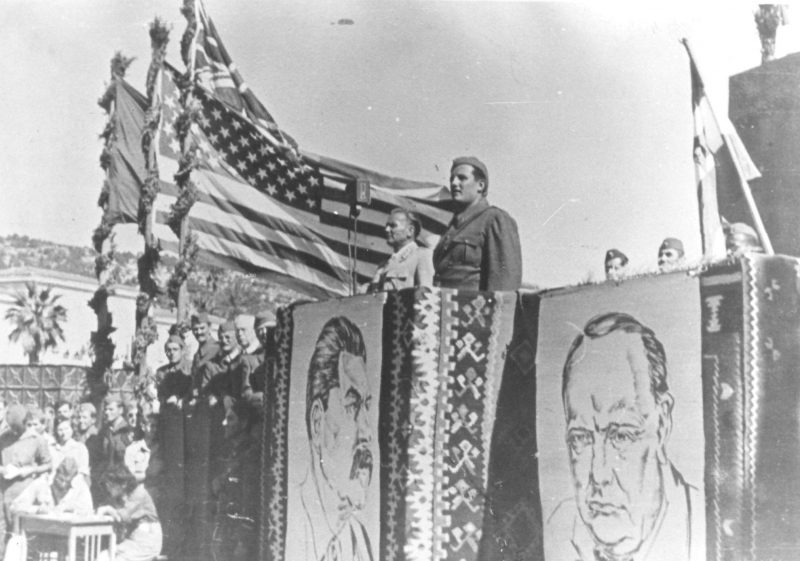

A Yugoslav Partisans celebration featuring Josip Broz Tito with the flags of all their allies: the USA, the USSR, and the UK; as well as portraits of allied leaders (out of frame) Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill. Vis, Croatia, 9 November 1944. Photo: znaci.net, public domain.

While reporting on the ratification of the protocol for North Macedonia's NATO accession in the US Congress on October 22, US website The Hill incorrectly asserted that Yugoslavia was an ally of the Soviet Union. This historical fallacy, frequently found in Western media, is considered an offensive stereotype by many citizens of post-Yugoslav countries.

The Hill is an influential publication in Washington DC and is read by top decision-makers in the United States. In fact, the article in question was tweeted by former US vice president, Senator Joe Biden.

I strongly support the Senate's approval of North Macedonia's NATO membership. The countries of the Western Balkans deserve to be part of a Europe whole, free and at peace and we should be supporting Euro-Atlantic integration across the region. https://t.co/UUyOWL20z7

— Joe Biden (@JoeBiden) October 24, 2019

While the article is accurate for the most part, its background section includes the following sentence:

Previously part of Soviet ally Yugoslavia, North Macedonia, was formally invited by NATO in July 2018 to start accession talks and 22 countries have since ratified its accession.

For most of its existence, the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia was not a Soviet ally – on the contrary, its independence from both the Eastern and the Western blocs was a key feature of its national identity.

Yugoslavia was established in 1943 at the height of the Second World War by the Yugoslav Partisans, the communist-led anti-fascist resistance which was supported by the Allies. While they received assistance from the US, the UK, and the USSR, the Yugoslav Partisans liberated large portions of the Axis-occupied country on their own. It was only in this broader sense that Yugoslavia was a formal ally of the Soviet Union – alongside all the other allies.

After the war, the relations between the two communist parties deteriorated. By 1948, the Yugoslavs renounced Stalinism in order to create a distinct form of socialism. And between 1948 and 1955, during the Informbiro period, Yugoslavia was in direct opposition with the Soviets, to the point of preparing to fight off an invasion by the Warsaw Pact.

German soldiers passing by anti-fascist graffiti “Long live our allies: USSR, England, America!” after they temporarily re-occupied the Croatian island of Hvar on 2 April 1944. Source: znaci.net, public domain.

As evidenced by information released by John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, Yugoslavia heavily relied on US aid during the post-war period — for example, by receiving food supplies from the United States Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, which prevented mass famine in 1945. For part of its history, the US bestowed on Yugoslavia the status of the “most privileged nation” in trade, which boosted the Balkan country’s economic growth.

As part of its balancing act between the blocs, Yugoslavia was one of the founders of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961. Unlike East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria, it was on the western side of the Iron Curtain, the so-called line dividing the Soviet-dominated zone from the rest of Europe.

