Africa silhouette image [1] by Natasha Sinegina (CC BY-SA 4.0). Visa page images [2] by Jon Evans (CC BY 2.0). Image remix by Georgia Popplewell.

In 2019, Temitayo Olofinlua [3], a Nigerian writer and academic, was denied a visa to attend the European Conference on African Studies [4] in Edinburgh, UK. The British High Commission in Nigeria said they were “not satisfied” that Olofinlua would leave the UK at the end of her trip.

The truth is: I am tired.

— Temitayo Olofinlua (@Tayowrites1) May 29, 2019 [5]

The visa refusal was later rescinded by the UK Home Office. Olofinlua went to the conference and has since returned to Nigeria.

Others have not been as lucky. In April 2019, the UK visa authorities prevented 24 out of 25 African scientists working on infectious diseases from joining their colleagues at various events taking place as part of the London School of Economics Africa Summit [6]. The people most invested in and best-positioned to tackle the problem of diseases on their continent, were barred from participating in an event about “the challenge of pandemic preparedness [7].”

The LSE will be holding its next Africa summit not in London but in Belgium due to the ease of securing visas for Africans there, and because so many African invitees now refuse to go through the humiliating British visa application process. https://t.co/Q3WfiHS7Ja [8]

— Mũthoni Mũrĩu (@jmmuriu) July 18, 2019 [9]

‘You won't come back!’

Barring Africans from entry into certain countries is not only humiliating — it also highlights the institutional racism [10] that underpins the notion that African professionals and creatives [11] cannot be trusted to obey the law.

Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [12] declares that “Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.” The reality, however, is that without a passport and valid visa, this right cannot easily be exercised. And the ease of getting a visa varies according to nationality. On the 2019 Henley Passport Index [13], Japan and Singapore hold the top spot for access to most countries, while Angola, Egypt and Haiti are at the bottom.

Kenyan author Ciku Kimeria describes the indignity of living without “passport privilege [14].” She notes that even a visa does not guarantee entry because “you still have to deal with the surly immigration official who will suspiciously ask, ‘And what are you here to do?’” If the answer to this question isn’t to the official’s satisfaction, visitors could find themselves being marched back to the departure gate.

We need to address this visa injustice. It’s time we talked about #visareciprocity [15]. If you apply these rules to Ugandans going abroad. Same rules should apply to foreigners visiting Uganda. Enough is enough. And Africa, it’s time to drop the visa requirements to visit each other pic.twitter.com/aiX0tsALSe [16]

— TMS Ruge (@tmsruge) July 11, 2019 [17]

For Africans traveling outside the continent, applying for a visa can feel like offering sacrifices to a ravenous god. Adéṣínà Ayẹni (Ọmọ Yoòbá), Global Voices Yoruba translation manager [18], recounts his recent experience trying to procure a visa to Lisbon, Portugal, for the 2019 Creative Commons Summit:

It was the greatest news of my life when I received a mail to deliver a keynote address at the 2019 CC Summit in Lisbon. . . . On April 18, 2019, some days to my birthday, I submitted my visa application to attend the Lisbon summit at the VFS Global office in Lekki, Lagos. The summit was slated for May 9-11, 2019, but visa processing takes a minimum 15 days.

On the day I was to depart for Portugal, I still [hadn’t] received my passport. . . . 11 days after the summit elapsed, I received a text from the VFS for collection of my passport. My people say, inú dídùn l’ó ń mú orí yá (you cannot be at your best when sad). It is one thing that I was not given a visa to attend the summit, another is that the huge scholarship grant to attend the summit went down the drain, wasted. I am miserable because I have not been able to refund the scholarship due to the Central Bank of Nigeria’s policy on wire transfers. It is excruciatingly painful that my right to associate as a free citizen of the global village was violated. I was stripped of my voice!

For Africans traveling within Africa: A painful irony

It’s difficult for Africans to travel outside Africa — but it can be equally grim [19] to travel within the continent. Citizens of many countries [20] in the global North can travel to most Africa countries visa-free, or with few restrictions [21], but the majority of Africans need visas [22] to travel to over half of the other African countries.

Nigerian Global Voices contributor Rosemary Ajayi [23] captures the “struggle of Africans traveling within Africa”:

I am happy that we, and many others, are highlighting the challenges Africans face getting Western visas. This doesn't annoy me as much as the struggles of Africans travelling within Africa. At RightsCon in Tunis, and GlobalFact in Cape Town, I took the time to ask Africans if they had needed visas. Just this weekend, I learnt of a Nigerian journalist who was unable to attend GlobalFact because he didn't have a visa. Let's not talk about how most of the African delegates at RightsCon had to fly out of Africa first, in order to get to Tunis. Last month, I met an East African journalist applying for a visa to Nigeria. He was asked to supply the driver's license of the professional driver picking him up from the airport!

