This post by Raisa Wickrematunge originally appeared on Groundviews, an award-winning citizen journalism website in Sri Lanka. An edited version is published below as part of a content-sharing agreement with Global Voices.

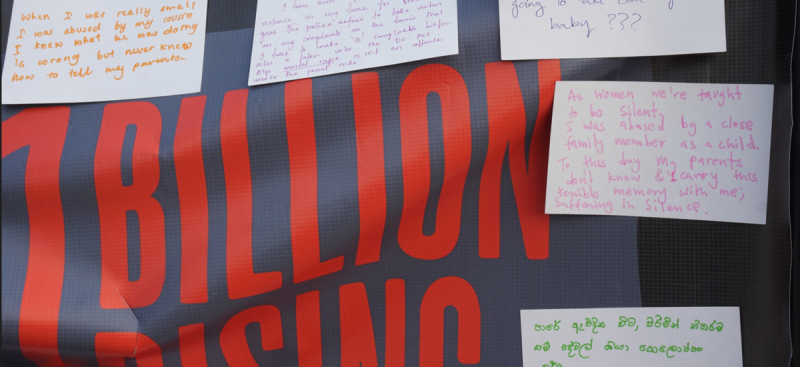

In recognition of International Women's Day 2016, Groundviews, a civic media initiative, mapped incidents of street harassment in Sri Lanka, none of which had been reported to the police. Those who contributed their stories to the map recounted experiences that remained painful or frightening, even years later.

For International Women's Day 2019, Groundviews tried to determine how much of a disparity there was between women's experiences of street harassment and available police statistics. While the grave crimes abstract, which is available on the Sri Lanka Police website, does have statistics on rape, statutory rape and sexual abuse, it does not specifically identify street harassment. In order to ascertain what statistics were available on street harassment for 2018, Groundviews filed information requests with both the Sri Lanka Police Headquarters and its Tourist Police division. Groundviews’ suspicion that the police did not record statistics for street harassment proved to be partially correct.

The map below (click here to view it more clearly) reflects available police statistics on sexual abuse: 2312 incidents of sexual abuse were reported in 2018, with 17 incidents of sexual abuse reported by tourists.

Both the Tourist Police and the Women and Child Abuse Prevention Bureau requested that Groundviews inspect the police logs. Providing the information would be logistically impossible, they said, since the officers in charge at both units would have to comb through an entire year’s worth of handwritten records. Their task would have been swifter and easier had the logbooks been digitized, but it appeared that the only nod to the 21st century was the grave crimes abstract itself, although its PDF format was not easily searchable, and it failed to define what the different categories mean (for instance, what qualifies as sexual abuse).

The data was also compiled differently in each division. The Women and Children’s Bureau was entirely unable to provide statistics for street harassment — in their data, this fell under the broad category of sexual abuse. Police Headquarters had a separate book logging the total number of sexual abuse cases reported for 2018 and this was what Groundviews received, though the officer on duty noted that it was not possible to get details about each reported incident.

On the other hand, the Tourist Police maintained their own logbooks, allowing them to provide a detailed, incident-by-incident breakdown that included cases of street harassment, flashing, sexual assault and rape. The officer in charge noted that tourists did not frequently complain of harassment — there were far more complaints of theft.

Yet, research shows that street harassment is common — and not just for tourists. A 2015 United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) study found that 90 per cent of women surveyed had experienced street harassment while taking public transportation. Of these incidents, 74 percent were physical in nature and included unwanted touching.

Complicating the issue is the fact that victims who do make police reports or come forward to talk about street harassment are often targeted themselves, particularly online. Responses to management executive Malki Opatha's tweet about her own experience of street harassment quickly turned into victim blaming, with many Twitter users asking her why she had chosen to sit near the window on the bus, and others telling her she should have shouted at the perpetrator.

18.12.18 #metoo

I was harassed on my way home.

I stood up from my seat near the window, I wanted to shout, I wanted to scream!

I couldn’t shout, I couldn’t scream, I was traumatized & my voice didn’t come out.

He got away!

It’s been 2 days now and it haunts me still ? #lka

— Malki (@MalkiOpatha) December 20, 2018

In response, Malki filmed a video explaining why she had not reacted to the person who harassed her: “We don’t react because we’re not ready. Even if we have an awareness about harassment on public transport, we don’t know how to react. We go numb. Our body freezes. Even if we want to shout, sometimes we can’t.”

Despite such powerful testimonies, a recent UNPFA campaign on street harassment, which coincided with the international campaign 16 Days of Activism against Gender-based Violence, still saw many commenters blaming those who came forward to share their stories, labeling it “attention-seeking”.

“With your make-up, he may [have] thought you were someone. I don’t like [women who put on] too much make-up. And another thing, why should he [harass] you? There aren’t any girls in bus except you??” one commenter said.

“He only asked [for] her phone number,” said another. “She didn’t know for what reason. I think it [could] be because he got her trust, he wanted to be friends. Think positively…is asking [for a] phone number from a girl also sexual harassment?”

Judging from the comments, many of the young men on the thread do not consider street harassment to be a serious issue. Nor do the police, it would appear. Although Groundviews’ aim was to map street harassment in a similar way to its 2016 mapping project, it was unable to do so, for reasons that go way beyond data collection.

While conducting research on technology-based violence, Groundviews was told during focus group discussions that the approach of the police and its Criminal Investigation Department often cause fresh trauma to victims who do attempt to receive some form of redress. It is not inconceivable that the same also applies to violence that happens offline.

At present, those who file complaints — including accusations of sexual abuse and violence — are met with a system for reporting such crimes that is neither designed for, nor responsive to their needs. Ongoing gender sensitisation programmes, comprehensive sexuality, and relationship education at the school level and the digitisation of police logs would be a good start in addressing these shortcomings.