[1]

[1]Zwarte Piet, Sinterklaas’ helping hand, is a fixture in the Netherlands’ St. Nicholas’ Day celebrations on December 6. PHOTO: Hans Pama (CC BY 2.0)

The first time I celebrated Sinterklaasdag – Saint Nicholas Day – with Dutch friends was when I was a student in New York. There were clever poems, riddles, gag gifts, and goofy customs. I was charmed. What a wonderful celebration it was.

What was missing from the celebration was Zwarte Piet [2] (Black Pete), Saint Nick’s blackface servant. That wouldn’t have gone down well in Brooklyn, and no one seemed to miss him. When I first saw Zwarte Piet in the Netherlands in 2002, I expressed outrage at the blackface figure throwing out candy to cheering crowds. I was immediately told that I was “too sensitive,” “too politically correct,” and “too American.”

“…there are jokes that cannot be made innocent…”

It turns out I wasn’t the first or the last American to be shocked by the minstrel figure. In 1944, Black American soldiers stationed in Limburg protested Zwarte Piet. The townspeople had to explain that it was all a joke. It wasn’t one that the soldiers found funny, according to the retelling of the incident in Geschiedenis van de Zwarte Piet-kritiek [3]by Jop Euwijk and Frank Rensen:

Men moest den protesteerenden [de zwarte Amerikaanse soldaten] duidelijk maken, dat Pietermanknecht een hoogst onschuldige grap is. Men moest Nederlanders uitleggen, dat er grapjes zijn, die anderen met den besten wil van de wereld niet onschuldig kunnen opvatten, hoe goed ook bedoeld.

They explained to the protesters [Black American soldiers] that the blackfaced Piet servants were all an innocent joke. In return, the Dutch were told that there are jokes that cannot be made innocent, no matter how good the intentions.

“If you want to understand the Netherlands, look at who has the right to demonstrate.”

![Naomi Pieter: "If you want to understand the Netherlands, look at who has the right to demonstrate. Nazis, Pegida [right wing political group from Germany]…Instead of blocking Nazis, you block people struggling for inclusive societies. We receive threats of violence from the right and the police shut down our march and let the Nazis march. They give them the whole stage.”](https://globalvoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/naomi-1-800x400.png)

In recent years, the protest against Zwarte Piet has taken on a renewed urgency. People have taken to the streets. In 2016, around 200 people were arrested, most of them black. Activists have been the targets of harassment and death threats. Artist and activist Naomi Pieter describes that day as one of the most traumatic of her life:

The police surrounded us, they caged us. And then they pulled black people into our circle, even those who were not part of our group. That’s what happened to Jerry [Jerry King Luther Afriyie]. He wasn’t part of our group…First they [the police] singled him out. He was standing across the street. Then they loaded him onto the arrest bus. Then they pulled him out. Then they beat him…It was the most traumatic experience of my life.…

If you want to understand the Netherlands, look at who has the right to demonstrate. Nazis, Pegida [right wing political group from Germany]…Instead of blocking Nazis, you block people struggling for inclusive societies. We receive threats of violence from the right and the police shut down our march and let the Nazis march. They give them the whole stage.

This image compares the image of Jim Crow with the image of Zwarte Piet. The translated text is from a 1945 article in a Dutch newspaper.

“The silly Dutch with their quaint customs”

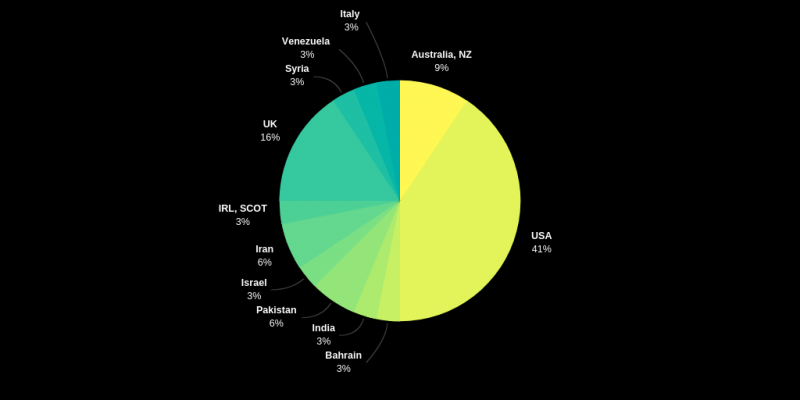

For this article, I talked to over thirty people non-native residents of the Netherlands about their first impressions of Zwarte Piet, and how those impressions have changed. Like most of the respondents, Karl Webster was “freaked out and confused” the first time he came across Zwarte Piet. Many people couldn’t believe their eyes, describing it as a dream, a mirage, silly, and racist. Others described being horrified and angry.

Respondents came primarily from English speaking countries.

Here's a selection of the responses.