The incorrect assertion that equates Yugoslavia with the Soviet Union has popped up from time to time in Western media, mostly in its right-wing sphere. When intentional, it's constituent of a modern-day Red Scare discourse which degrades the reputation of political actors from the region. That discourse is usually aimed at conservative Western audiences who are still sensitive to “the communist threat.”

For instance, in October 2015, The Hill published an article by a lobbyist paid by VMRO-DPMNE, a Kremlin-friendly nationalist party that ruled North Macedonia from 2006 to 2017, that attempts to smear its pro-EU and pro-NATO opponents as pro-Russian. It says that Macedonia was “a former Soviet bloc country” whose “domestic opposition party, SDSM, is led by Zoran Zaev, the successor to the former ruling communist party during the Cold War.”

A 2016 article in the same publication, loaded with narratives pandering to right-wing concerns about migration, misrepresented Zaev as a “culprit” for Balkan instability and “the head of the Russia-leaning SDSM Socialist Party.”

This language speaks to conservative mainstream audiences in the West, for whom the term “socialist” is loaded with negative connotations and is inherently associated with the USSR and, by extension, Russia. However, that language finds no bearing in North Macedonia itself. SDSM stands for Social Democratic Union of Macedonia, and its center-left platform is explicitly pro-NATO and pro-European. Proof of that is Zaev's signing of the Prespa Agreement in 2018, which ended a historic name dispute with Greece, and whose primary outcome would be North Macedonia's accession to NATO and the European Union. Meanwhile, an actual Socialist Party was a member of the VMRO-DPMNE coalition of populist nationalists, which spanned the political spectrum.

Yugoslavia between blocs

Besides its fallaciousness, equating Yugoslavia to the Soviet Union or its bloc is seen by many former Yugoslavs as a negative stereotype. Almost three decades after the breakup of the federation in 1992, the independence from the Soviet Union is still a marker of pride for many citizens of the post-Yugoslav countries. When challenged, people from the region will often go into passionate discussions to defend the uniqueness of the Yugoslav socialist experience, with its openness to the West, freedom to travel and work abroad, and a relatively high standard of living.

Some ex-Yugoslavs who have had the chance to visit the Soviet Bloc at that time will brag, with some degree of arrogance, that “we were like Americans to them!” They at times ignore the fact that some of those formerly downtrodden countries, like EU members Estonia and Poland, have made advances inconceivable in the modern-day Western Balkans.

The debate goes well beyond quarrels over coffee or beer. Passions flare up the highest when ex-Yugoslavs are put in the same basket as other Central and Eastern Europeans by political figures. A case in point was when UK Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt incorrectly characterized Slovenia as “a Soviet vassal state” during a visit to Ljubljana in February 2019, a gaffe that caused fierce reactions by the Slovene public, and beyond.

Yugoslavia was not behind the iron curtain. Yugoslavia was not behind the iron curtain. Yugoslavia was not behind the iron curtain. Yugoslavia was not behind the iron curtain. Yugoslavia was not behind the iron curtain. (repeat ad libitum) https://t.co/8RIYABloQV

— Tena Prelec (@tenaprelec) February 23, 2019

Similar online outbursts transpired when, in July 2017, the American journalist Joy Reid, who is considered left-leaning, mistakenly confused the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia while discussing the national origins of the wives of US President Donald Trump. Even though she tweeted a correction soon after, the fallout has lasted for years.

Yugoslavia was never a part of the Soviet Union, and during the Tito years very heavily opposed Soviet influence.

This is precisely why one needs to be by default skeptical of journalists and be changed of the skepticism solely on the merit of the veracity of arguments https://t.co/PrJotSOrsI

— sid (@SuspiciouslySid) March 28, 2019

In May 2018, a Business Insider article about a conspiracy theory that Melania Trump is a Russian spy misrepresented Slovenia's history, again drawing angry reactions:

Slovenia was a part of Yugoslavia until that country broke apart. Never a part of the Soviet Union or Russia. Where was the editor for this story? I trust the reporter has been fired for incompetence.

— Evan (@EvaninScotland) May 18, 2018

Another example occurred in sports journalism: in October 2018, an article on the history of Croatian-American soccer by the website Protagonist Soccer was quickly corrected after a reader alerted the publication that Croatia was never part of the Soviet Union:

Thank you for this piece on Croatian soccer. Please make one correction. Yugoslavia was not a “Soviet nation.” It was a communist state, but was never part of the Soviet Union. I would like to RT your article, but don't want the focus to be on this point. Many thanks.

— Luka Misetic (@MiseticLaw) October 26, 2018