “I don't have dreams. I just wish that there won't be another Hsu Tzu-chiang.” Photo by Filip Noubel, used with permission.

The death penalty regularly resurfaces in public discourse around election time in Taiwan. In 2000, the island experienced a major political shift as the Democratic Progressive Party [19] (DPP) ended the 55-year long political dominance of the Kuomintang with the election of DPP President Chen Shui-bian [20]. From then on, the issue has been instrumentalized around election time [21] as competing parties are courting voters and want to appear as hard-liners on issues of safety. This despite the fact that in 2009, Taiwan ratified [22] the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which calls for the abolition of capital punishment. However, since it signed the agreement, Taiwan has applied the death penalty in 34 cases [12], both under KMT and DPP governments.

The main question now is how the winner of the January 2020 Presidential elections will consider the issue of a moratorium. As the experience of other countries show, a prolonged moratorium is the most successful way for the abolition of capital punishment, as illustrated in this region with Mongolia.