Shawna Snow:

Our first experience was coming outside seeing the parade of when Saint Nicholas coming to Spain. I was with my five kids and my mother-in-law and we had no idea what was going on. We’re walking around going, what is going on. And then we see these white people in black faces throwing cookies with this really pious and sad looking Santa Claus on this white horse. And they’re screaming and the cookies are flying, and I’m thinking: this would never fly in the States…

“My mom was an antique collector, so I recognized the blackface, the mammy faces, from turn of the century [early 1900s] Vaudeville, and I knew this was a really racist presentation.

Anne-Marie Roche was confused the first time she saw Zwarte Piet in Amsterdam:

I was taking my baby daughter to creche on one of the coldest mornings I have ever experienced in Amsterdam and I spotted some people who appeared to have painted their faces black running around with sacks. It felt more like a strange dream. A few years later I attended my first Sinterklaas intocht [welcoming ceremony] and realised it was not a dream. This really happened in Holland.

A 25-year-old respondent discussed her discomfort with a tradition she first came across as a child:

I couldn't understand why white people, especially adults, would purposefully paint themselves fully black with exaggerated red lips, wear big afros, and then pretend that this happened to the piets going down the chimney (while sinterklaas was white as can be), who prior to that were fully white people with blond hair. I recall white kids (and through their silence, white parents) wickedly “joking around” that Black and Brown classmates were piets who should stick to helping (read serving) and picking up after Sint (read white people).

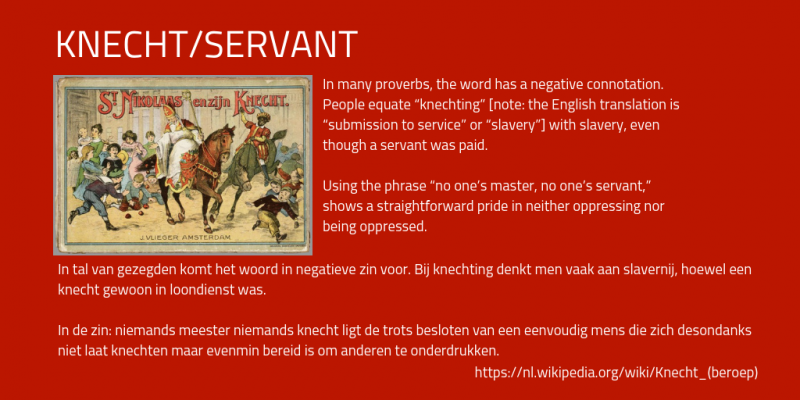

Zwarte Piet is often described as a servant, in Dutch a “knecht”

“Get rid of racist nostalgia that does not fit our modern time.”

Like many of the other respondents, Faten Bushehri’s partner is Dutch. The first time she saw Zwarte Piet cookies for sale, she announced her intention to boycott the bakery.

I had a good conversation with my Dutch fiance about it, and he also heard many other perspectives of some of my friends. I heard the Dutch arguments about preserving culture and traditions, and my response was, if your tradition is to be racist you should change your tradition. Children don't care whether Piet is black or green or white, they are not going to miss it. Get rid of racist nostalgia that does not fit our modern time.

Lara sees the whole thing as “nothing more than when seeing Santa's elves. A cultural phenomenon. I have to say I heard about the whole debate before Sinterklaas.”

And a 66-year-old respondent first came across the tradition in 1985:

I first saw Zwarte Piet thru the eyes of 3-year-old twins, so a naive sense of wonder and joy overrode my own thoughts. However, I’d heard a story about how he beat bad children with sticks and whisked them off to Spain in a sack. This created an unsettling ambivalence. Foreshadowing?

Now he wonders how those twins present the Sinterklaas tradition to their own children.

A 37-year-old respondent remembered the first time he saw the Zwarte Piet figures:

I thought it was a racist stereotype. I'm from the US (Texas) and the first time I saw a Piet was in Utrecht, in the centrum [center]. There were a few Pieten hanging in the window of a shop and because I had never heard of this I actually stood outside the show for ten minutes waiting for someone to react to what I thought was a reference to lynching and blackface.

“I don't want my kids to accept something so toxic as normal”

Several of the respondents considered the impact on their own children or future children. Chris Saxe’s children are growing up in two cultures: the US and the Netherlands:

Maybe because I have children now, but I’m even more aware of its continued – and more muscular – prevalence. I don't want my kids to accept something so toxic as normal – and not just because my children have their feet in two cultures (USA & NL). That there are lots of white Dutch willing to defend Zwarte Piet with the arguments (“Heritage! Tradition!”), vitriol, and suppression of dissent that the American South uses to defend the Confederate flag and statuary comes as no surprise at all.

Holly echoes Chris’s point:

My child went to a Dutch school when we first arrived in the country and he came home confused and we had to undo that damage – seeing blackface being normalised… I am so disappointed that there is any one arguing to retain this ritualistic humiliation of people of colour. I'm angry enough that my kids have been exposed to stereotypical images and black caricatures but then I speak to black friends whose children are hurt by this every year, and my having to undo damage to my (white) children is nothing to what they put up with. I'm also appalled at the police brutality wrought on protesters last year, that's not the country to which I thought I was moving. And then after all this, seeing the willful denial and ignorance of those defending Zwarte Piet is a horror show of white privilege in action. It's a huge scar on the character of my adopted country.

