On September 28, 2019, in Mexico City, feminist groups held a demonstration for the approval of the Olimpia Law, which penalizes with jail and fines the dissemination of erotic or sexual content without consent. Photograph by the author, CC-BY 3.0 [1].

In 2014, Olimpia Coral Melo Cruz [2], then 18 years old, recorded a sex video with her boyfriend. Days later, the video was shared online without her consent, and it was seen by her neighbors, acquaintances, relatives, and friends in her community of Huauchinango, in the state of Puebla, Mexico.

The activist told the BBC in Spanish [3] that everyone in her community was talking about her and the video. “Olimpia locked herself in her house for eight months and attempted suicide three times,” the website writes.

After going through a difficult depression, Olimpia regained her strength to stand up and defend her right to freely enjoy her sexuality. But when she decided to report the incident, the authorities said that there was no crime to prosecute, since there was no law or code that punishes digital violence against women.

For the last five years, with the support of feminist groups and organizations, Olimpia has been fighting to promote reforms to make the non-consensual dissemination of sexual or intimate content a punishable crime.

The initiative has become known as #LeyOlimpia [4] (#OlimpiaLaw) and has already been approved in 12 of the 32 states of Mexico, including Puebla. According to the Criminal Code [5] of this state, “it is punishable to disclose, distribute, publish or request without consent an image, whether printed, recorded or digital, with sexual erotic content of a partially or totally naked person.” The penalties range from three to six years in prison and a fine.

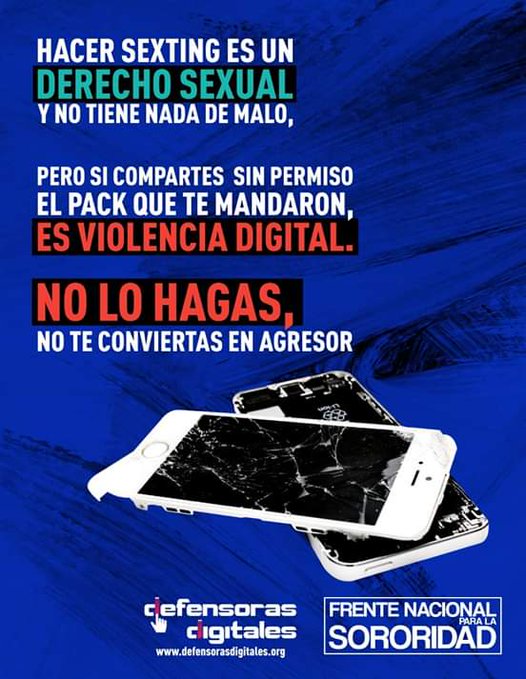

[6]

[6]The Facebook page [6] of the National Sorority Front has an information campaign on how women can be safe online.

A similar law is yet to be approved in Mexico City, but a bill has been submitted to the local Congress and the legislative process has begun. On September 28, activists and various organizations have taken to the streets in the capital to gather signatures in favor of the law. Over the past months, activists have also used the hashtag #LoVirtualEsReal [7] (“the virtual is real”) to talk about digital gender-based violence.

As spokeswoman for the National Sorority Front [8], Olimpia has traveled the country to promote the law that seeks to make visible the violence experienced by women in the virtual space. “They don't need to penetrate us in order to rape us through the digital spaces,” she said during her recent participation in the Legal March for the Legalization of Abortion, in the Zocalo square in Mexico City.

“No woman or girl who has been exhibited online wanted to be exposed like this,” she said.

Mensaje de @OlimpiaCMujer [9] durante marcha por #AbortoLegalParaTodoMexico [10] pic.twitter.com/HXXtTiwjov [11]

— Mrcds (@abraxas_m) September 29, 2019 [12]

Message from @OlimpiaCWoman during the #LegalAbortionForEveryoneMexico march

[13]

[13]Photograph from the Facebook page [13] of the National Sorority Front. Used with permission.

Although many survivors leave the digital space after being exposed, their physical environment, such as their school, family, and work, is also affected.

Finally, the Report on Online Violence against Women in Mexico [15] written by the Luchadoras.mx [16] collective warns that young women, aged 18 to 30, are the most vulnerable in digital spaces. However, the collective says that a detailed statistical record on the scale and characteristics of digital violence is still needed.