In Kano, Nigeria, a boy rides a camel against the backdrop of NASA's space station, one of 18 Project Mercury space stations strategically placed along the Earth's orbital track. The stations were part of a vast global communication network necessary to track spacecraft and relay information back to Mercury Control Center at Cape Canaveral, Florida, USA. Picture released by NASA on May 21, 1962.

On July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 made world history when it landed on the moon. But to this day, few people know about the space stations in Kano, northern Nigeria, and Tunguu, Zanzibar, that helped lay the groundwork that ultimately made the Apollo 11 mission possible.

The Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States played out dramatically in the great space race. Before a successful moon landing could happen, the US needed to test manned and unmanned spacecraft. In October 1958, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) launched Project Mercury, a five-year, $400 million project designed to test the viability of human space travel.

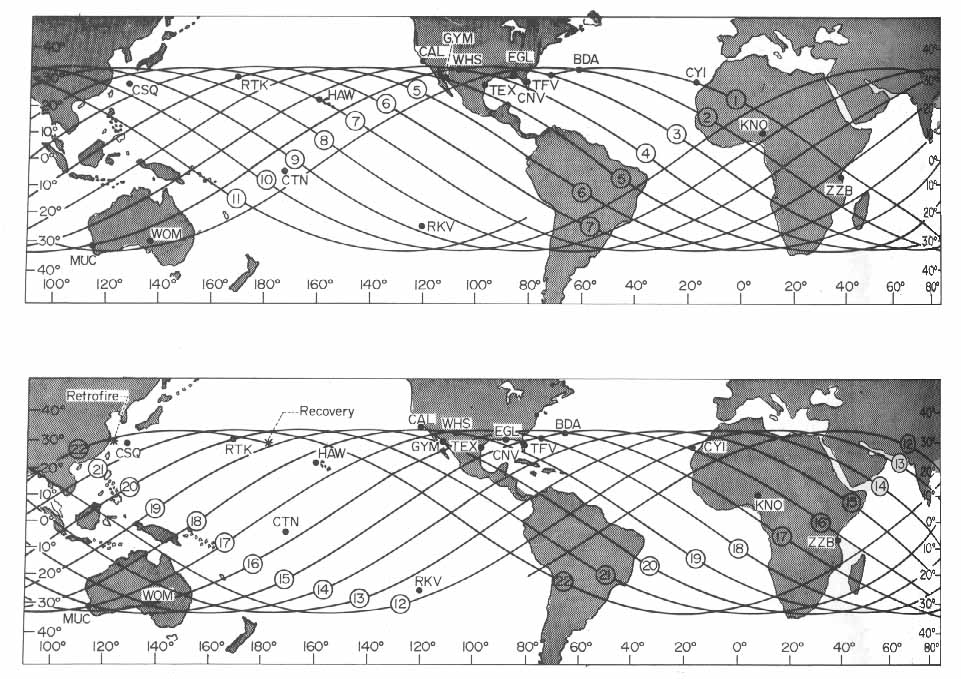

Launching a spacecraft into orbit required ground controls in countries located along the Earth’s orbital track. NASA built a total of 18 stations in strategic, global locations including Nigeria, newly independent from British rule, and Zanzibar, then governed by the Omani Sultanate along with a British administration.

Figure 8-1. Map showing the locations of the selected Mercury stations, NASA archival records.

Project Mercury vetted seven astronauts known as the “Mercury 7″ and ultimately completed several orbital flights in the early 1960s: 20 unmanned, including the Mercury-Atlas-4, two with chimpanzees onboard (“Ham” and “Enos”), and six manned orbits including MA-6 through MA-9) — proving that human space travel was possible.

In 1960, NASA constructed the satellite tracking space station in Tunguu, Zanzibar, just under 10 miles outside of Stone Town, the capital. The following year, they completed the last of 18 stations in Kano, Nigeria, each at an estimated cost of $3 million.

The British, along with then-Sultan Khalifa bin Harub, showed great support for the American space station and approved the sale of rural land in Tunguu for the project site in 1960.

Throughout the project, the US processed more than 1,000 tons of cargo through specially-designated US depots that organized shipments to Nigeria and Zanzibar, along with the other sites, including two on ships. Stations housed electronic equipment, cooling towers, water chillers, hydropneumatic tanks and diesel generators for power backup.

NASA Satellite Tracking Space Station, Tunguu, Zanzibar, 1961. Photo via the collection of Torrence Royer, used with permission.