Faten says, “If this holiday is about glorifying colonialism and slavery, then we should rethink the whole thing.” She wonders why not use a different character altogether? Why not a rabbit?

My partner is Dutch, I’m going to make sure my kids don’t participate in this phenomena, I’m not going to send them black man cookies. I’m not going to dress them up as Zwarte Piet.

Isn’t this a time of joy and inclusiveness? For some kids this is the most stressful time of the year. That’s not fun.

“The vibrancy and dynamism of any culture are reflected in its capacity for inclusivity”

Many defend Zwarte Piet with the comment, “Think of the kids.” Tammy Sheldon reminds us that children won’t notice if the tradition is changed:

Kids have a supple imagination; the fun will not be lost. I mean, K3 (the very popular children’s pop group) has changed its lineup several times over the years, with no harm done to its fans. I mention this as the constant refrain of objection is “think of the kids!” Obviously, different folks have different rationales for not changing. At the end of the day however, what is being asked is on every level reasonable, and does not take away from a kid’s party, nor from the foundational culture of a society. The vibrancy and dynamism of any culture are reflected in its capacity for inclusivity.

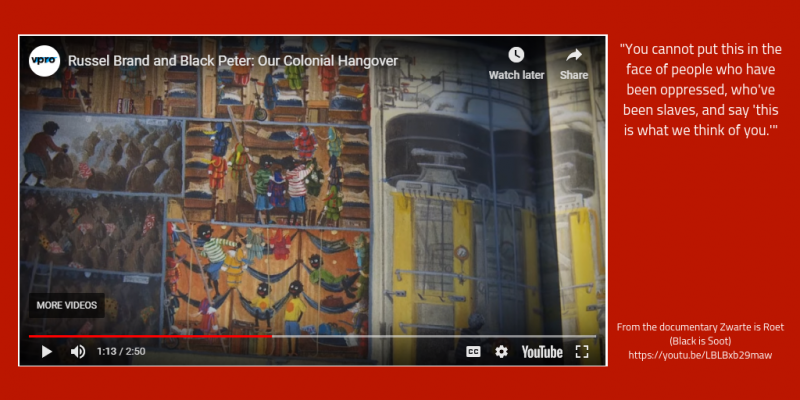

Screenshot from the documentary Zwarte is Roet (Black is Soot) [4] by Sunny Bergman.

“It's a huge scar on the character of my adopted country.”

An Australian respondent states:

After the Dutch were told repeatedly that this was a racist caricature some rethought the story. I loved the multi colored piets that came into being — but many Dutch complained at the loss of their heritage and persisted with Blackface Piet and sooty Piet. That means I can no longer think they are casual racists who don’t know better. Now I know that they put their racist childhood fantasy traditions ahead of respect and empathy. And I am ashamed of myself if I go into a shop with a Piet doll. It’s awful.

Elena studied nationalism and invented traditions and saw the arguments for keeping Zwarte Piet as “a classical case-study of constructed identity, that at the beginning I could simply not justify such a short-sighted position as those looking at Zwarte Piet as a non-negotiable trait of their being.”

She adds:

Then I explained it to my parents, who are politically engaged and highly educated people, and they said: ‘aren’t you exaggerating? It's just a tradition’. That made me think of when I had first come to the Netherlands and not given attention at first to its real meaning. Compassion for me and them and everyone else, you can say. And I got the idea we need to talk more with each other, listening to each other’s stories, in order to go beyond a pointless polarisation.”

A 56-year old woman from the UK describes it as “a harmless, very nice tradition that is being turned into a racial question by some people with a political agenda.”

A respondent originally from San Francisco writes:

As an American, I find the blackface tradition tone deaf to the horrors of Dutch colonialism (slavery). Yet everyone around me, both native Dutch and Dutch people with immigrant backgrounds, all love Black Pete.

“… implicit in his appearance and his duties to Saint Nik is the historical unjust treatment and exploitation of people of colour”

Like many, Eric Asp’s first response was one of shock. Over time he developed a more nuanced understanding:

I think I developed a deeper understanding for how most Dutch people experience the various festivities surrounding Sinterklaas and all the warm memories they attach to their traditions (including Zwarte Piet) — but the American side of me always recognized an element of racism with Zwarte Piet, and I learned to more gently push back against that particular tradition.

Ben Falkenmire agrees:

“I understand Dutch affection for Zwarte Piet is born out of a warm, and well-meaning Christmas tradition. But I cannot excuse it. The very sight of Zwarte Piet I still find offensive because implicit in his appearance and his duties to Saint Nik is the historical unjust treatment and exploitation of people of colour.”

The last word goes to the activist Jerry King Luther Afriyie from an interview with the Dutch newspaper Het Parool [5]:

De intocht. Wat is daarmee? Als je nu nog aankomt met Zwarte Piet, ben je zelf de demonstrant. Dan wil je ons kennelijk duidelijk maken dat zwarte mensen hier niet thuishoren.

The welcoming ceremony? Well, what of it? If you still come as Black Pete, then you are the demonstrator. You are letting us know that black people don’t belong here.