As Rosemary points out, intra-continental travel is often further complicated by having to travel out of the continent in order to reach a destination within Africa.

At the International Air Transport Association (IATA) regional aviation forum in Accra in June, Ghana's Vice President, Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia lamented [24] the fact that “a business person from Freetown [Sierra Leone], for example, should travel for nearly two days to go to Banjul (often through a third country) for a journey which a straight-line flight would have taken only one hour.”

The convoluted flight routes are then compounded by the extraordinarily high cost [25] of air travel within the continent. The currency in the following tweet is Nigerian naira, around US$ 990.

I wanted to go to cote d’ivore last week, checked wakanow , the cheapest flight was 380k. Lagos to New York is 360k. https://t.co/ObJ5HfLFIF [26]

— ❤️ (@TounBash) September 17, 2018 [27]

Is it true that Africans are unlikely to return home?

[28]

[28]A rescue operation off the Canary Islands in 2006. Photo [28] by Noborder Network. (CC BY 2.0)

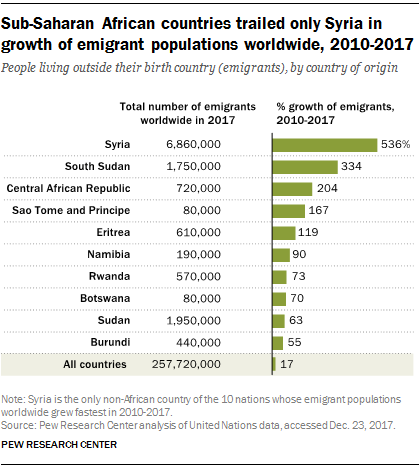

Between 2010-2017, migrants from sub-Saharan African countries accounted for the largest migrant population in the world after Syria. Many Africans leave the countries fleeing poverty or violent conflict, to seek asylum, refugee status or permanent residence [29] in North America or Europe. A 2018 Pew Research study reports that the number of migrants from sub-Saharan Africa “grew by [30] 50% or more between 2010 and 2017, significantly more than the 17% worldwide average increase for the same period.”

[31]Sub-Saharan Africans are also emigrating to countries far and wide. In 2014, over 170,000 migrants without legal documents ferried across the Mediterranean Sea to Italy [32]. Many hailed from sub-Saharan Africa. In December 2018, Brazilian police [33] rescued 25 sub-Saharan African nationals who had “been at sea for over a month” in the Atlantic Ocean. The travelers had paid “hundreds of dollars apiece” for the trip from Cape Verde. In June 2019, US Customs and Border Protection [34] in Del Rio, Texas, USA, arrested more than 500 Africans from Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Angola, for trying to cross into the USA via the Rio Grande River.

[31]Sub-Saharan Africans are also emigrating to countries far and wide. In 2014, over 170,000 migrants without legal documents ferried across the Mediterranean Sea to Italy [32]. Many hailed from sub-Saharan Africa. In December 2018, Brazilian police [33] rescued 25 sub-Saharan African nationals who had “been at sea for over a month” in the Atlantic Ocean. The travelers had paid “hundreds of dollars apiece” for the trip from Cape Verde. In June 2019, US Customs and Border Protection [34] in Del Rio, Texas, USA, arrested more than 500 Africans from Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Angola, for trying to cross into the USA via the Rio Grande River.

While dominant narratives in the media perpetuate Africa as a continent of mass migration driven by poverty or violent conflict, however, Marie-Laurence Flahaux and Hein De Haas, scholars from University of Oxford and University of Amsterdam, respectively, take issue with this stereotype [35].

Flahaux and De Haas argue that these narratives are propagated not only by “media and politicians” but also by scholars. Their research shows that migration from the continent is multi-layered and driven by global “processes of development and social transformation” that have increased the “capabilities and aspirations” of Africans’ to migrate — similar to migrants from other parts of the world.

These stereotypical narratives, however, often inform visa policy: Most countries’ authorities assume that all Africans who travel will not return to their home countries, leaving African visa applicants to bear the burden of proof.

Getting non-African nations to take a more nuanced approach to visa approvals for African nationals is a long battle. Meanwhile, African nations can take action to improve mobility across the continent. A common African passport is one step — but it's not enough. The Single African Air Transport market [36] (SAATM), and the Continental Free Trade Agreement [37], both launched last year, have laid the foundation for some of these shifts, but widespread implementation is still a long way off [38].

Meanwhile, as an African, to dare to travel is to be subjected to cruel humiliations when travelling outside Africa — or to be jolted out of the fantasy of African unity by the harshness of travelling within the continent. Either way the visa gods demand more sacrifices, while remaining adamantly intransigent.