NASA contracted with US and British engineers as well as local specialists and builders in Kano and Zanzibar, surveying the land to establish the most precise angles for radar antennae used to communicate with spacecraft as they passed above and below the horizon line, according to NASA historical records.

Kano, home to the ancient Kingdom of Kano, and Zanzibar, the hub of Indian Ocean trade for millennia, were now vital links in a global network to reach the stars.

World's first global communication network

Before there was the internet, there was Project Mercury. The race to space demanded that the world’s first global communication network have the ability to communicate between and among space stations, spacecraft and astronauts. The Mercury communications network included 102,000 miles of teletype lines, 60,000 miles of telephone lines, and 15,000 miles of high-speed data lines, according to NASA historical archives.

NASA equipped stations with “telemetry, tracking, and computation functions” as well as “flight control and monitoring” capabilities and “a multi-frequency air-to-ground reception and remoting provision.” An intercom system allowed several people to talk while others listened.

Communication between space station staff and the spacecraft was a highly orchestrated dance. After a spacecraft launched, 5 to 90 minutes would elapse before the vessel passed over a station, depending on the location. The Mercury Control Center at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, USA, would send a teletype message to stations with the time and coordinates, using data crunched from the spacecraft's passage over a prior station.

Figure 8-20. MA-9 orbital charts via NASA archival records.

Torrence Royer, an American whose stepfather, Roger Locke, worked at the Zanzibar space station and who spent a few years in Zanzibar as a young boy, writes:

The high-tech equipment, and the ‘reach-for-the-stars’ attitude’ intrigued many young Zanzibaris. I recall students in my school learning the schedules of the satellite launches and I remember young people would lay on the beach at night, on schedule, looking up, waiting for the spacecraft to pass overhead. One friend who had just heard about this phenomenon joined the beach-watchers … only to be somewhat disappointed by the small, slow-moving, star-like object that he witnessed. He expected a close fly-by of a ‘flying saucer’ perhaps.

Revolution — and change

Leading up to Zanzibar's 1961 general elections, doubts about the intentions of the US space station began to surface and a small resistance against its presence began to brew. Some feared Zanzibar could become a potential target for nuclear war.

In Zanzibar, graffiti shows a rooster (associated with the now-defunct Afro Shirazi Party) pushing an American cowboy (representing American imperialism) off the island, shouting “I have no need whatsoever [for you]! Get out of here!” in Swahili. Photo via the collection of Torrence Royer, used with permission.

Yet, the space station remained open, and on May 15, 1963, the final Mercury-Atlas 9 mission launched from Cape Canaveral, completing 22 Earth orbits lasting a harrowing 34 hours before landing in the Pacific Ocean, piloted by astronaut Gordon Cooper. The unprecedented success of this final mission essentially completed Project Mercury and set the stage for more ambitious projects like Gemini and, later that decade, Apollo.

That year, Zanzibar had a brief moment of independence when, in December 1963, the British left the islands as a constitutional monarchy under the Sultans of Oman.

But on January 12, 1964, a violent revolution in Zanzibar overthrew the Sultans, ending over two centuries of rule. When the dust settled, the new revolutionary government claimed the US-funded space station indeed posed a national security threat and demanded its removal.

Anti-Project Mercury protests on the streets of Stone Town, Zanzibar, April 12, 1964. Photo via the collection of Torrence Royer, used with permission.

On April 7, 1964, the US government announced that it would shutter the space station in Zanzibar upon the new Zanzibari government’s request. “We regret very much this necessity since the station was used strictly for peaceful purposes which would further man's scientific knowledge,” said NASA, adding they would look for new locations in East Africa along the Earth's orbital track. They settled on Madagascar.

After years under British and Arab influence, Zanzibar had begun to consider alliances with Chinese, East German and Soviet Union governments — and its socialist leanings became a diplomatic flash point. At the same time, newly independent mainland Tanganyika merged with Zanzibar in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania, with Zanzibar as a semi-autonomous region.

Today, the former space station is a rusted, graffiti-filled shell with no important markers to indicate its global role in the space race. But Zanzibar's spot along the Earth's orbital track means that star-gazers can still sneak peeks at the International Space Station as it passes over the island. The last sighting was on Tuesday, July 23, 5:11 a.m., and was visible for one minute.

The abandoned Project Mercury space station in Tunguu, Zanzibar, 2004. Photo via the collection of Torrence Royer, used with permission.

Kano space station remained open for two more years and closed in December 1966. But the Nigerian government went on to launch its own space program with satellites in space since 2003.

Nigeria plans to send an astronaut into space by 2030.